Critical Flicker Fusion Distance

PSYCH 221 Final Project

By Sheila Bijoor (sbijoor) and Daniel Golden (dgolden1)

Introduction and Motivation

The human visual system interprets information from visible light in the

environment by periodically sampling images projected onto the retina. The

sampled information is then integrated by the visual system to form complex

decisions about whether an image is stable or moving. In some cases, however,

the periodicity in which the eye samples leads to limitations in its

responsiveness to change. When intermittent stimuli are presented, the visual

system's perception of whether the stimuli are separate, flickering, or "fused"

(i.e., multiple stimuli appearing as a single static stimulus) depends on

multiple factors. These factors include (1) luminance, or brightness, of the

stimuli (Hart Jr, WM 1987), (2) chromaticity, or color irrespective of

brightness, of the stimuli (Kelly 1974), (3) frequency at which the stimuli are

alternated (Truss 1955), (4) the retinal position of stimuli, or whether it

excites rods or cones (Tyler and Hamer 1990), (5) size of stimuli (Hecht and

Smith 1965), and others.

In this project, we investigate the effect of color contrast on the eye's

ability to identify flickering images. We wish to determine:

(1) the critical chromaticity and luminance distance between the a base and

alternate stimuli before which alternations between the base and alternate are

seen as fused. We call this distance the Critical Flicker Fusion Distance

(CFFD).

(2) how the CFFD depends on the particular subject characteristic of Red-Green

color-blindness.

We compare our results to previous work on this subject by Truss in 1955, in

which he measured the chromatic flicker fusion frequency (CFFF) as a function of

the chromaticity and luminance difference between pairs of colors presented

alternately.

Experiment Methodology

Equipment

To administer our experiment, we used the Psych Toolbox

(http://psychtoolbox.org), a set of third-party scripts for Matlab. The Psych

Toolbox uses specially compiled code in order to interface directly to the

computer's video card, while avoiding Matlab overhead. This allows for very

precise timing when performing vision-related psychophysical experiments.

However, because of the complexity required for this interface into the video

hardware, the Psych Toolbox is initially fairly difficult to install and work

with; we probably spent as much time attempting to install the bloody thing as

we did working with it.

Past experiments have shown that the refresh rate of typical LCD monitors (60-85

Hz) is often at or below the human threshold for flicker fusion. LCD monitors

typically have lower refresh rates than what modern video cards can support

because of their slow "response times," i.e., the time it takes for a pixel to

completely change from black to white and back again. Thus, we decided that LCD

monitors - despite their prevalence in our office, where the tests were

administered - would not be suitable for our test. Instead, we selected a

lonely, neglected CRT monitor (a KDS "VisualSensations" piece) that had been

sitting on the corner of Sheila's desk, collecting dust, since her matriculation

into our research group. Although the monitor was somewhat dim (indicating a

smaller-than-usual gamut), it did allow for refresh rates up to 120 Hz (not true

for many other CRTs that we tested). Therefore, this lonely pauper of a monitor

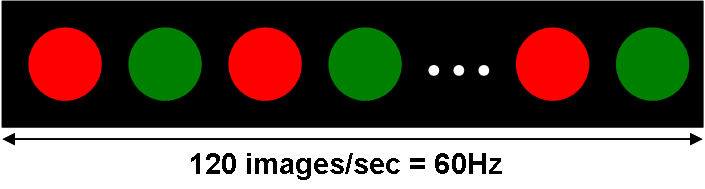

quickly became the prince of our psychophysical experiment. Note that a refresh

rate of 120 Hz allows for a maximum flicker frequency of 60 Hz (see below

image).

Initially, we intended for our experiment to traverse multiple flicker

frequencies and Base/End color pairs. However, during our initial testing

of the experiment, we determined that any flicker frequencies below 60 Hz (e.g.,

30, 20, 15 Hz) were too easy to perceive, and therefore not useful for our

experiment. Thus, our experiment was conducted using only the 60 Hz flicker

frequency.

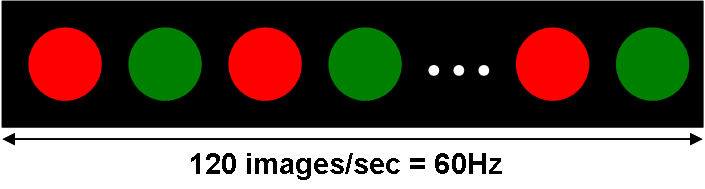

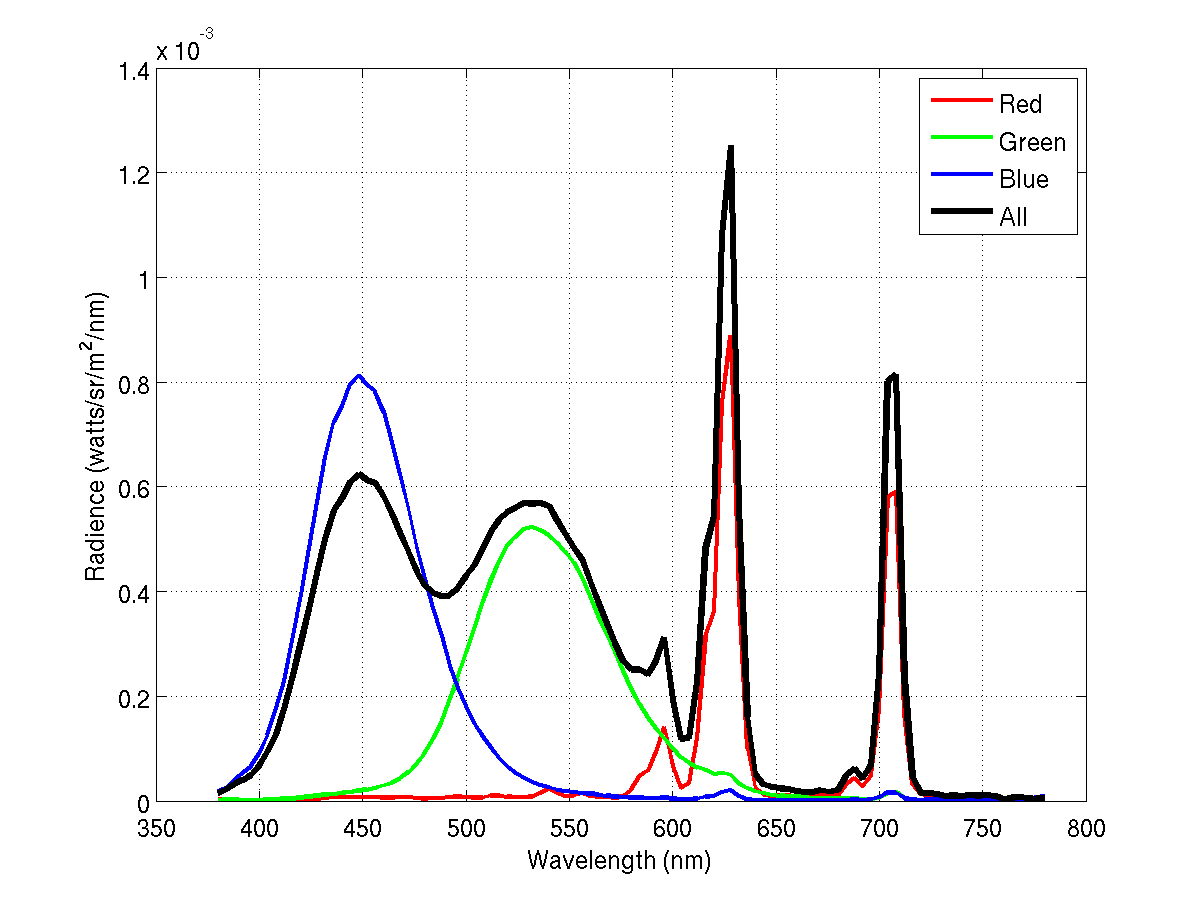

We calibrated the VisualSensations monitor using a PR650 spectral photometer

measurement device and the Dmtoolbox Matlab code provided by the Stanford

Vision, Imaging Science and Technology Activities (VISTA) laboratory at

Stanford. The calibration procedure consisted of activating the monitor

phosphors in different linear combinations and measuring the resulting spectral

power distribution (SPD) of the display (below). This calibration data was

useful in our experiment to convert from absolute color spaces, such as CIE LAB

and XYZ to the proper values to input into the VisualSensations's RGB

framebuffer.

SPDs from calibration of KDS VisualSensations CRT monitor.

SPDs from calibration of KDS VisualSensations CRT monitor.

Experimental Procedure

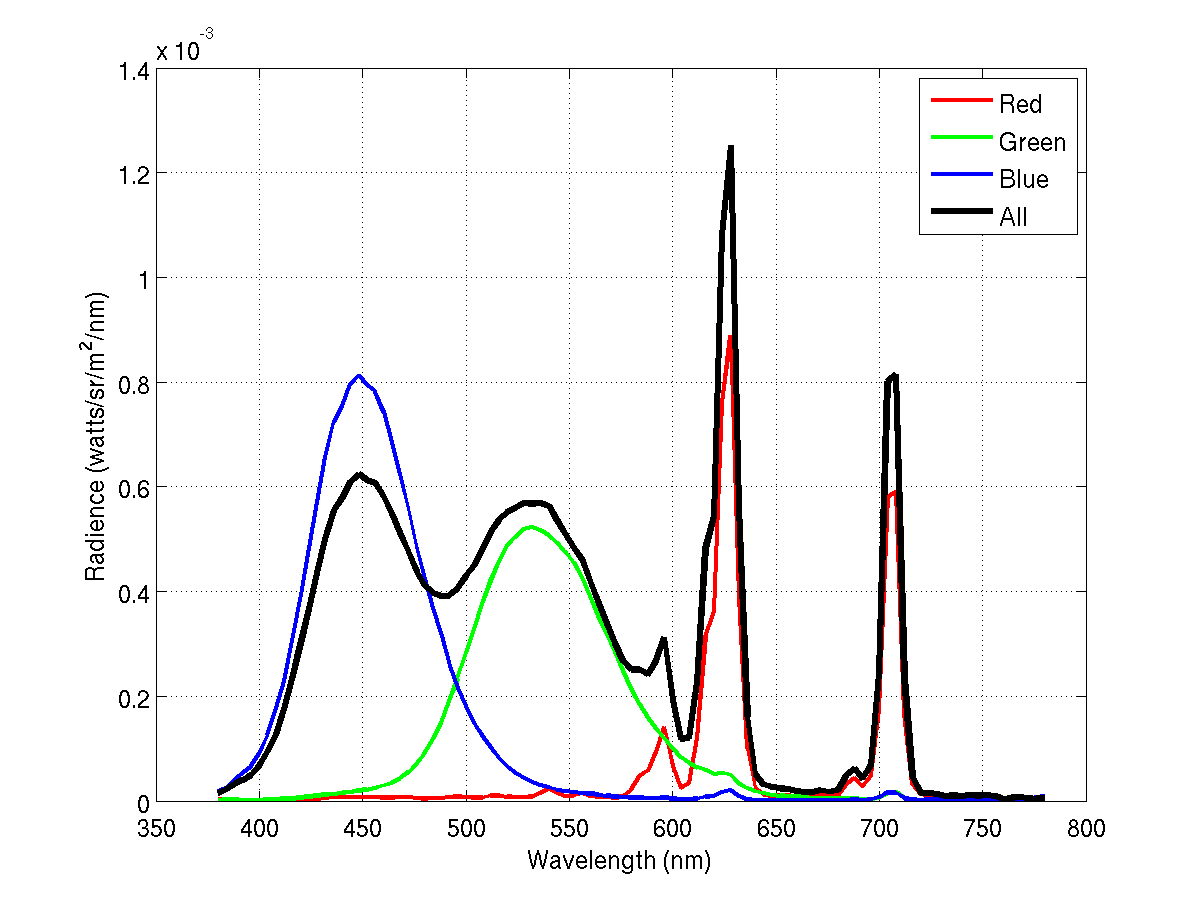

Our experimental procedure was a follows. The user was shown two stimuli in

random order: (1) two collocated circles of color, flickering at 60 Hz, and (2)

the geometric mean in CIELAB space of those two colors (it was later pointed out

to us that the color that would better approximate the "mean" of the flickering

colors would have been the geometric mean in RGB space -- oops). The user was

then asked to select which of the two stimuli was the flickering one: either the

first, or the second.

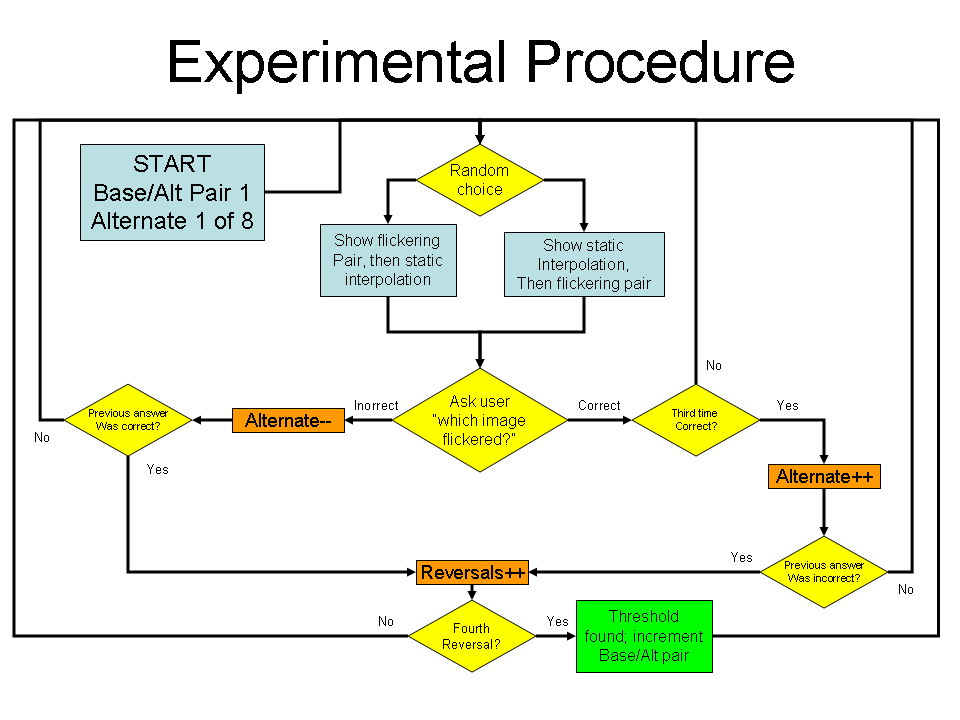

We implemented a "staircase" procedure in our threshold detection. Beginning at

the "top" of the staircase (a Base/Alternate color pair for which the two colors

are distant from each other, for which flickering is easy to detect), the

subject may advance one step down on the staircase whenever they correctly

identify the flickering pair three times in a row. One step down on the

staircase corresponds to a Base/Alternate color pair that is closer together in

the CIELAB Euclidean norm sense (i.e., for which flickering is more difficult to

discern). If the user incorrectly identifies the flickering pair, they

immediately advance one step up on the staircase, bringing them to a

Base/Alternate color pair that is further apart in CIELAB space (i.e., for which

flickering is easier to discern). Every time the subject switches direction on

the staircase, this is known as a "reversal." The trial with any given Base/End

pair ends when either the subject has undergone four reversals, or has reached

the bottom of the staircase (which, in each case, corresponds to the eighth

Base/Alternate pair). The full experimental procedure is summarized below.

Flowchart for Experimental Staircase Procedure

Flowchart for Experimental Staircase Procedure

Color Choices

We chose six different Base/End color pairs for this experiment. A Base/End

color pair consists of the "Base" color and eight "Alternate" colors. The first

Alternate color is the "End" color, and there are seven linearly interpolated

colors (in CIELAB space) in between the Base and End colors. The staircase

begins by flickering the Base and End colors; each movement down the staircase

corresponds to flickering the same Base, and the next closer Alternate color to

the Base.

In addition to the three possible RGB Base/End color pairs, namely Red/Green,

Green/Blue and Red/Blue, we also used Black/White, Purple/Yellow and

Orange/Green. These Base/End pairs are summarized in the below table.

Base/End Pair

|

RGB Coordinates

|

Max CIELAB Euclidean Distance

|

Red/Green

|

[1 0 0]/[0 1 0]

|

25

|

Green/Blue

|

[0 1 0]/[0 0 1]

|

35

|

Red/Blue

|

[1 0 0]/[0 0 1]

|

20

|

White/Black

|

[1 1 1]/[0 0 0]

|

35

|

Purple/Yellow

|

[0.5 0 1]/[1 1 0]

|

40

|

Orange/Green

|

[1 0.5 0]/[0 1 0]

|

15

|

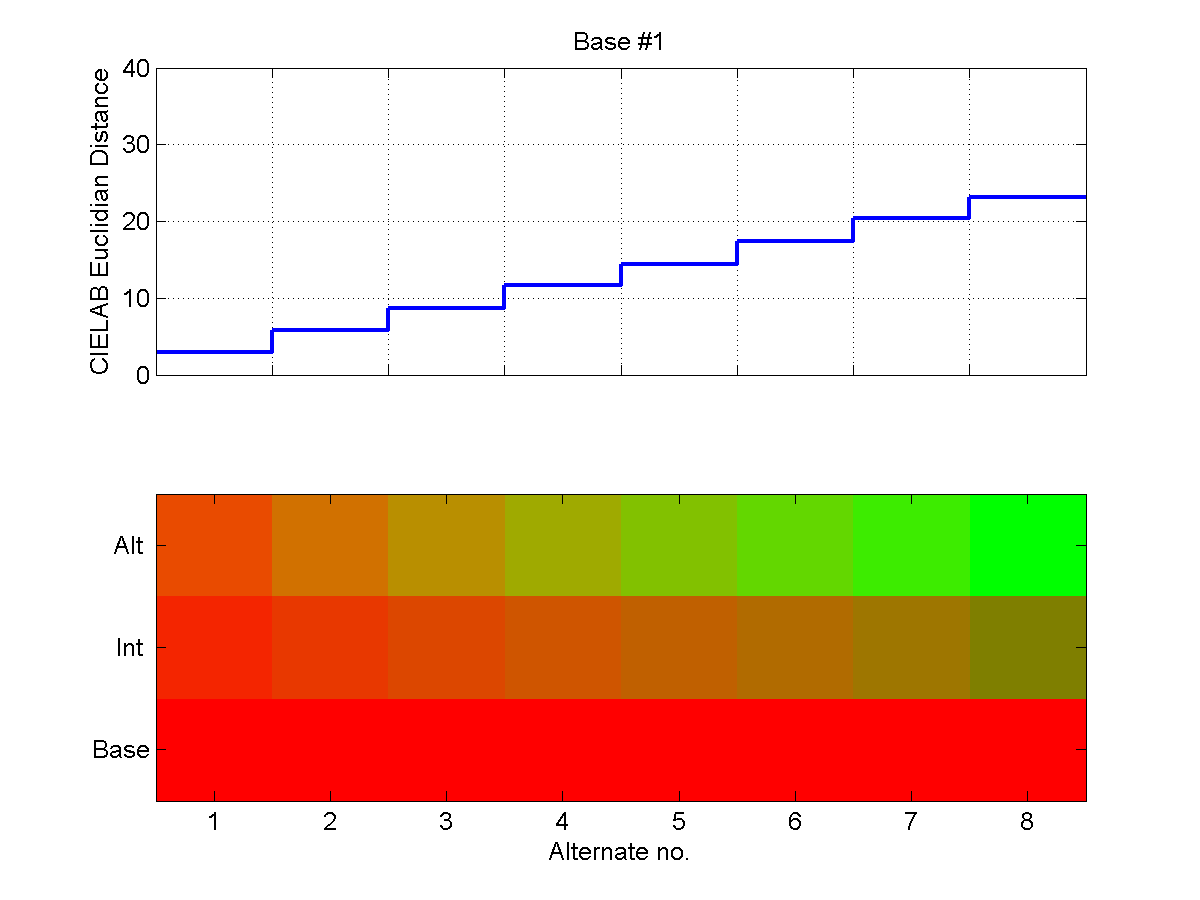

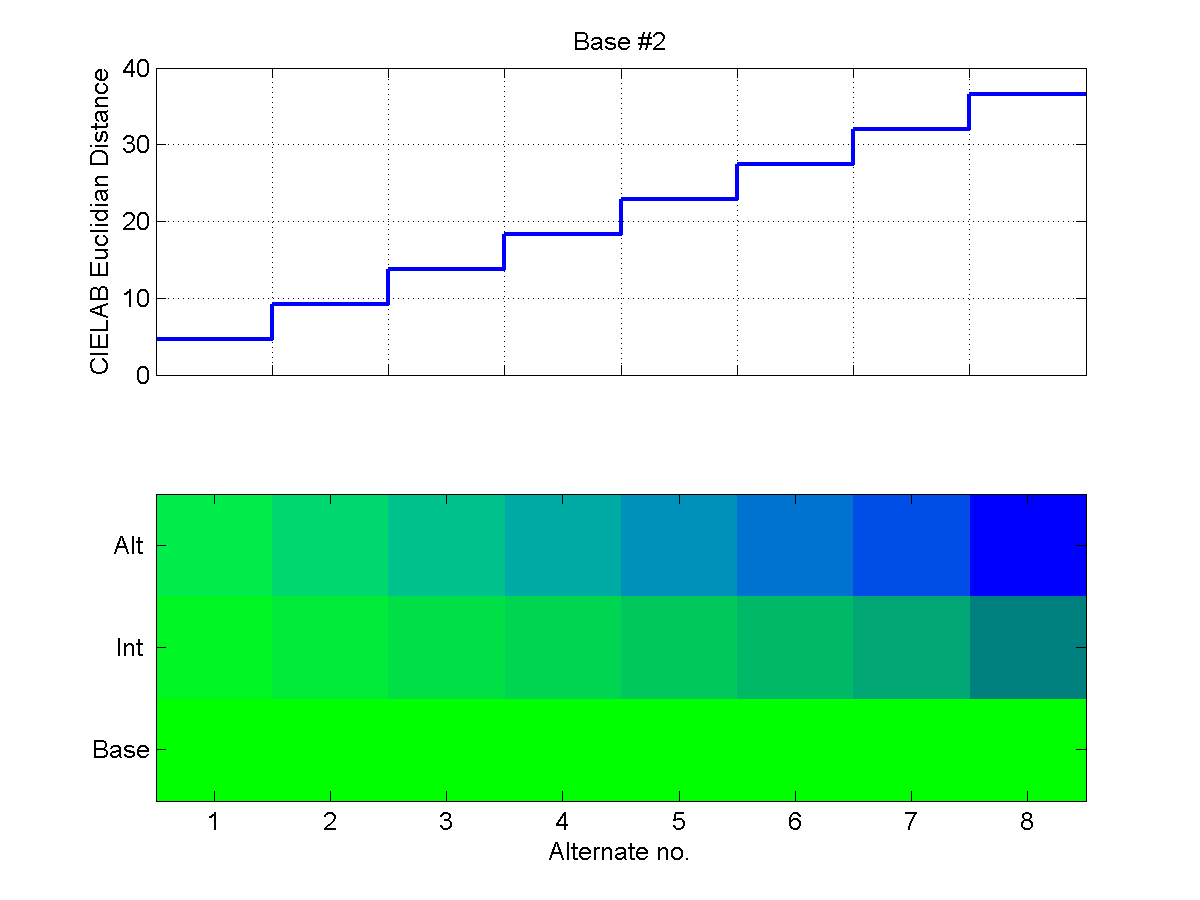

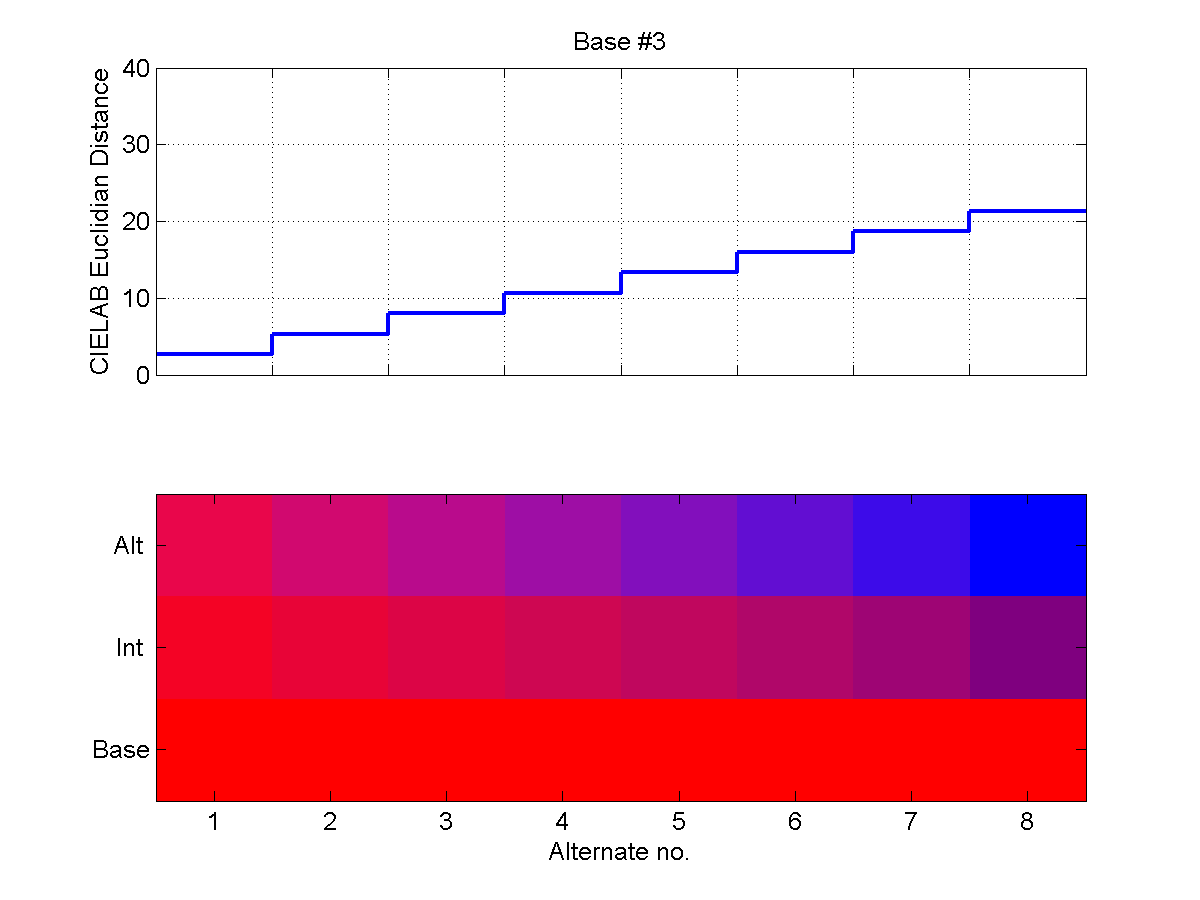

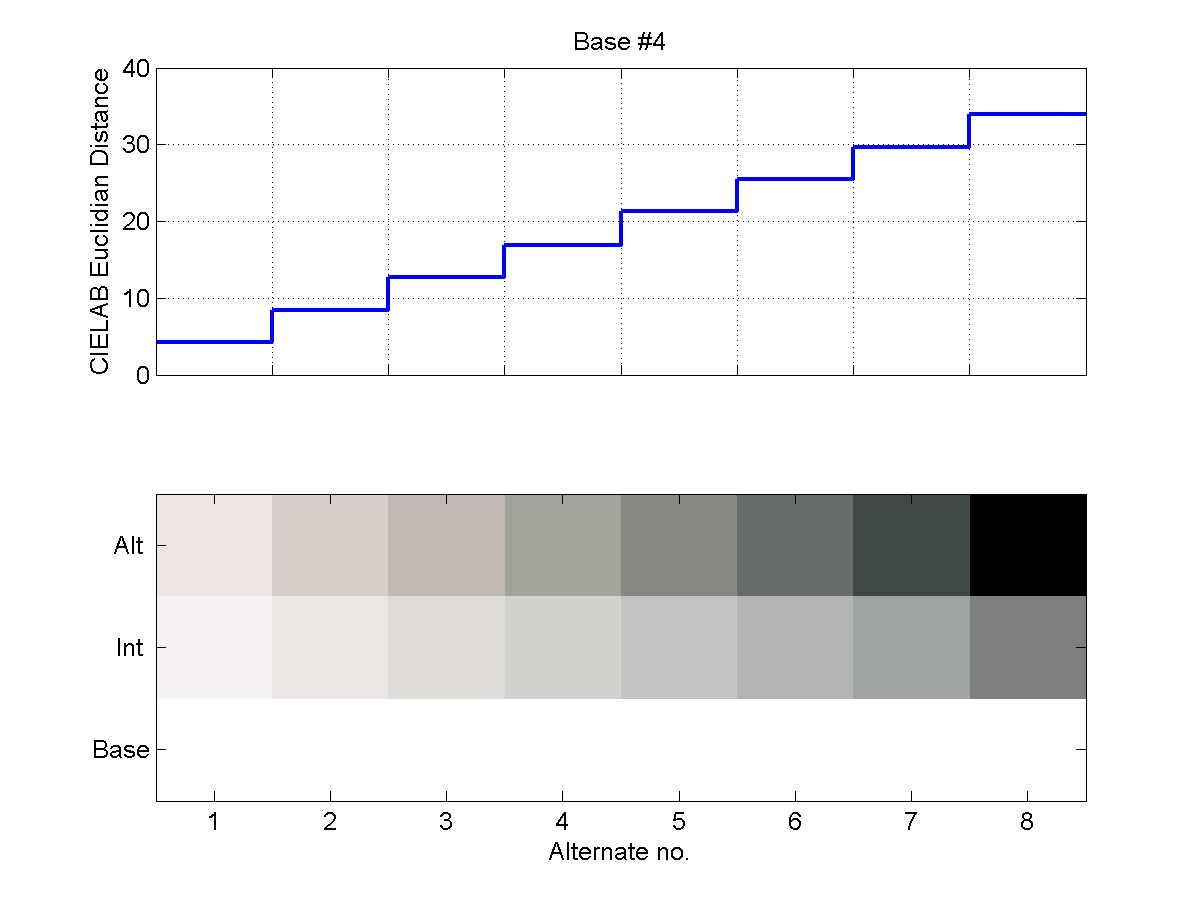

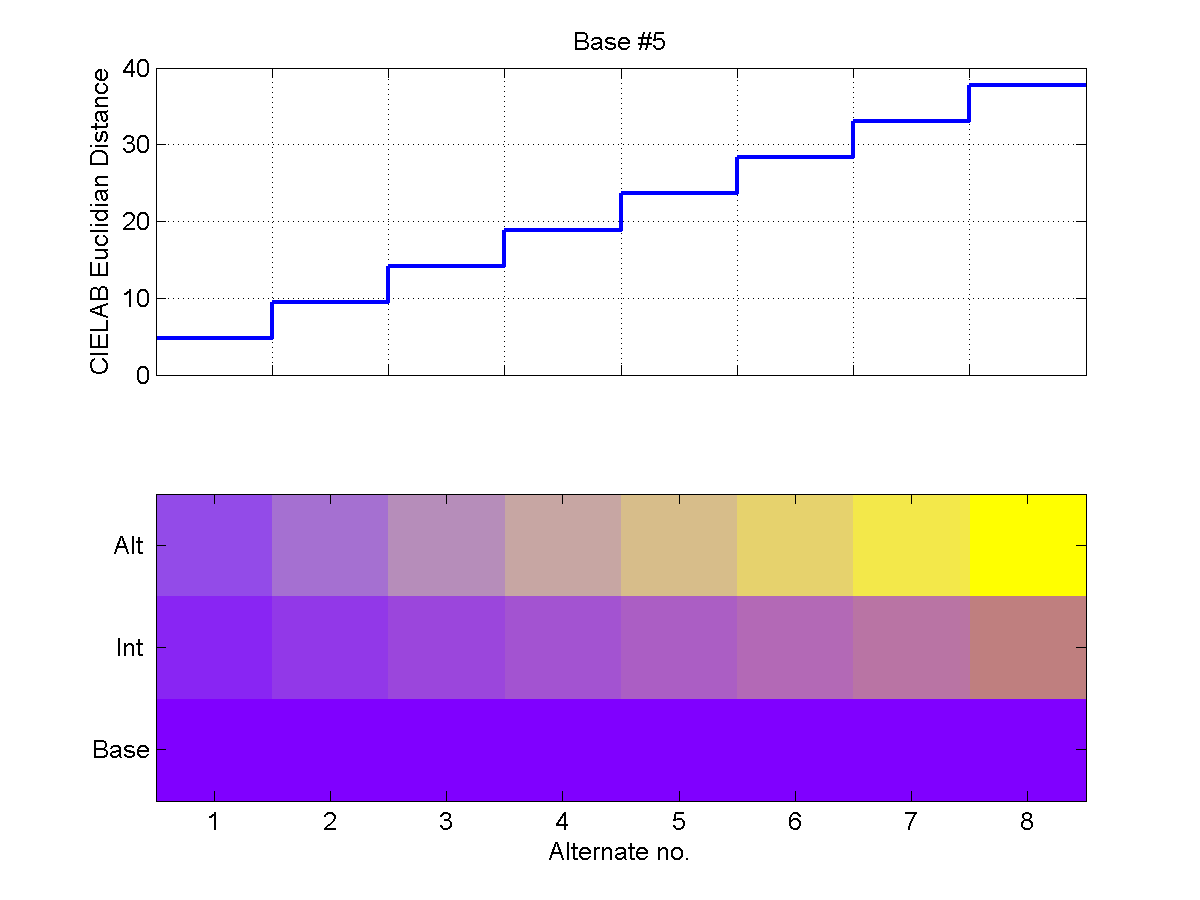

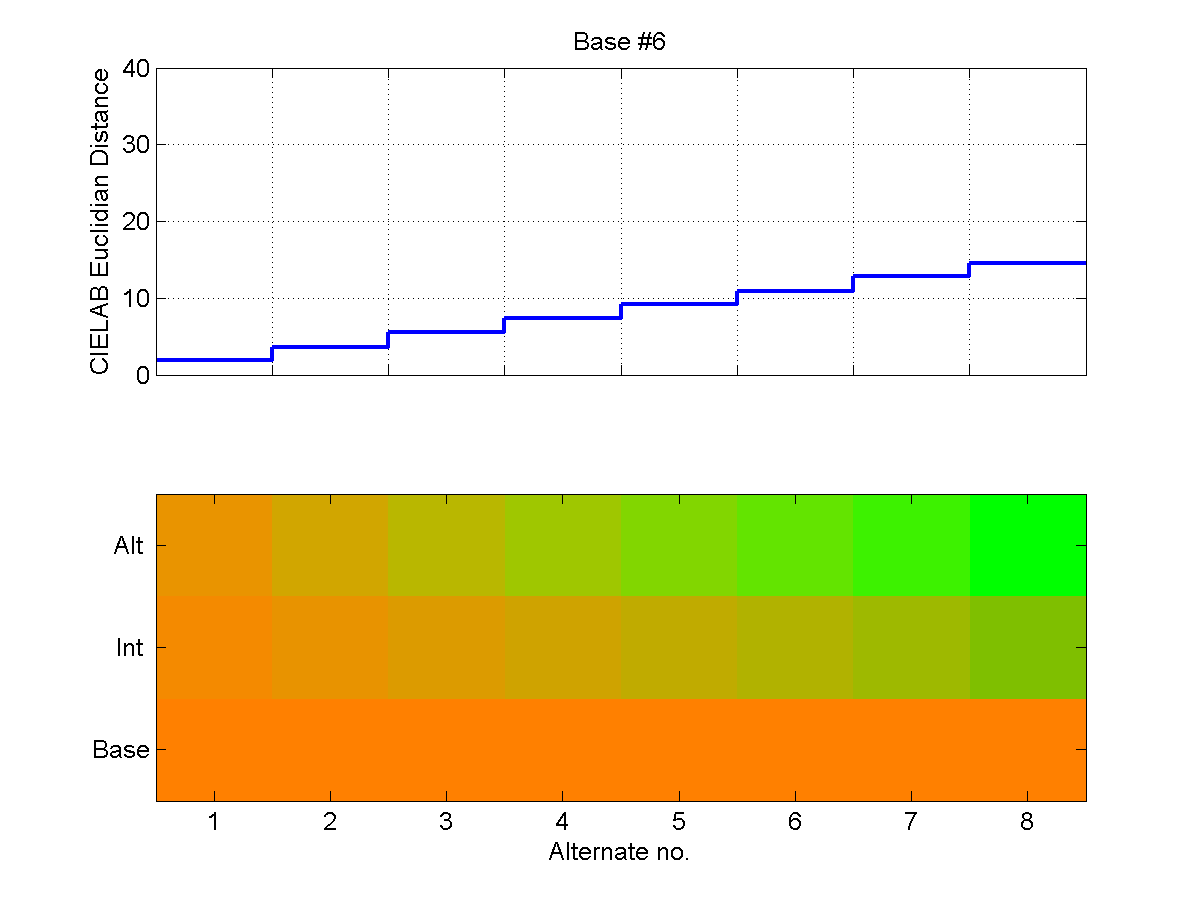

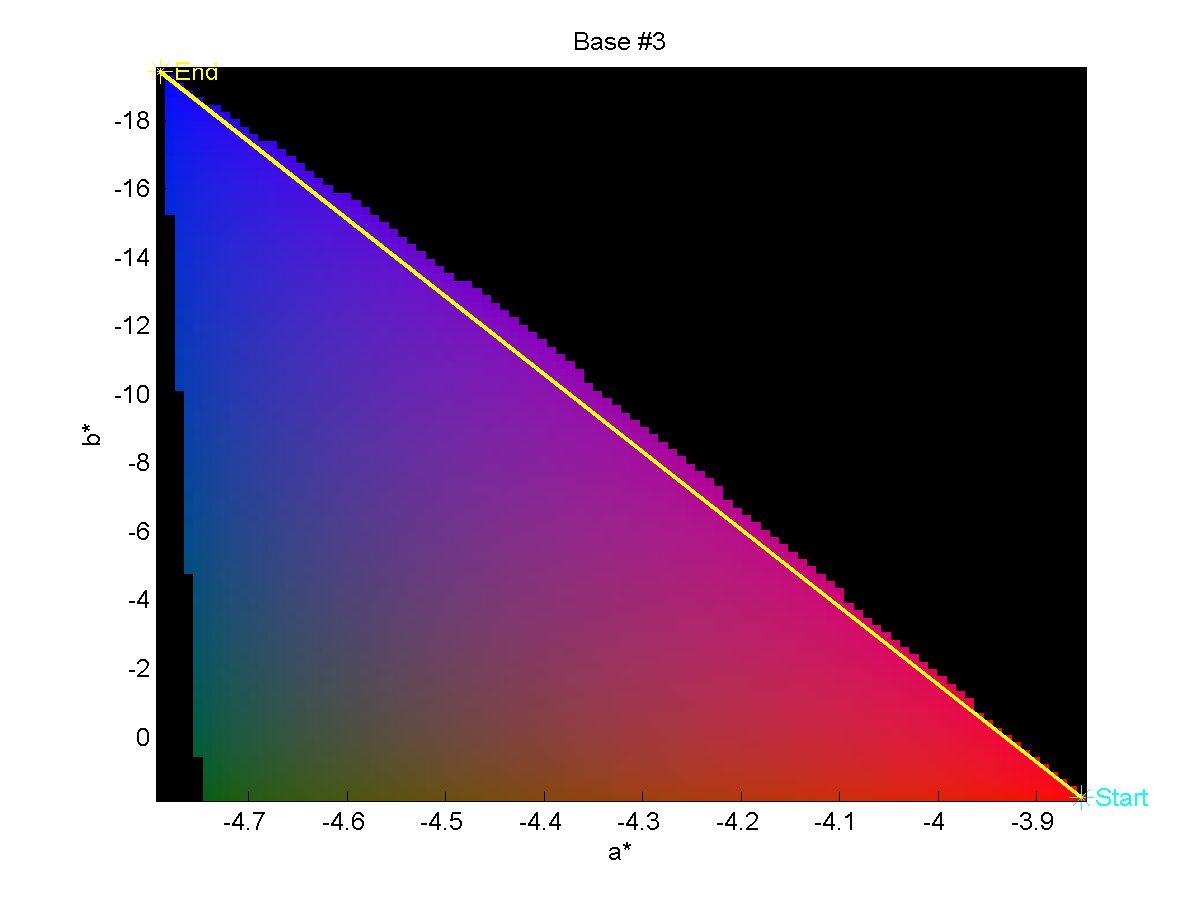

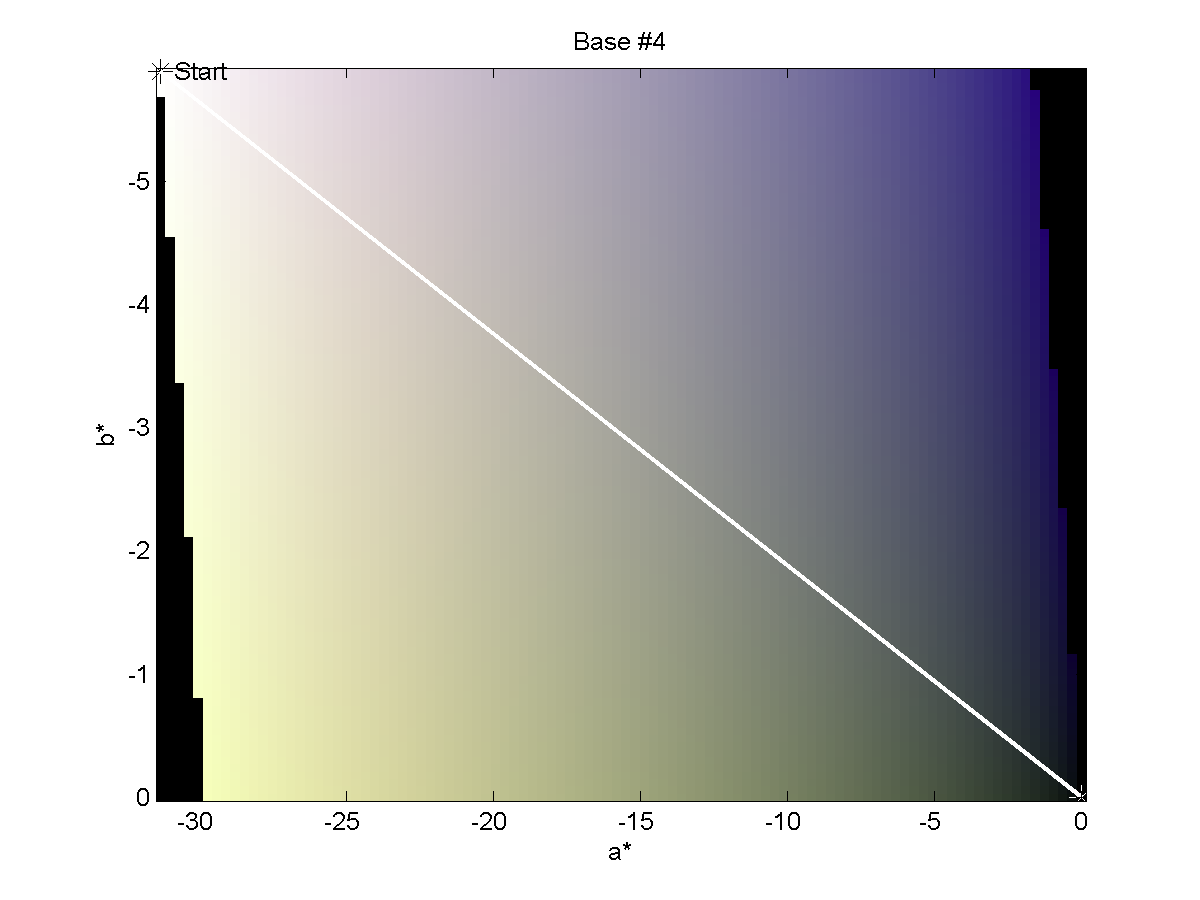

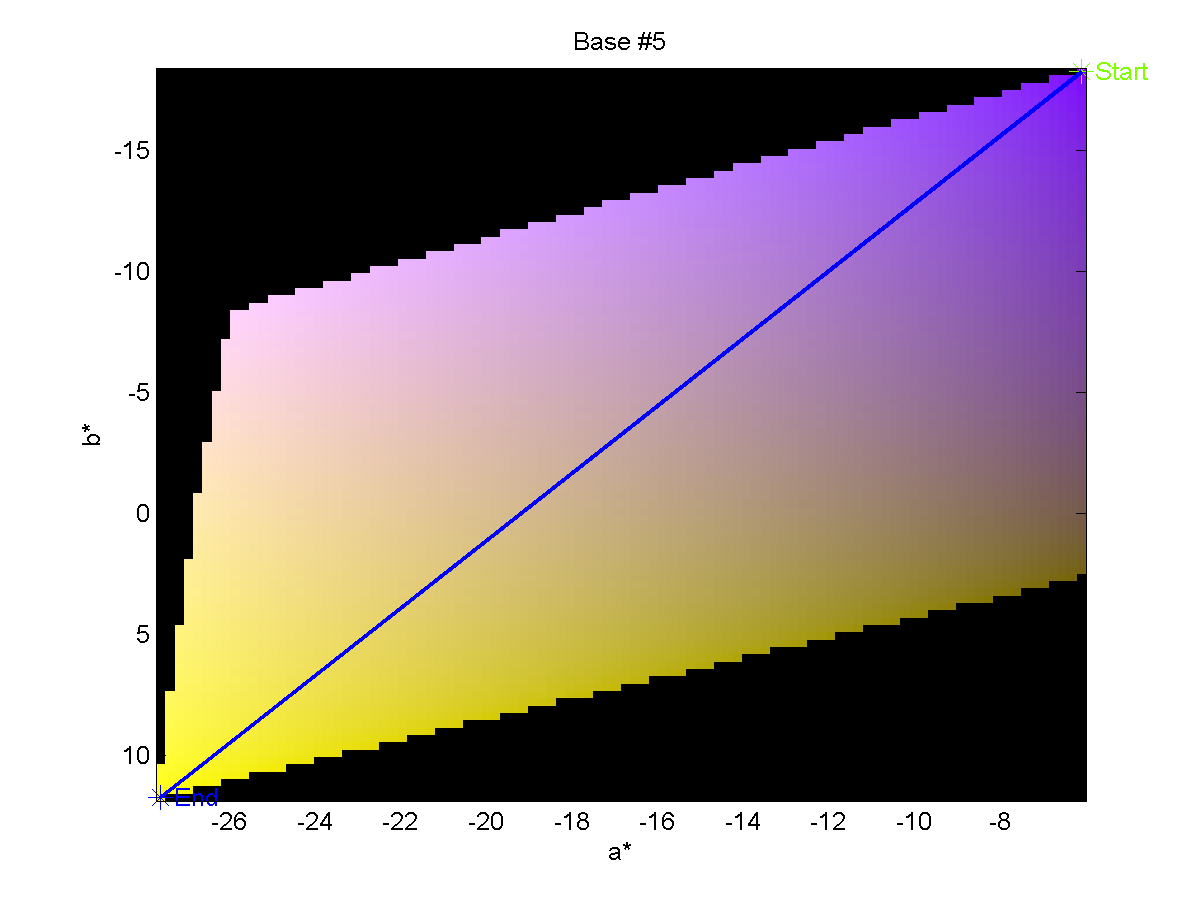

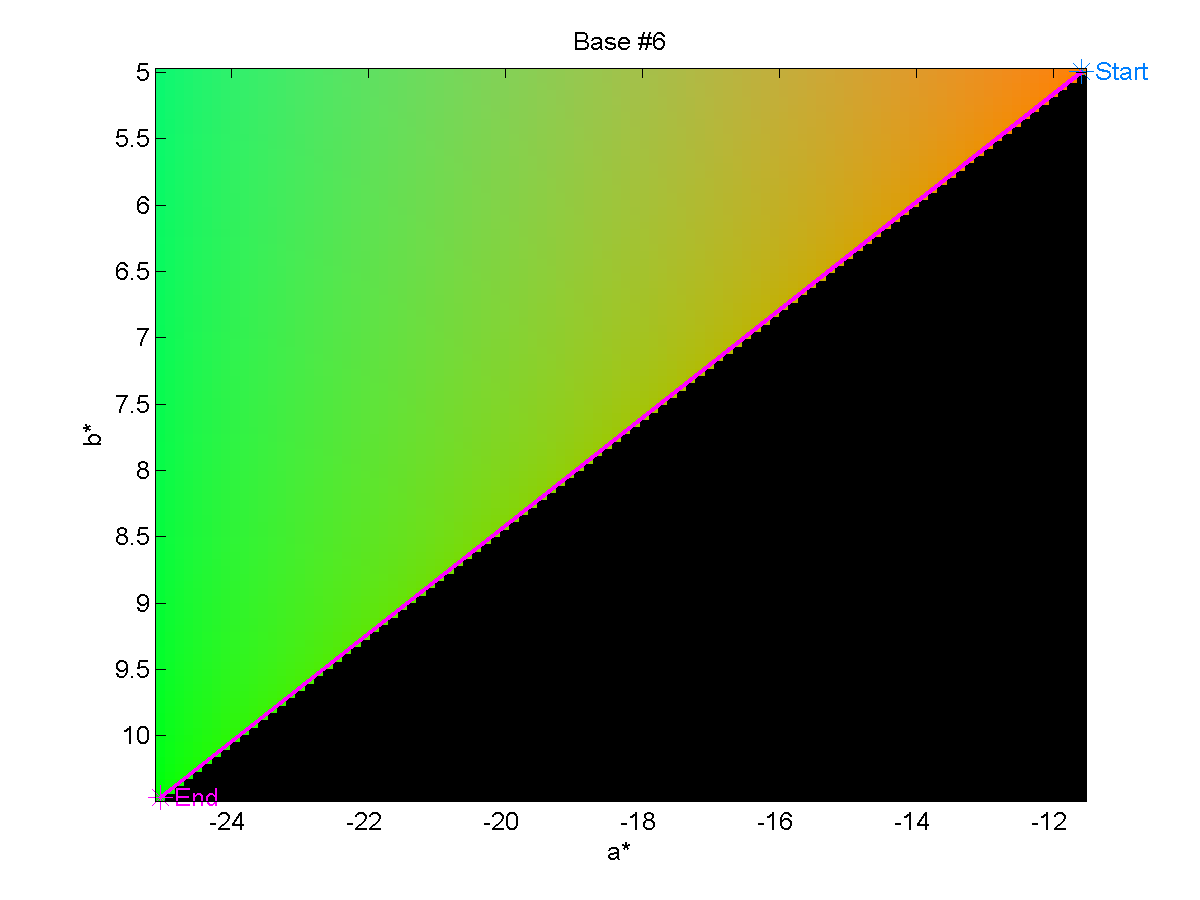

The following six two-part plots show the steps on the staircase for each

Base/End pair. In the upper portion of the plots, the CIELAB Euclidean distance

is shown for each Base/Alternate pair. In the lower portion of each plot, the

Alternate color is shown at the top, the Base color is shown at the bottom, and

the linear CIELAB interpolation is shown in the middle. Note that these plots

were generated with the same RGB values that were shown on our test monitor, but

because of differences in gamma and calibration, they will necessarily look

somewhat different on the medium on which you happen to be viewing them than

they did on our test monitor.

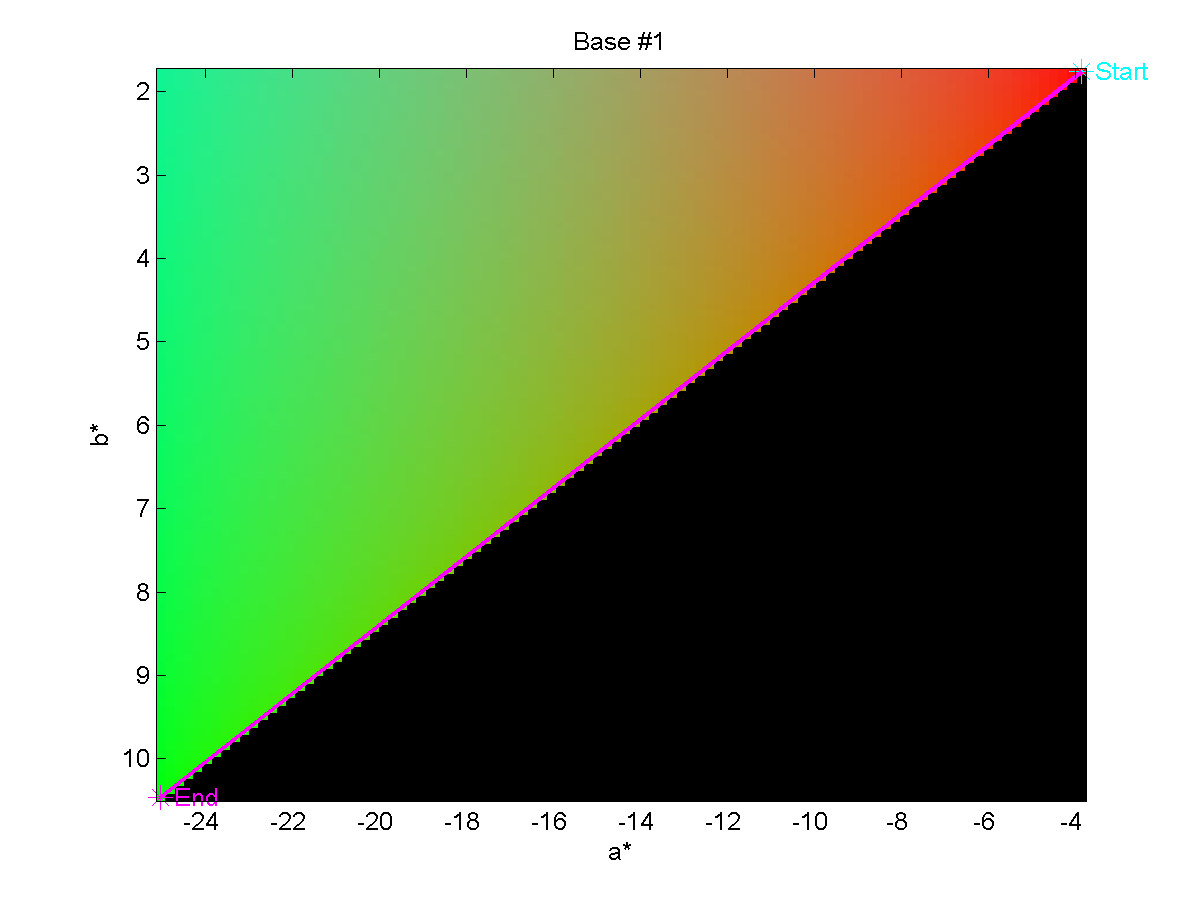

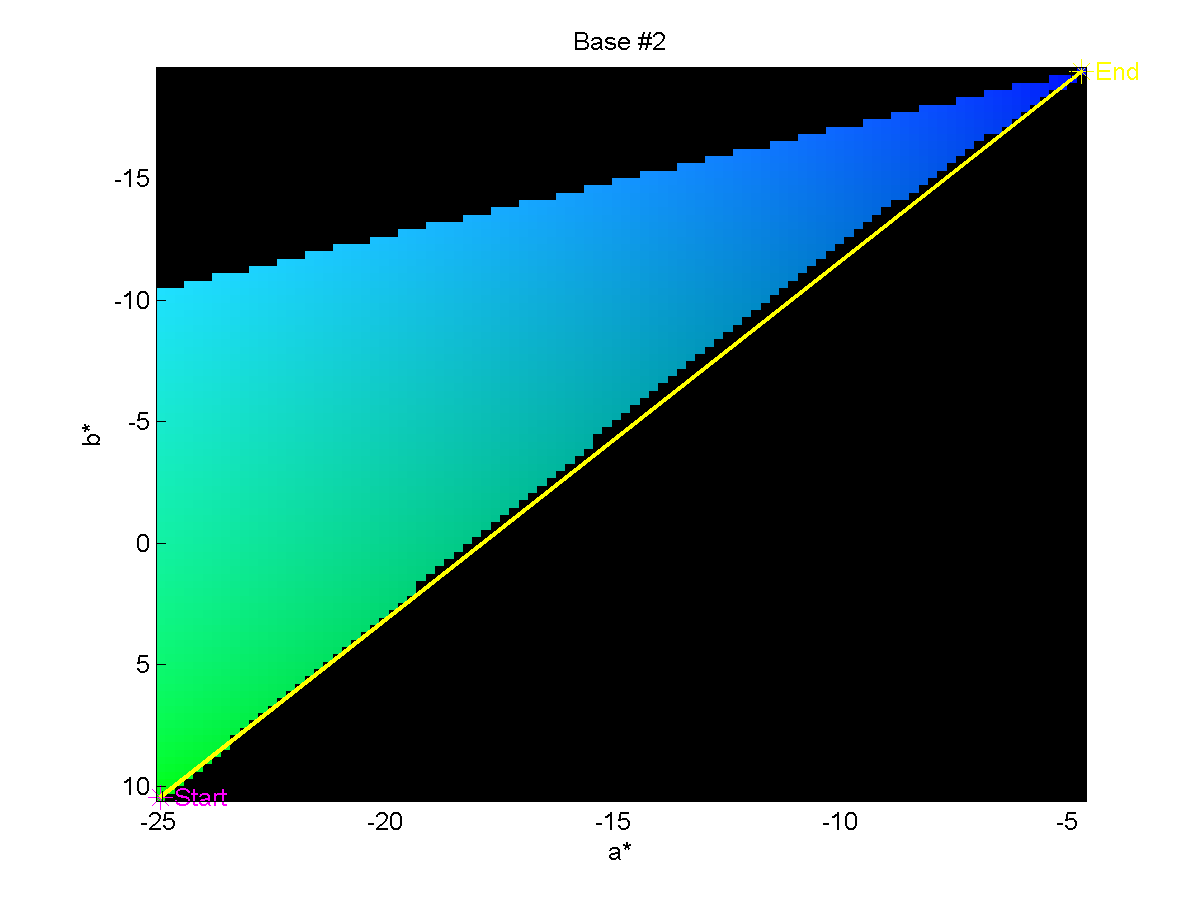

We may also show the paths from the Base to End colors on a planar cut through

the CIELAB color space to get a better feel of the space through which we are

traversing during the experiment. These images are shown below.

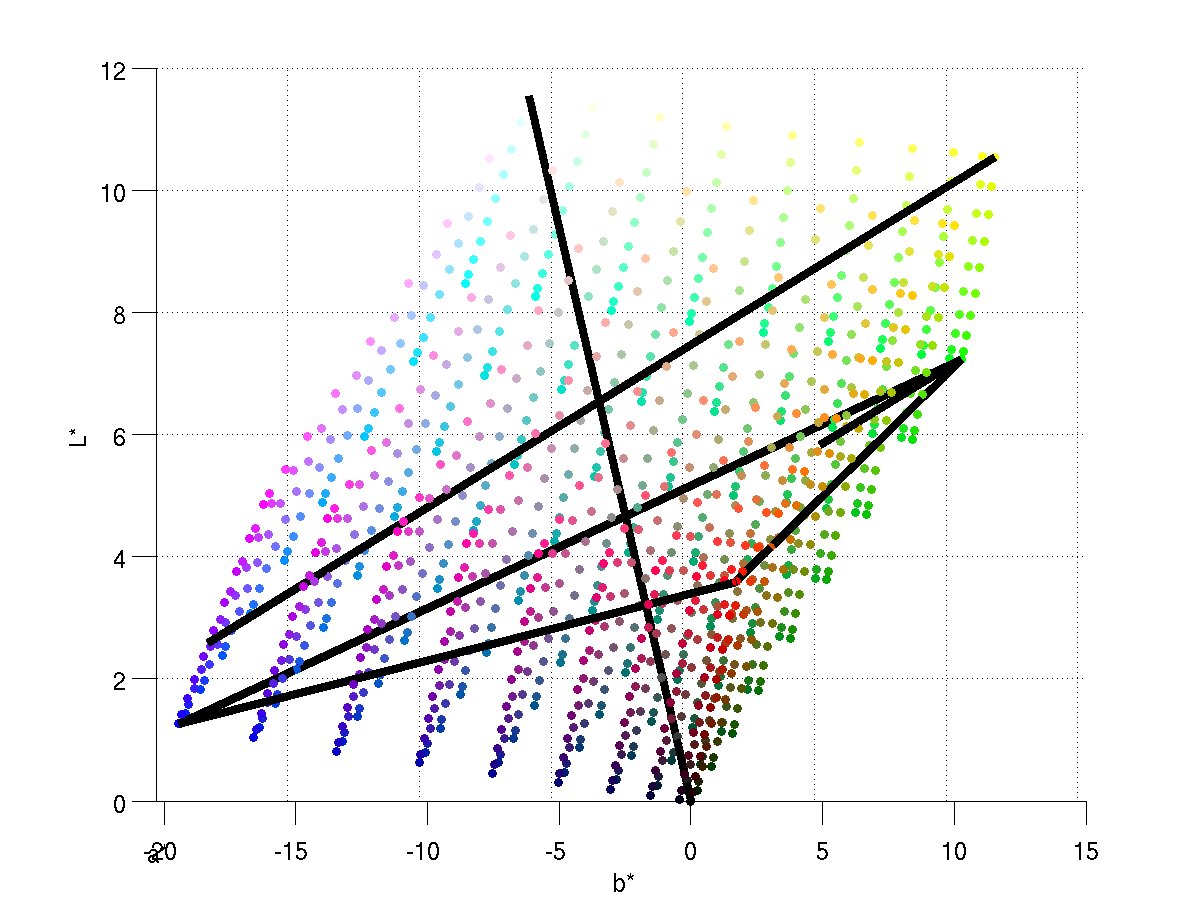

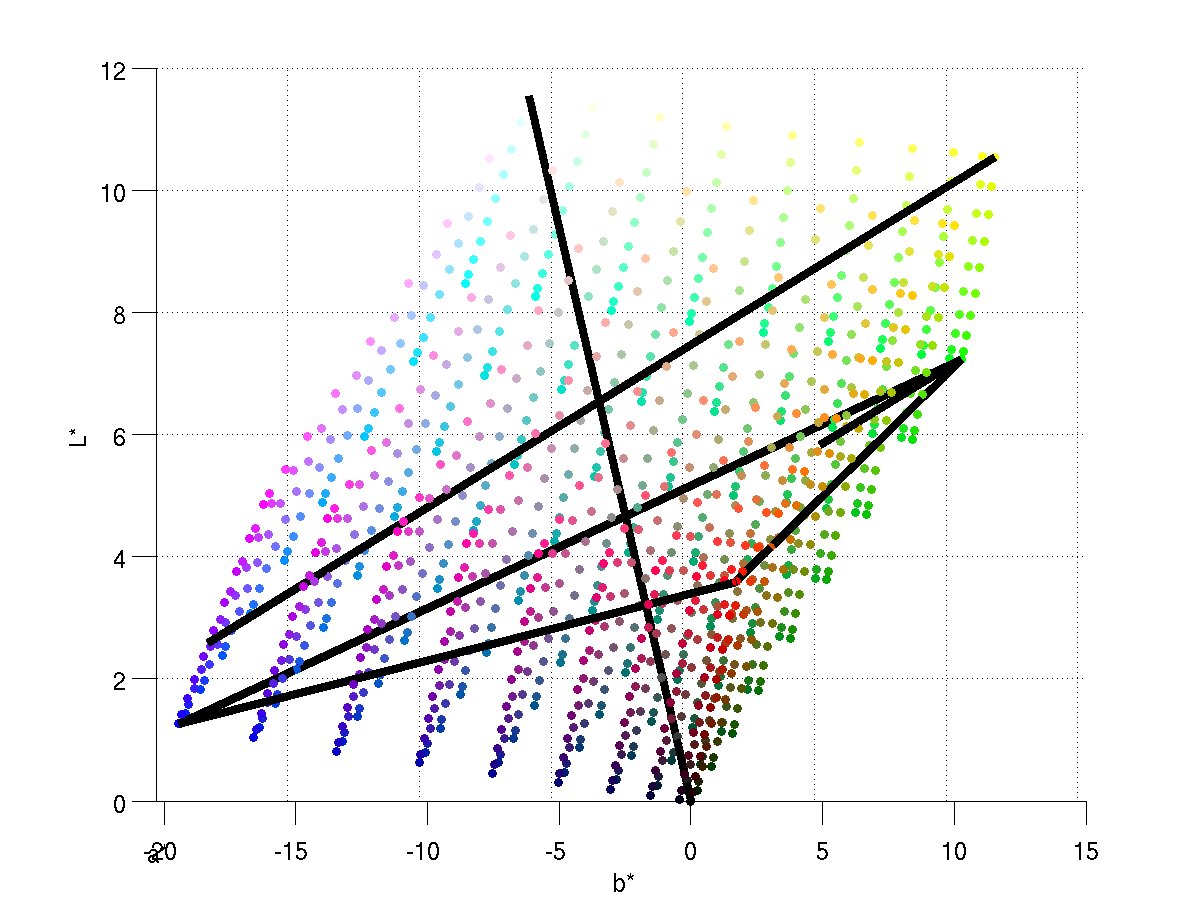

We can also simultaneously plot all of our trajectories through the RGB subset

of the CIELAB colorspace, as in the below plot. We can see that our experiment

samples a good portion of the RGB space.

Experiment Trajectories through RGB subspace of CIELAB space. The image is

projected onto the a* plane.

Experiment Trajectories through RGB subspace of CIELAB space. The image is

projected onto the a* plane.

Subject Information

Seven male graduate students at Stanford University served as subjects for this

experiment. Six subjects reported that their color vision was normal and one

subject reported Red-Green color-blindness. One subject, who is also one of the

experimenters, had previously undergone extensive self-administered flicker

photometry testing. Each was given a preliminary training session and was aware

of the test objectives.

Results

The results of the experiment were analyzed using Matlab. The code is included

in Appendix B.

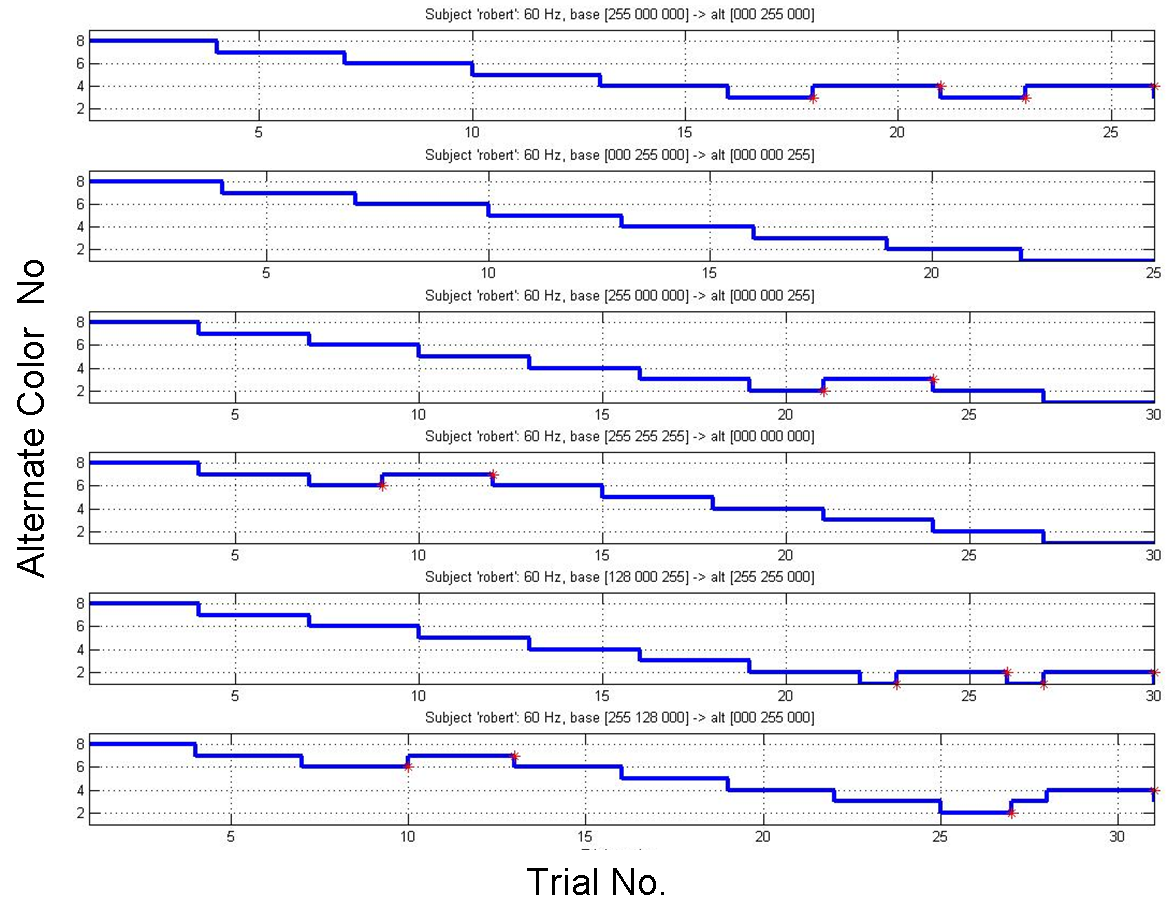

Staircase Plots

To determine the CFFDs, a staircase plot was produced for each subject. The

below figure, for example, shows a typical staircase plot. Each subplot

represents the subject's responsiveness to flickering along a single Base/End

pair axis. A descent in the staircase indicates that the subject accurately

identified flickering three consecutive times and was then shown the base and

a closer alternate. An ascent in the staircase indicates that the subject

could not accurately identify flickering and was again shown the previous base

and alternate. The red markers on the staircase plot indicate reversals, which

occur when the subject ascends or descends the staircase to a base and

alternate pair that he/she saw in the previous step.

Staircase plot for Subject "RN."

The staircase was designed to give a threshold resolution equivalent to

the height of a single step on the staircase. This is because it was assumed

that subjects would accrue most reversals between two adjacent steps on the

staircase (i.e., oscillate enough times between two adjacent alternates to

make it obvious that the threshold lay in between those steps). The results of

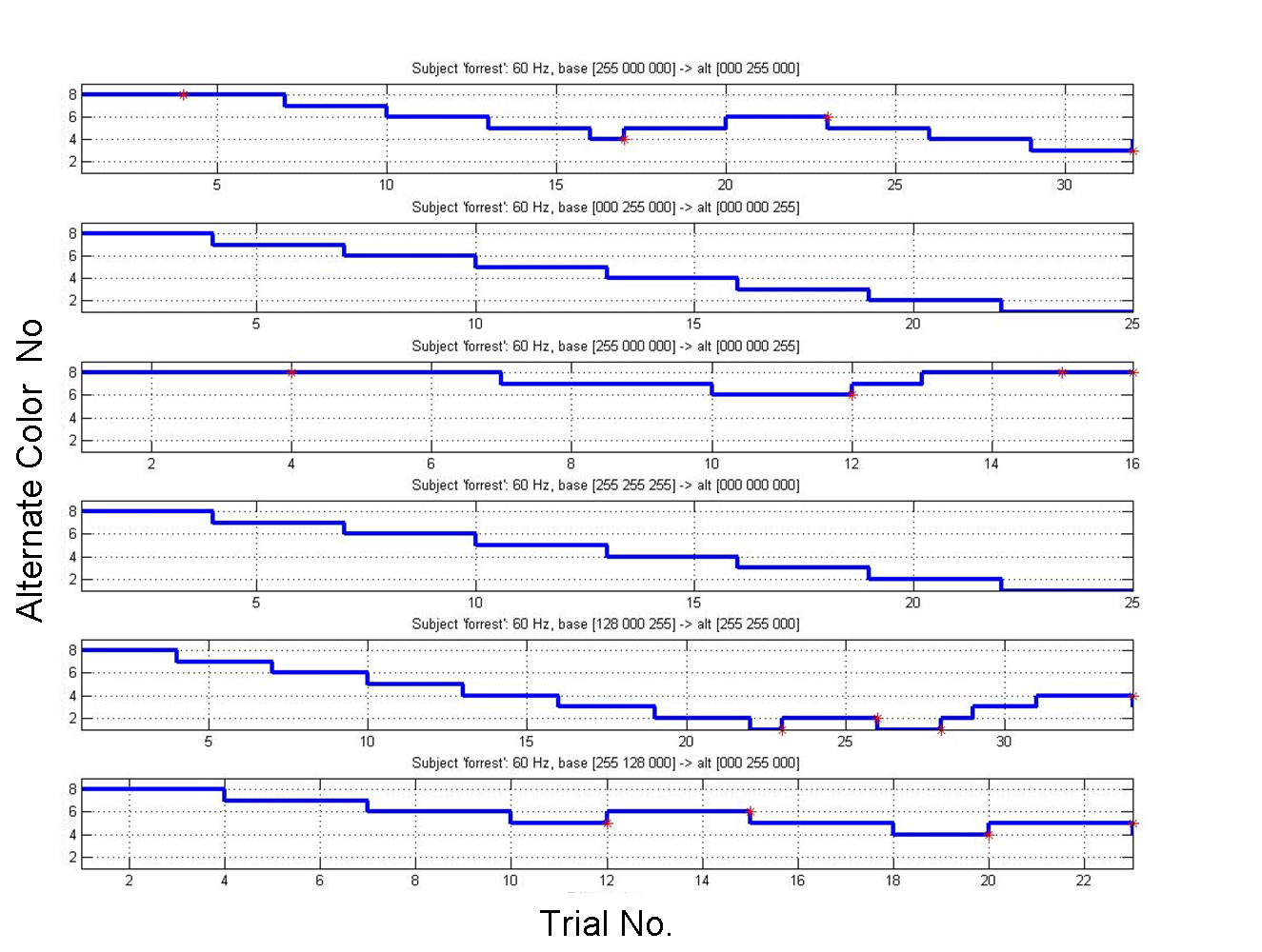

the experiments, however, showed that many subjects descended the staircase,

then ascended again by multiple steps. In the below figure, for example, the

uppermost subplot shows that the subject oscillated between steps 4, 5, and 6

for seven steps, then ended the test by descending to step 4. The average

threshold for these oscillations does not reflect a resolution of a single

step and inherits a large degree of uncertainty.

Staircase Plot for Subject "FF."

CFFD Calculations

The CFFD represents the Euclidean distance between the Base color and the

alternate color at the threshold. To determine this value for Base/End pair and

from each subject, the threshold step level was first calculated in each

staircase subplot. This was done by averaging the staircase levels during at

which the four reversals took place. In instances where there were less than

four reversals, such as when the user successfully descended the staircase to

the last step, the threshold was determined to be the last step. The CFFD was

calculated as the Euclidean distance between the base and threshold alternate

pair in LAB coordinates:

CFFD = sqrt[ (Lbase -

Lalt)2 +

(abase -

aalt)2 +

(bbase -

balt)2]

where Lbase, abase, and bbase are the LAB

coordinates of the base color and Lalt, aalt, and

balt are the LAB coordinates of the alternate color at the threshold.

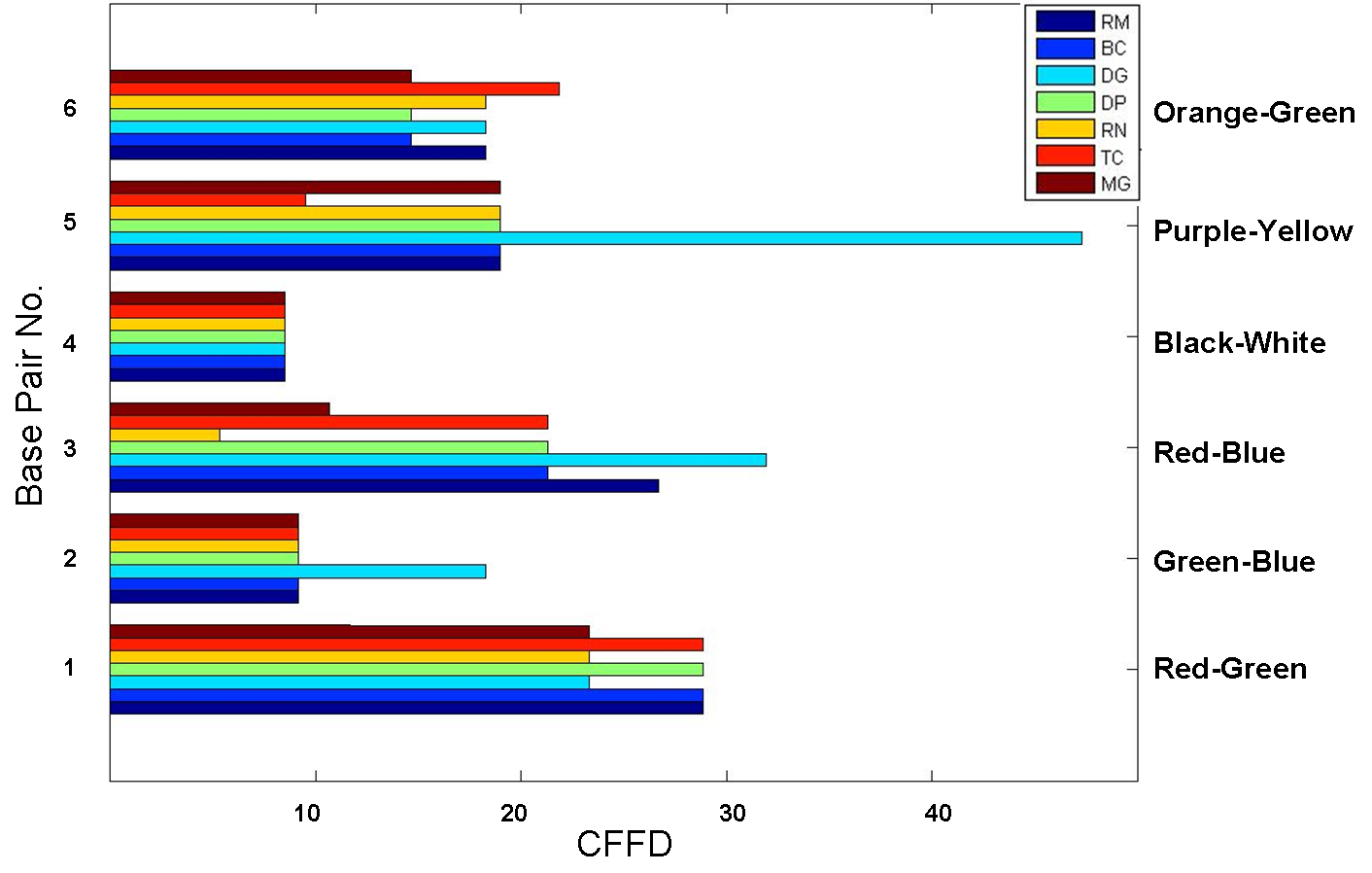

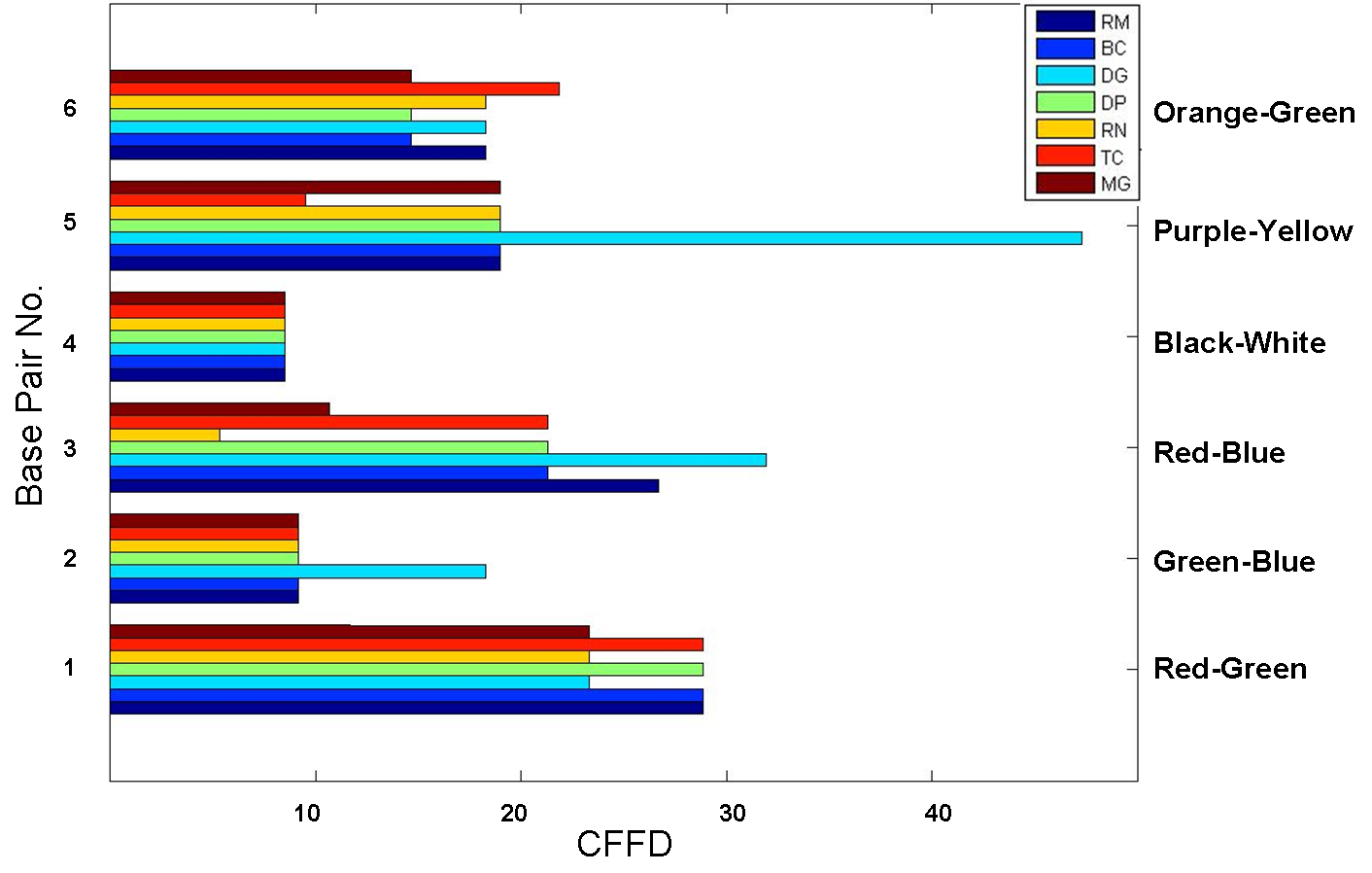

The CFFDs for each subject and Base/End pair is shown in the below figure. The

results show that all subjects were able to descend the staircase entirely for

Base/End Pair 4 (White/Black pair), achieving a CFFD of under 10 units. For

base/end pairs 1, 2, and 6 (Red/Blue, Green/Blue, and Orange/Green), the

subjects all achieved thresholds that were less than 10 units apart from each

other, corresponding to two steps on the staircase. One outlier in the results

was the Subject "DG" (results marked in light blue). This subject obtained a

threshold that was significantly higher than the average for base/end pairs

2,3, and 5. Though we will not make specific conclusions about this subject's

results, it is worthy to note that the subject (1) complained of eye dryness

due to wearing contact lenses, and (2) has taken the test at least ten

consecutive times before so his eyes might have been tired (3) was

particularly ornery due to point (2).

Critical flicker fusion distance (CFFD) for six base/end pairs from seven

subjects

Subject "TC" (results marked in bright red) was known to have red/green

color-blindness. Prior to the experiment, the subject reported difficulty in

differentiating red and green colors , but did not have specific information

about the degree of his color-blindness or his ability to differentiate

between differing levels of luminance. Interestingly, subject TC achieved the

same, if not lower, threshold than other subjects in all base/end pair tests,

except in the Orange/Green pair (in which his CFFD was higher by less than 5

units). This subject also performed the best in the Purple/Yellow pair test,

achieving a CFFD at least 10 units lower than all other subjects.

LAB Distances

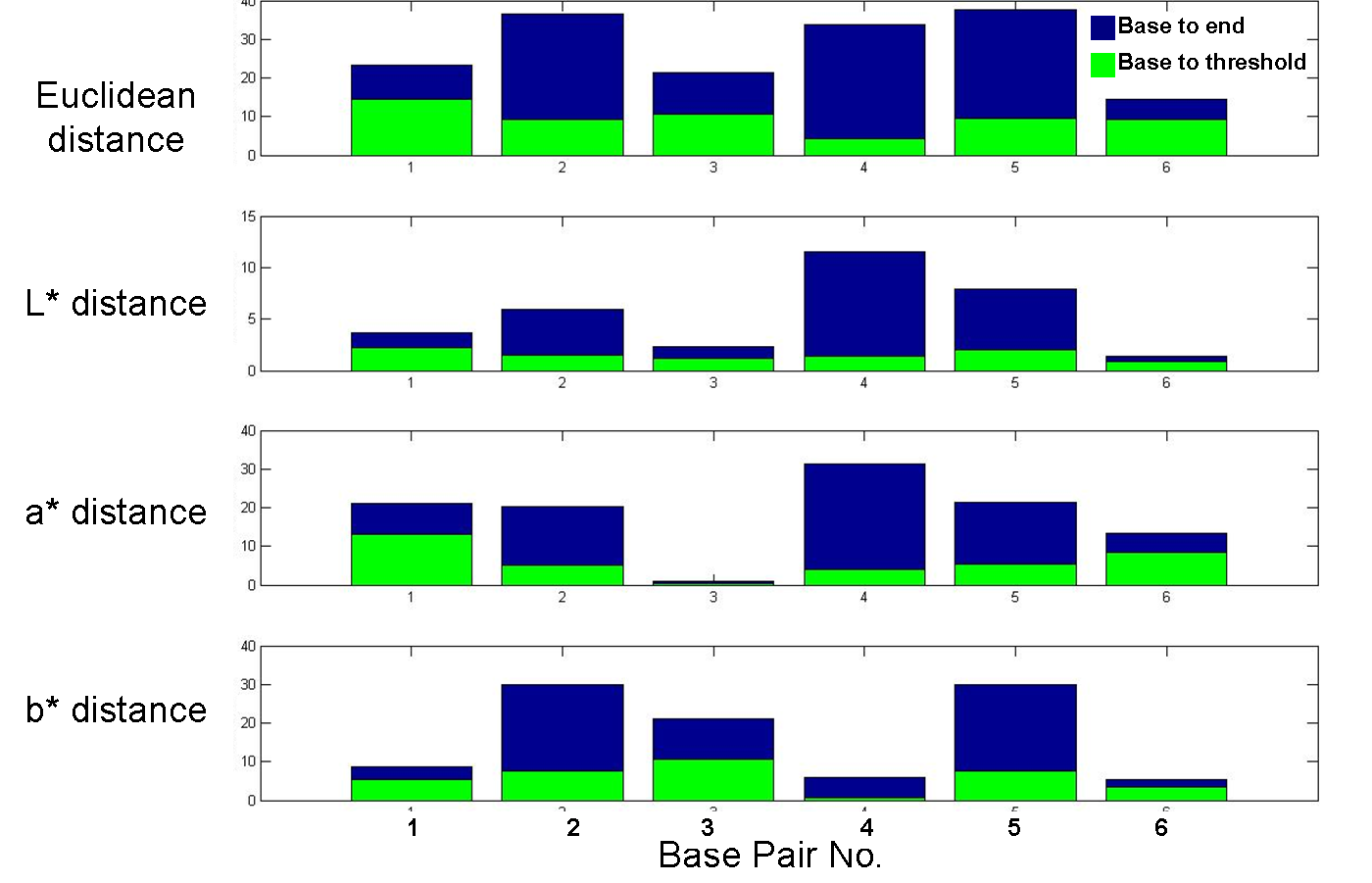

The below figure shows the differences in LAB coordinates for each base/end pair

in blue. The top subplot shows the Euclidean distance between the pairs, and the

lower three subplots show the L*, a*, and b* distances between the pairs. The

minimum Euclidean distance is between the orange and green pair, and the maximum

Euclidean distance is between the purple and yellow pair. The green bars,

superimposed on the blue bars, show the Euclidean, L*, a*, and b* distances

between the base and threshold colors (averaged over all subjects) for each

base/end pair. It is interesting to note that the Euclidean distance between the

base and threshold varies in the small range from 5-15 units. In fact, the L*

distance between the base and thresholds vary in the even smaller range between

1-2.5 units. The a* and b* distances are not confined to such narrow ranges.

These results suggest that the contrast in luminance (L*) plays the

largest role in determining a subject's ability to identify flickering,

regardless of where the base and alternate colors exist in the color space.

Indeed these results would also explain why the red/green color-blind subject

performed normally compared to other subjects if we assume that he does not have

trouble differentiating levels of luminance.

L*, a*, and b* distances between base and end colors, and base and

threshold colors

Comparison of Results to Previous Work

The results of this experiment agree with previous work in this field. The

Ferry-Porter Law, for example, states that the critical fusion

frequency (CFF) is proportional to the logarithm of the

luminance (L) of the flickering stimulus

and can be expressed as

CFF = K logL + C

where K and C are constants (De Lange 1958). This law

suggests that flicker fusion perception is most heavily related to luminance

(L*), and not as heavily related to chromatic composition (a* and b*). Indeed

other studies have shown that under photoptic conditions (in which cones are

excited, as opposed to rods), the CFF for lights of different

wavelengths with equal brightness also conform to the Ferry-Porter Law and

follow the logarithmic function as brightness increases. However, under scotopic

levels (when the rods are functioning), the CFF fans out for different

wavelengths.

In this experiment, we can assume that we are operating in photoptic conditions

since the monitor screen provides adequate brightness and color variations to

excite the cones. Thus the results agree with the previous work, showing that

contrast in luminance is the greatest factor in identifying flicker, regardless

of color.

Conclusions

In this experiment, the critical flicker fusion distance was measured for six

pairs of base/end color pairs that spanned the RGB space using 8 subjects. The

results showed that the difference in luminance between the base and alternate

color matter significantly more than (1) the distance between the base a* and

alternate a*, (2) the distance between the base b* and b*, and (3) location of

base color in the color space, and (4) direction in color space along which the

alternate is chosen.

The results also suggest that Red/Green color-blind individuals will have

equivalent ability to identify flickering, assuming that their ability to detect

contrast in luminance is not impaired.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank several members of the Stanford Vision Science and Neuroimaging

Group, in particular Bob Dougherty, Joyce Farrell, Kaoru Amano, Serge Dumoulin,

and Brian Wandell.

Authors

(Subject SB, who inexplicably developed an ear infection immediately after the

experiment)

(Subject DG, whose orneriness during experimentation was later

found to be a preexisting condition)

References

De Lange DZN H (1958) Research into the Dynamic Nature of the

Human Fovea® Cortex Systems with Intermittent and

Modulated Light. II. Phase Shift in Brightness and Delay in Color Perception.

J Opt Soc Am 48: 784-789.

Hart Jr, WM (1987) The temporal responsiveness of vision. In:

Moses, R. A. and Hart, W. M. (ed) Adlers Physiology of the eye, Clinical

Application. St. Louis: The C. V. Mosby Company.

Kelly DH (1974) Spatio-temporal frequency characteristics of

color-vision mechanisms. J Opt Soc Amer 64: 983-990.

Truss (1955) Chromatic Flicker Fusion Frequency as a Function of

Chromaticity Difference. Journal of the Optical Society of America 47:12:

1130-1134.

Tyler CW and Hamer RD (1990) Analysis of visual modulation

sensitivity. IV. Validity of the Ferry-Porter law. J Opt Soc Amer A

7:743-759.

Appendix 1: Source Code

Source Code for the experiment can be accessed at

http://www.stanford.edu/~dgolden1/sbijoor_dgolden_psych221_final_proj.tar.gz

Appendix 2: Work Breakdown

The work for this project was shared equally by Dan and Sheila, and included:

-

Designing experiment

-

Conducting literature review

-

Writing code for stimuli and staircase method

-

Arranging experimental set-up

-

Calibrating monitor

-

Conducting experiments

-

Analyzing results

-

Presentation

-

Report