Index | Introduction | Methods | Results | Conclusions | References and Acknowledgements | Appendix |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction

Color vision deficiencies are the inability of a certain person to see differences in color that is visible to other people.

Causes of Color Vision Deficiencies

While there are a variety of causes for colorblindness, including brain damage or chemical exposure, the most frequent cause of colorblindness is genetic.

Mutations in the genes encoding different wavelength photoreceptors can make them less sensitive than the receptors in the population norm, reducing the color vision capabilities in the individual with the mutation. Since red and green photoreceptors are encoded on the X chromosome, color vision deficiencies often sex linked.

Only one normal copy of the gene recoding the receptor is necessary for normal color vision; therefore, males, who have only one copy of the X chromosome, are much more likely to be color deficient than females, who have two copies of the X chromosome, and therefore have a better chance of having an un-mutated copy of the gene.

Types and Prevalence of Color Vision Deficiencies

There are three major types of color blindness; they are anomalous trichromacy, dichromacy, and monochromacy, in decreasing order of occurrence.

People with anamalous trichromacy have all 3 wavelength receptors – short, medium, and long – but one of the three receptors has mutated and does not absorb light of that wavelength as efficiently as an un-mutated receptor. When the mutated receptor is the long wavelength (red) receptor, this condition is known as protanomaly. When the mutated receptor is the medium wavelength (green) receptor, this condition is known as deuteranomaly. Finally, when the mutated receptor is the short wavelength (blue) receptor, the condition is known as tritanomaly.

People with dichromacy are missing an entire receptor type all together. When the missing receptor is the long wavelength (red) receptors, this condition is known as protanopia. For missing medium (green) wavelength receptors, it is known as deuteranopia. Finally, for missing short (blue) wavelength receptors, it is known as tritanopia.

There is a finally type of color blindness, monochromacy, which is the total inability to distinguish any colors. This condition, however, is extremely rare.

The prevalence of the different types of color blindness in both males and females are summarized below:

Confusion Lines

A common misconception is that color deficiencies affect only the vision of certain colors. For example, many people think that “red-green colorblindness” only affects the visibility of red and green colors. This, of course, is a misconception.

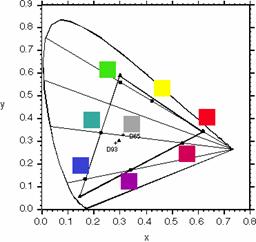

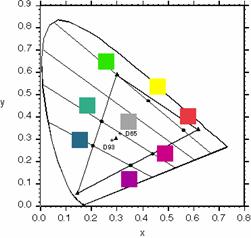

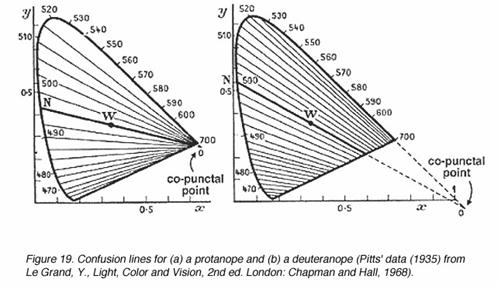

Confusion lines provide a better way to understand color deficiencies. Confusion lines are lines on the CIE xy chromaticity diagram where a person with a color deficiency will have trouble telling different colors apart. They are straight lines originating from a certain co-punctual point, the coordinates of which depend on the type of color deficiency, and extend radially out.

Here is another view of the confusion lines, this time with the co-punctual points marked:

Source:[1] http://webvision.med.utah.edu/KallColor.html

The exact coordinates for the co-punctual point are: • Protanope: ( 0.7465 , 0.2535 ) • Deuteranope: ( 1.40 , -0.40 ) • Tritanope: ( 0.1748 , 0 ) Source:[3] V.C. Smith, J. Pokorny; Spectral sensitivity of the foveal cone photopigments between 400 and 500 nm; Vision Res.(15) 1975; 161-171.

The Ishihara Test and its Problem

Due to the widespread prevalence of color deficiencies in the population and the importance of correct color vision for some professions, there has always been a need for a test to see whether someone has normal color vision.

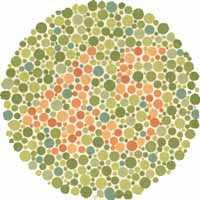

An Ishihara plate; people with normal color vision should see a 25 on a calibrated display.

The traditional color vision test is the Ishihara test, invented by Shinobu Ishihara in the 1910s. The test is composed of a number of different plates, each of which has a series of seemingly random dots. In the most common type of plate, a foreground and background color difference forms a number, and the colors were picked along a confusion line. The difference was visible to people with normal color vision, and a number can be read out by them, but the difference was not visible to people with the color deficiency along that confusion line, and the number was not readable.

However, there is a big limitation with the Ishihara test. Since the Ishihara test is a test with a fixed set of plates, it is a binary test. If you pass a certain number of plates (usually 15 out of 16), you pass the test. Otherwise, you fail. The Ishihara test can’t distinguish variances in color vision abilities among individuals in the population other than dividing them into two groups: normal and abnormal vision. But logic dictates that, even within the normal color vision group, there will be variations in color vision capabilities. So how should the population be tested for this variation?

Source: [4] http://www.cleareyeclinic.com/ishihara.html

A New Method

In this project, I developed a software system which, when used on a calibrated monitor, can test for individual variations in color vision abilities, even among people with self-reported normal color vision. How? Read on.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||