Single-Pixel Imaging

The single-pixel camera developped at Rice University is an example of how

compressive sensing allows us to move from a "Digital Signal Processing" (DSP)

paradigm to a "Computational Signal Processing" (CSP)

paradigm (Takhar, 2006). In this new paradigm, analog signals are no longer sampled

periodically, but they are converted to a new representation, on which

further processing is based.

Apart from being an example of compressive sensing, such a single-pixel camera

is also arguably useful when

the detector is expensive and N-pixel arrays cannot be

built. Time-multiplexing a single detector is then a cost-effective

solution. For example, silicon is blind in the infrared, so CCD and CMOS

technologies cannot be used. A classical camera in the infrared is hundred times

more expensive than a digital camera for the visible (Duarte,

2008).

Hardware

Digital Micromirror Device (DMD) were used. The DMD consists of an array (1024*768) of

electrostatically actuated micro-mirrors. Each mirror can be positioned

in one of two states (+/- 12 degrees). Light will be collected by the

subsequent lens if the mirror is in the +12 degrees state.

As a sidenote, DMD Discovery 1100 by Texas Instrument costs $6000 in the visible, $6700 in the

near infrared, and $8700 in the ultra-violet.The accessory light

modulator package (ALP) was used, which costs $7650. So this infrared

camera costs already more than $15000 (http://www.dlinnovations.com/).

The DMD could be replaced by a MEMS-based shutter array placed direclty

over the photodiode (Takhar 06).

Figure 1:

Single-pixel camera block diagram (From http://www.dsp.ece.rice.edu/cscamera/)

Analysis

Using a modified Walsh basis extends the dynamic range D (required

for each single pixel of an N pixel array) to ND/2 since each Walsh basis

test function has N/2 entries with value 1 (Duarte, 2008). So much

light per measurement reduces dark current. However,if a smaller dynamic

range is desirable, it seems that a sparse basis could be used (Berinde,

2008). The trade-off between dark

current and dynamic range will determine the appropriate

sparsity. random_sp.m can be used to generate such bases.

The quantization error scales with the dynamic range. log(D'/D) additional bits

are required to keep the same error. If D'=ND/2, and N = 256, it makes 8

additional bits. If D' = 8N ( with the 8-sparse basis proposed above),

it makes 3 additional bits.

The photon counting noise (Poisson noise) depends on the chosen basis (i.e. how many photons are

wasted). The error due to Poisson noise will be affected by the

reconstruction method (Duarte, 2008).

Simulations

Below are some real images acquired with the single-pixel camera. More images can be

found here. Imperfections of the system contribute to additive noise in the obtained images: subtle

nonlinearities in the photodiode, nonuniformity of the mirrors

(reflectance and position), quantization noise at the A/D convertor,

circuit noise in the photodiode. The reconstruction should alleviate

quantization noise and circuit noise.

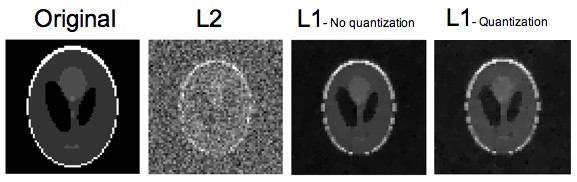

Figure 2:

Picture from a 'normal' digital camera (Left). Picture from the

single-pixel camera (Middle K=800 measurements, Right K=1600, the

reconstructed images have 64*64=4096 pixels).

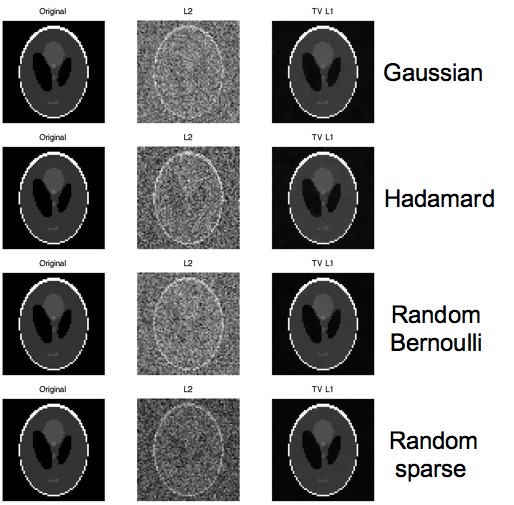

We performed simulations of compressive sensing, first in an

optics-free case and then using the digital camera simulator ISET. Outside of the DMD which we believe was this one, none of the optical properties of the single-pixel camera were available. We took the following numbers: for the first lens f (focal length) 0.08m, F number 4; for the second lens f 0.1m, F number 4; the photodiode is a single 2.8um*2.8um pixel with integration time 0.101s and geometric efficiency 85% (which does not matter that much since there is a single pixel); we assumed monochromatic light, illuminance 90 cd/m2, and 12 bit digitization. Losses at the DMD were not simulated. For all simulations below, we took K=1024 measurements of a 64 by 64 Shepp-Logan phantom

(N=4096). Note that the reconstruction will work better as N becomes

bigger.

For the optics-free simulations, we looked at different measurement

matrices.We got almost perfect reconstructions with all of them.

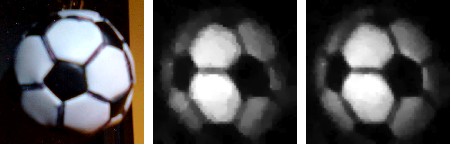

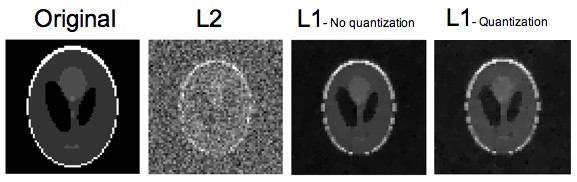

Figure 3:

Optics-free simulations with different measurement matrices. The l2

norm (least squares) performs poorly in all cases. The l1 norm

minimization gives almost perfect reconstruction.

For the optics-limited simulations, we used the Hadamard-Walsh basis as measurement basis and adapted the dynamic

range accordingly. As mentioned above, alternative solutions could be found. The digitization is implemented

in a simple way which does not take the effective range of the signal

into account. Empirically, it has been found not to be a limiting

factor (Duarte, 2008). As in the optics-free case, the l1 reconstruction

outperforms by far the l2 reconstruction. However, the reconstruction is

not perfect anymore, as expected.

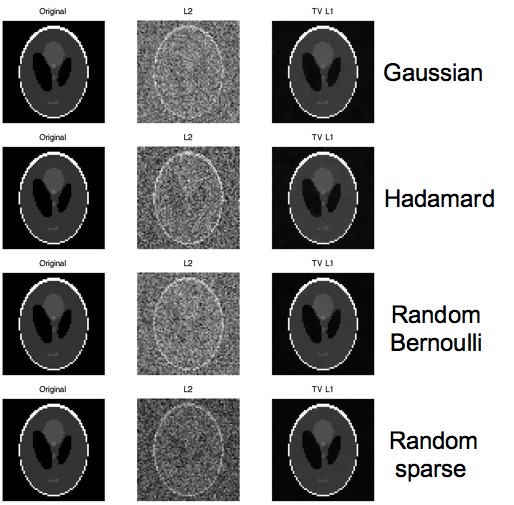

Figure 4:

Optics-limitics simulations with and without quantization. The l1

minimization reconstruction is much better than the least squares

reconstruction, but the phantom is not perfectly reconstructed anymore

because of the blur introduced by the two lenses.

In (Duarte, 2008) a Daubechies-4 wavelet basis is used for the sparse

reconstruction (i.e., as basis where the signal is known to be sparse). However, cscamera_test.m provided here is using the mesurement

matrix directly, so we believe that the original signal was assumed to

be sparse, without the need to do any transformation. We used the same

assumption in our simulations. We also tried to used the Fourier basis as sparse

basis (since the Shepp Logan phantom has a sparse Fourier

representation) but did not get good reconstruction so far (even in

the ideal case, without the optics), probably

because of the parameters used and the bad conditioning of the matrices. cscamera_test.m

is using a total variation minimization with quadratic constraints,

whereas we used a total variation minimization with equality

constraints and slightly different parameters. Our goal was not to

reproduce their results (since none of the optics was known anyway),

but to get an idea of the relative contribution of the reconstruction

and the optics to the imperfections seen. We have provided a framework

in which further, more precise simulations, could be performed.