The Visual System

On the necessity of a sparse code

Let us consider (after Graham, 2005), a collection of 5 by 5 images,

representing the alphabet. The first 4 letters are shown below. Over 4

millions symbols (2^25 divided by 8 (4 orientations and 2 exact inverse))

can be represented by a combination of those 25 black or

white pixels. It sounds a little bit of an overkill for only 26 letters,

so we could restrain ourselves to a 4*2 matrix, but it makes the picture easier. The

idea is that whenever a letter is represented, the white pixels on its

representation will be 'ON'. If we consider that A, B, C and D have an equal

probability of occurence, each pixel is ON 56% of the time. If we had a

dedicated template for each letter, it would be ON only 1/26th i.e., less

than 4% of the time. From an energetic perspective, the later

representation sounds more appealing. Indeed, a low firing rate seems to agree

with the neuronal metabolism.

Figure 1:

A, B, C and D represented by 5*5 arrays.

Field and Olshausen's experiment

When modelling a neural network, training stands for development and/or evolution. In the model

Field and Olshausen proposed (Olshausen, 1996), the learning algorithm

aimed at maximizing sparseness of the code used to represent natural

images, while still accurately representing them. In short, the cost

function to minimize had a first term accounting for the accuracy of the

representation (mean square error between the original and the

reconstruction) and a second term measuring sparsity (a non linear

function of the coefficients of the representation telling how the

energy is spread among the basis vectors). The first term assumes that

the brain aims at giving us as much information as it can, the second

term assumes that it is energy-limited.

They found a family of localized, oriented, bandpass components, which look very

much like wavelets.

Figure 2:

Principal components calculated on 8*8 image patches extracted from

natural scenes (From Olshausen, 1996).

Natural scenes

Is it a surprising result? By itself maybe not: we know that natural images are

sparse in a DCT or a wavelet basis for example. This is what allows

compression. For the natural scene below (original on the left), if we

take its DCT transform and throw away 88% of the coefficients (the

smallest ones), we

can reconstruct the image almost perfectly (reconstructed image on the right).

More fundamentally, the concept of a best basis has been introduced (Mallat, 1999), which could

provide more insight, but it was beyond the scope of this project.

Figure 3:

Example of a naturel scene before (left) and after (right) transformation.

88% of the coefficients of the DCT have been

discarded.

Receptive Fields

What was exciting about Olshausen's results though was the fact that such

a basis of oriented, localized and bandpass components look very much like

the set of receptive fields cells that are found at several levels in the

retina and in the visual cortex.

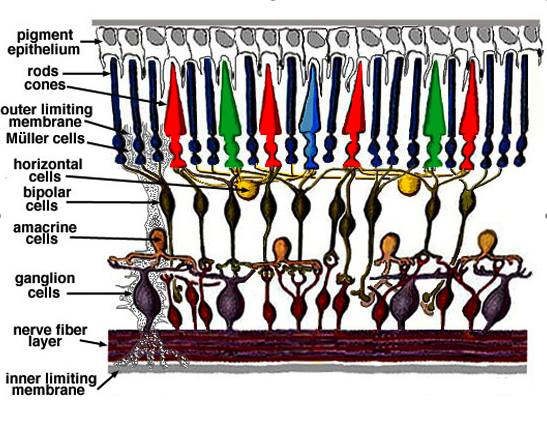

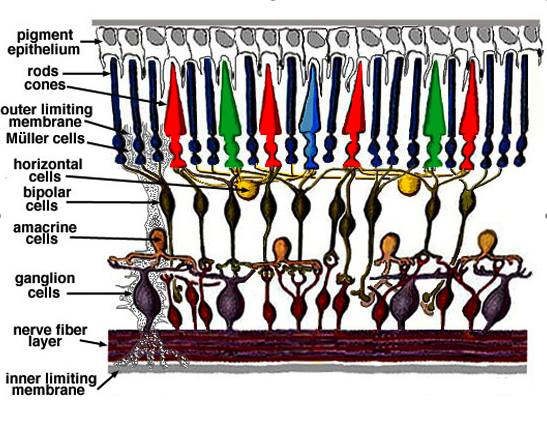

In the retina, the

receptive field of a given bipolar cell is the circumscribed area of the retina this cell is

getting input from.

The photoreceptors absorb light and signal this information through the release

of the neurotransmitter glutamate to bipolar cells, which in turn transfer information to

ganglion cells. Bipolar cells have receptive fields with center-surround inhibition. The

center is produced through direct innervation of the photoreceptors above

it, either through metabotropic (ON) or ionotropic (OFF) receptors.

The surround requires some processing. It probably happens through the

horizontal cells. Those have synapses on both, cones in the center of some

bipolar cell's receptive field and cones in the surround of some

other bipolar cell's receptive field. The exact mechanism involved is

not yet known (Kandell, 2001).

Receptive fields of cells in the visual cortex can be classified

into simple or complex cells depending on the

stimulus triggering them (Hubel, 1959; Hubel, 1968). Orientation (stimulus in

some specific orientation) and/or

direction (stimulus moving in some specific direction) selectivities are important properties of those receptive

fields. Therefore, the definition of the receptive field of a cell needs to be

extended: it is no more the region of space where the presence of a stimulus will

trigger the cell (which for bipolar cells corresponds to the area on the

retina the cell is getting input from), but this region plus an

orientation.

Figure 4:

Organization of the retina (From

http://webvision.med.utah.edu/sretina.html). Light enters at the

bottom.

Random dot kitten

It is very tempting to conclude that the brain

through development and/or evolution has shaped the receptive fields cells in

order to provide us with an accurate and energy-efficient representation of the

world we live in.

However, one could also argue that it works the other way: since we have

receptive fields cells, the world being what it is, we get a sparse

representation of it.

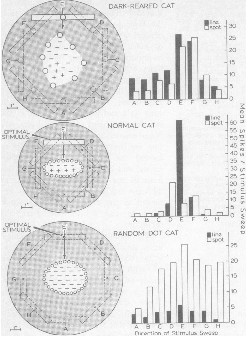

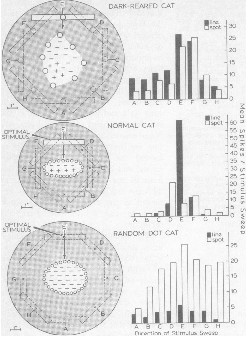

Pettigrew (Pettigrew, 1973) showed that kitten reared in the dark and exposed

to a planetarium-like environment deprived of lines and edges

developped receptive-field cells sensitive to spots of lights and not to

edges as a kitten reared in a normal environment would do.

This experiment strengthens our very tempting conclusion above.

Figure 5:

Comparison of typical neurons from the striate cortex

of cats raised under three conditions: (i) total absence of

visual stimulation, (ii) normal visual experience, (iii) visual

experience confined to randomly arranged light spots (From Pettigrew, 73).

As a sidenote, Berkeley

(among others)

would have probably been thrilled by those results.