|

|

|

|

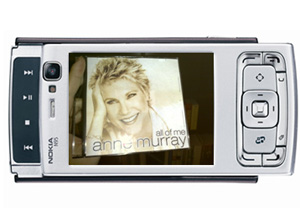

I. Introduction Cell phones equipped with cameras, or camera-phones, can now capture high-resolution photos. The increased proliferation of camera-phones has popularized the field of mobile augmented reality (MAR), in which a mobile device captures a photo of an object of interest and automatically retrieves information about that object from a remote database. For example, the MAR system in [1] can perform real-time identification of buildings on a camera-phone, as depicted in Fig. 1, to provide virtual tours. Our own work has recently focused on automatic recognition of CD covers using a camera-phone, as depicted in Fig. 2, to enable customers to sample music before purchasing.

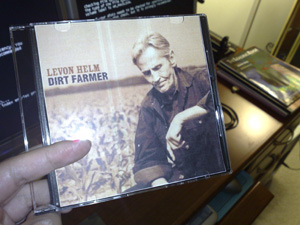

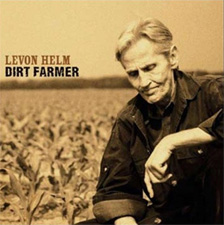

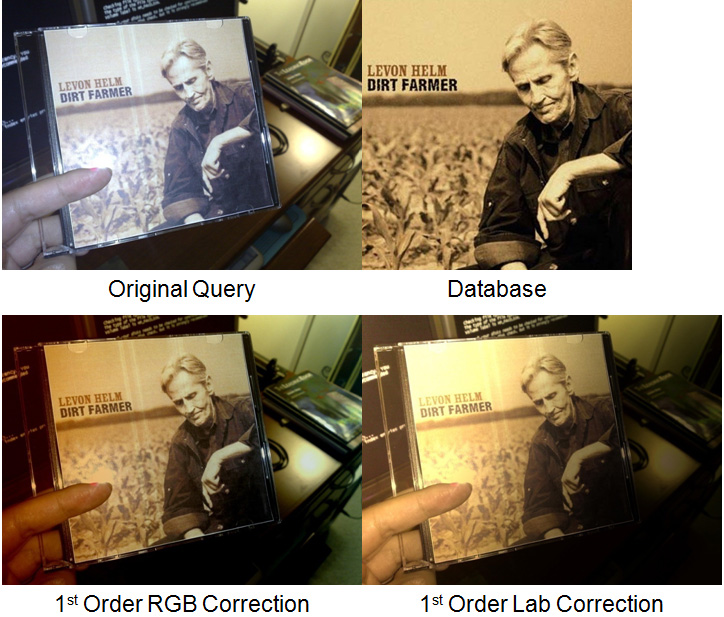

The key problem in all MAR applications is to accurately match a query image captured by the camera-phone to a corresponding image in the database. There are practical issues that make this matching problem difficult. Images of the same scene taken from different positions can be dissimilar when there is perspective transformation, illumination variation, or occlusion. Fig. 3 shows a query image for a CD cover, and Fig. 4 shows the corresponding clean database CD cover. Relative to Fig. 4, the CD in Fig. 3 shows all of the aforementioned distortions. Additionally, there is background clutter that can confuse a matching algorithm. To correctly match Fig. 3 and 4, the matching algorithm must be robust against all of these problems.

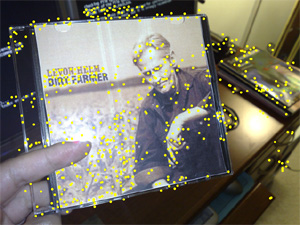

In the last few years, the computer vision community has developed a class of robust features that are mostly invariant to the typical distortions. Scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT), proposed by Lowe [2], extracts features from images which survive the typical geometric and lighting distortions. A similar but simpler technique called speeded up robust features (SURF), proposed by Bay et al [3], produces more compact features with equally good matching performance. Fig. 5 shows an example of SURF features for the query CD image of Fig. 3, where the yellow markers represent the locations of detected features. The feature extraction pipeline common to both SIFT and SURF will be reviewed in Section II, along with a discussion of how to use these features to reliably match query and database images. As a practical application, it will be shown that robust features enable accurate matching between query and database CD covers.

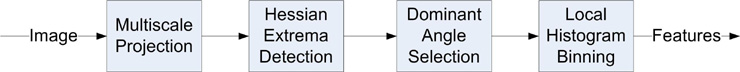

Previously for CD recognition, the primary goal for image matching was to send descriptive information about the CD content from the database to the camera-phone. The label of the CD can be overlaid on the phone's screen and a sample of music can be played for the potential buyer. In this project, we exploit the features that are already available from the matching process to solve an additional problem: color restoration of the query CD cover. When comparing Fig. 3 and 4, notice how there are significant color differences between the CD covers. If we want the query CD to look like its database counterpart, we must correct these color differences. Correcting for color mismatch is a worthwhile goal, particularly if it can be done efficiently. Suppose while on a trip, a person has a picture taken of herself in front of a landmark. The photo is taken under poor lighting conditions, say under cloudy skies. Instead of retaking that photo and meticulously trying to recapture the moment, the person can find a previous reference photo of the landmark taken under good lighting conditions. Using the feature-based color restoration technique we present here, that person can re-light the target photo. Thus, our method will allow automatic realistic enhancement of photos. Section III will present an effective color restoration algorithm based on robust feature correspondences between query and database. The algorithm can be flexibly applied in either the RGB color space or the CIELAB color space. Experimental results in Section IV demonstrate that the subjective visual quality of the query CD covers is significantly improved by our color restoration technique. Objectively, the mean-squared-error (MSE) between the query and database CD covers is also greatly reduced. Although the current experiment focuses on restoration of CD covers, the method is more widely applicable to restoration of any object of interest in a digital photograph. Camera-phone users can capture new photos without being excessively worried about ideal lighting. As long as previous clean photos of the object of interest exist in the database, degradations in the new photos can be reduced and the object of interest can be enhanced. Automatic post-photography restoration becomes an interesting new application in the MAR framework. II. Image Matching Feature extraction Robust features like SIFT [2] or SURF [3] are designed to be strongly invariant to common geometric and lighting distortions. The feature extraction pipeline common to both SIFT and SURF, illustrated in Fig. 6, selects features from the image which can survive the typical distortions. Let us consider how reliable features are found in a query image. First, the query image is projected onto different scales (resolutions) by upsampling and downsampling with a Gaussian filter. This step addresses a serious problem with other corner detectors like the Harris detector [4] which are unable detect strong corners at very large or small scales. Second, the algorithm searches for extrema in the Hessian at the different scales. The Hessian at point (x,y) for an image intensity function f(x,y) is the matrix of second derivatives

Extrema in the Hessian correspond to distinctive corners which are robust against geometric and lighting distortions. Examples of these Hessian extrema are found in Fig. 5 above. These points of interests are considered most reliable in image matching. Then, to achieve rotation invariance, the dominant orientation around each point of interest is calculated. Finally, a square neighborhood is fit around the point of interest. The size of the square is determined by the scale at which the Hessian extremum is detected in the earlier stage. Similarly, the rotational angle of the square is determined by the dominant orientation previously determined. In this square neighborhood, vertical and horizontal (in the sense of being parallel with the sides of the rotated square) histograms are calculated. A vector of these histogram values represents the full feature. Multiple features, one for each point of interest, then serve as a robust hash for the query image.

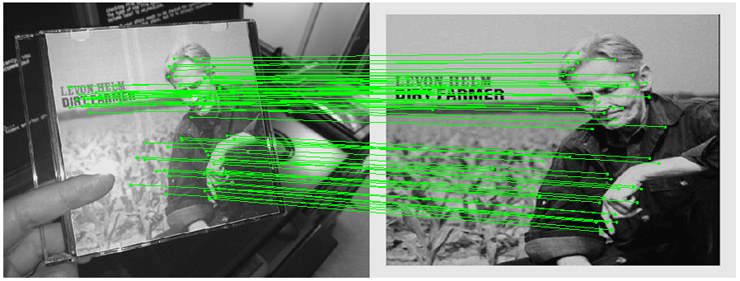

Likewise, features can be extracted from each database image. The problem of image matching turns into the problem of comparing different sets of features. Whichever database image has a feature set most similar to the query image's feature set, that database image is judged to be the closest match. Ratio Test The ratio test of distances is proposed to improve matching accuracy [2]. For query feature q, let the two database features closest in Euclidean distance to q be denoted as p1 and p2. Let the corresponding distances be d1 = ||q - p1|| and d2 = ||q - p2||, where d1 < d2. Then, q passes the ratio test if and only if where 0 < r < 1 is the ratio threshold. Smaller values of r force the closest match p1 to have much smaller separation from q than the second closest match p2. Intuitively, those query features which pass the ratio test are very distinctive, having only one close match in the database set. Let the set of query features be denoted Q. When comparing Q against database set Di (1 < i < # database candidates), the number of query features that pass the ratio test NRT,i is recorded. The M database images with the M highest values of NRT,i are selected to be the most likely matches for the query image. Geometric Consistency Check The final task of the feature-based image matching algorithm is to find the correct match out of the M most likely database images after the ratio test. A geometric consistency check is performed, to make sure the feature correspondences between query and database satisfy a physically realizable transformation. For example, extreme shears, stretches, or twists are very unlikely to occur in reality. An affine or perspective model is calculated by random sample consensus (RANSAC) [5] on the post-ratio-test feature correspondences. For example, a valid affine model that links a query CD cover to the correct database CD cover is depicted in Fig. 7.

RANSAC is an iterative algorithm. Features whose locations which do not fit the current geometric model are classified as outliers and eliminated. Then, the model is re-estimated given the newly identified set of inliers. By iteratively removing outliers and updating the geometric model, the RANSAC algorithm converges to an optimal model where all outliers are removed. The number of post-RANSAC features NGCC,i for database set Di is a very strong indicator of the accuracy of matching Di to the query set Q. Usually, a correct match between query and database has a much higher value of NGCC,i than an incorrect match. Thus, in the CD recognition experiment for this project, we use the post-RANSAC count NGCC,i to make the final determination of which database CD should be reported. The transmission cost of features is low compared to the size of the color query image. Each 2592 x 1944 color query image requires on average 644 kilobytes after JPEG compression at a high (but not lossless) quality. Each set of features requires on average only 96 kilobytes, less than 15 percent of the compressed image's size. Thus, it is much more efficient to extract features on the camera-phone and send these features for matching than it is to send the compressed query image. III. Color Restoration Different color distortion models have been previously proposed. In general, the spectral power distribution (SPD) of an object captured by the camera is the product of the object's body reflectance and the illuminant's SPD [6]. The body reflectance summarizes the true color information, but this information is lost when multiplied with the illuminant's SPD. Since the SPD is ultimately reduced a simple RGB description, it is unnecessarily complex to try to estimate the body reflectance. Digital restoration of faded motion pictures is described in [7]. The model presented there is not spatially variant and cannot correct for distortions such as linear gradients. Color restoration for fresco preservation is investigated in [8], and the authors selected color histograms for image retrieval. Unfortunately, color histograms are not robust against illumination distortions, which is why SIFT and SURF only use luminance to extract robust features. Our work is most similar to that reported in [9], in which the authors apply linear regression to estimate color distortion from sample patches. In their work, however, the clean and dirty images have collocated pixels and no geometric distortion between them. Our technique allows for geometric distortion between query and database. Linear Restoration Model In Section II, we demonstrated that reliable matching between query and database CD covers can be achieved using robust features, specifically SURF in our implementation. The feature correspondences which pass the ratio test and geometric consistency checking are fairly accurate. Thus, we rely on these strong feature matches to solve the problem of color restoration for the query CD cover. As a reminder, our goal is to make the query CD cover, in its current pose and orientation, look more similar in color to the database CD cover. Suppose (xq*, yq*) is a feature point in query image Q(xq, yq) which has passed the ratio test and geometric consistency checking. Let the corresponding feature point in database image D(x,y) be (xd*, yd*). As a matter of notation, (xq, yq) emphasizes that the point lies in the query image's coordinate system, while (xd, yd) means the point lies in the database image's coordinate system. The color values Q(xq*, yq*) and D(xd*, yd*) give us one sample of the color difference function (CDF) d(xq, yq) d i (xq*, yq*) = D i (xd*, yd*) - Q i (xq*, yq*) (i = 1, 2, 3) where index i loop over the color channels, such as R = 1, G = 2, B = 3. The CDF is the error causing the query CD cover to look dissimilar in color compared to the database CD cover. If we can accurately estimate d(xq, yq), we can undo the distortion and restore the query CD cover to its original correct colors. Although the feature correspondences only give us a sparse sampling of d(xq, yq), if d(xq, yq) is a slowly varying function across space, then the entire function can be accurately predicted from its samples. In fact, a linear model is sufficiently accurate for the CDF in most query images. The linear model has three parameters [a, b, c] and the form The parameters [a, b, c] can be estimated by a least squares fitting of all the samples. Specifically, from the N post-ratio-test, post-RANSAC feature correspondences { (xq,1, yq,1) ... (xq,N, yq,N) } <--> { (xd,1, yd,1) ... (xd,N, yd,N) }, form the matrix relationship

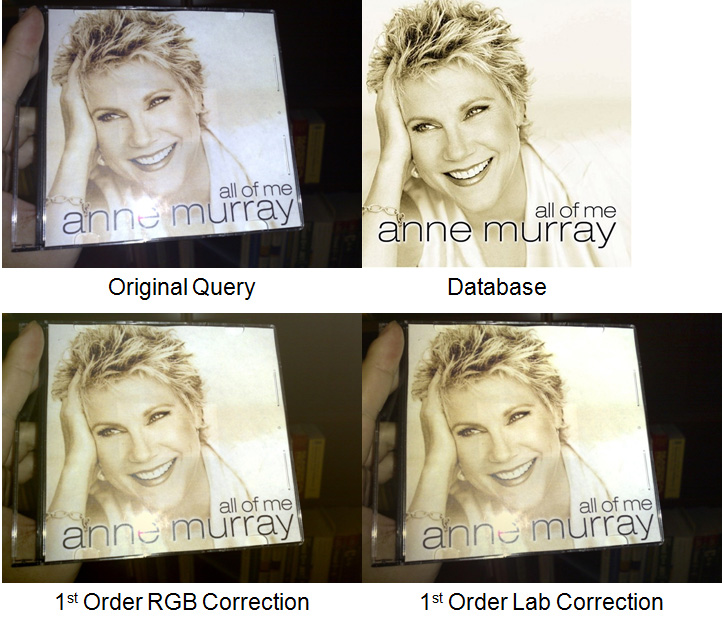

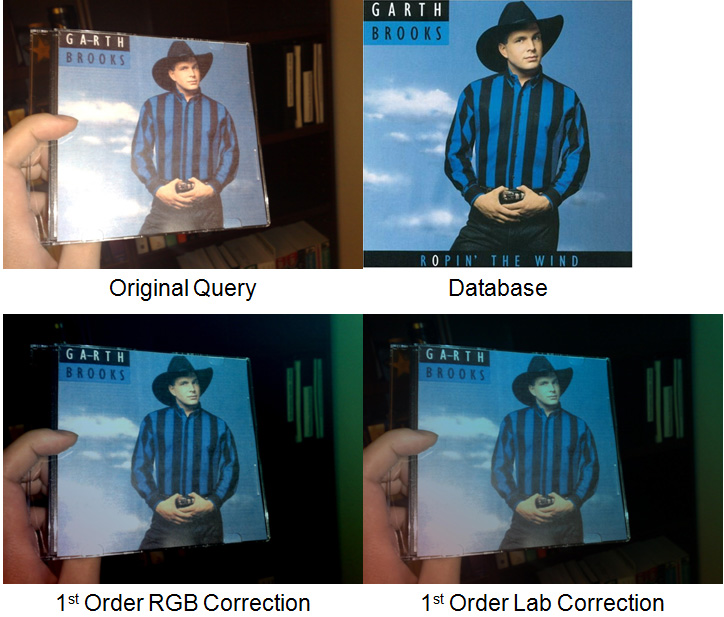

The system of equations is overdetermined and a least squares solution is appropriate for minimizing the expected modeling error. Solving for the least squares parameters ai* = [ai*, bi*, ci*]T we get Despite its simplicity, the linear model works well in practice. Lighting distortions seen in the majority of query images can be approximated by linear gradients and constant shifts. The experiments also tested a quadratic model, but the quadratic model did not give visually noticeable gains over the linear model. Furthermore, the quadratic model was less stable, sometimes severely overcompensating in regions away from the sample locations. The proposed model works for any three-channel color representation. A color correction can be calculated in the original RGB space, in a gamma-corrected RGB space, in the XYZ space, in the CIELAB space, just to name a few examples. For this project, we report results for RGB and CIELAB. As mentioned previously, the transmission cost of features is very low compared to the transmission cost of the compressed query image. The transmission cost of the post-ratio-test, post-RANSAC color samples needed for restoration is even lower, only 4 kilobytes on average or less than 1 percent of the compressed query image's size. Thus, color restoration information can be communicated very efficiently. IV. Results Match Results for CD Covers To evaluate matching performance, we constructed a test database and test query set of CD covers. The database contained a diverse assortment of 480 color CD covers, of resolution 500 x 500. To construct the test query set, we printed 50 database covers and inserted the color cutouts into actual jewel cases. A Nokia N95 camera-phone was used to photograph the query CD's, as depicted in Fig. 2, under some challenging conditions. The lighting was often uneven and camera flash produced glare on the CD surface. Depending on how the CD was held, there were varying degrees of perspective distortion. False features were also triggered by the appearance of non-CD objects, like a computer screen or bookshelf in the background and a human hand holding the CD in the foreground. Each query image has maximum resolution 2592 x 1944, but since reliable feature detection only requires 640 x 480 resolution and the luminance component, each color query image is downsampled and converted to grayscale prior to feature extraction. SURF was chosen over SIFT because SURF has more compact feature vectors without loss in matching accuracy on the average. Under these test settings, 49 of the 50 query images are successfully identified, resulting in 98 percent match rate. The only image which fails has an insufficient number of descriptive features. Thus, the first part of this project demonstrates that accurate CD recognition on a camera-phone can be achieved with feature-based image matching. Color Restoration Results for CD Covers Significant visual improvement for color CD covers can be obtained by applying the proposed color correction. Fig. 8, 9, and 10 show three sets of CD covers. In all three examples, the colors of the query CD are noticeably distorted compared to the colors of the clean database CD. Both the linear RGB and linear CIELAB corrections undo most of the color distortion and restore the query CD covers to their natural colors.

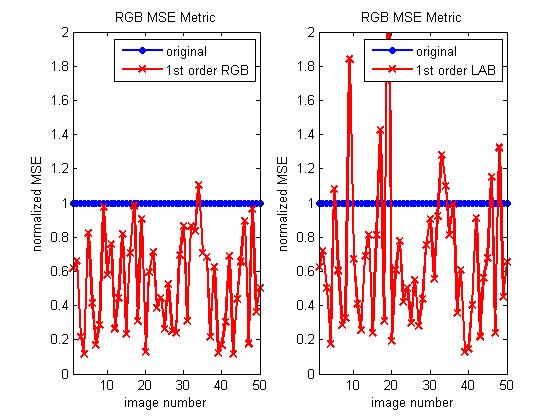

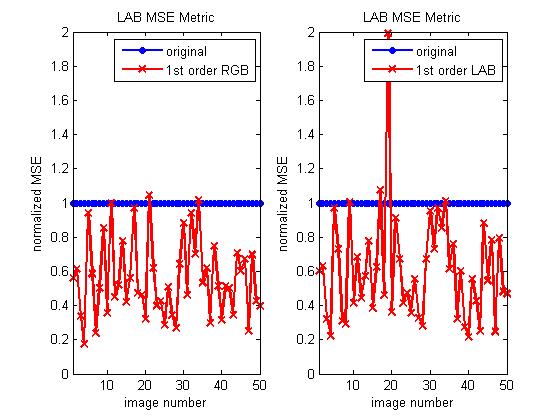

Besides subjective quality improvement, the proposed restoration technique also reduces the objective MSE of the query CD cover relative to the database CD cover. To obtain meaningful MSE measurements, the query CD cover is projected from its current pose into a rectified 500 x 500 square. The MSE between the transformed query CD cover and the 500 x 500 database CD cover can then be calculated. Fig. 11 and 12 display the MSE between transformed query and database CD covers measured in the RGB and LAB spaces, respectively, for all the query images. In these plots, the MSE is normalized with respect to the MSE of the original query CD cover without color restoration. Thus, the normalized MSE of the original query is a flat line at unity. If the normalized MSE of the restored query falls below unity, then restoration has successfully reduced the objective MSE mismatch between query and database.

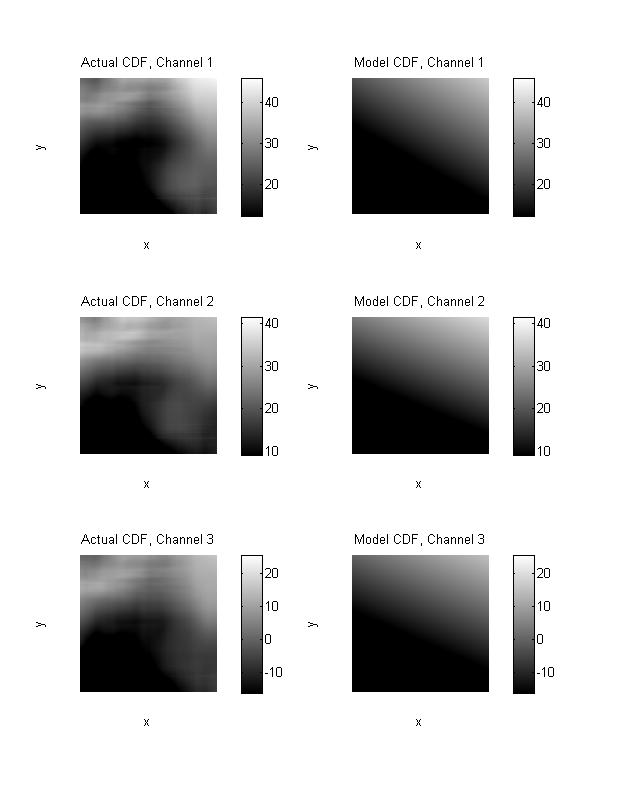

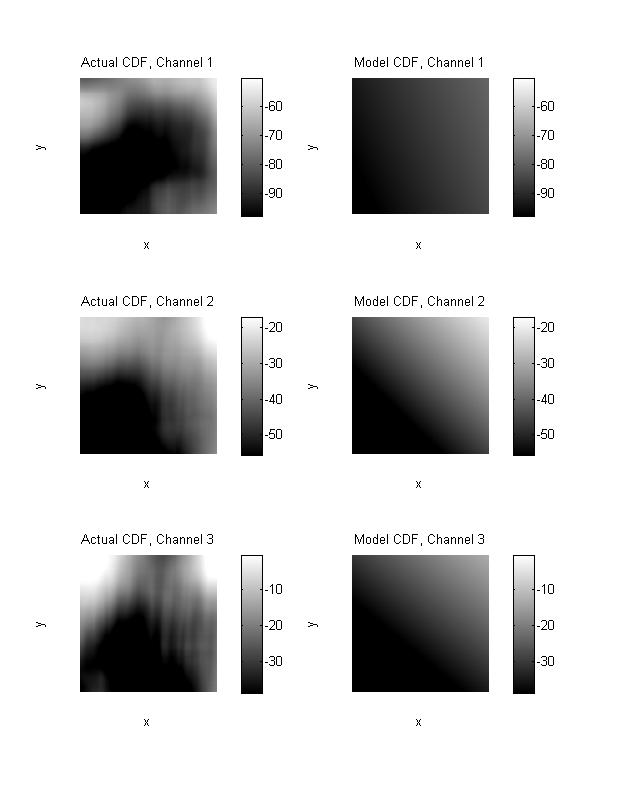

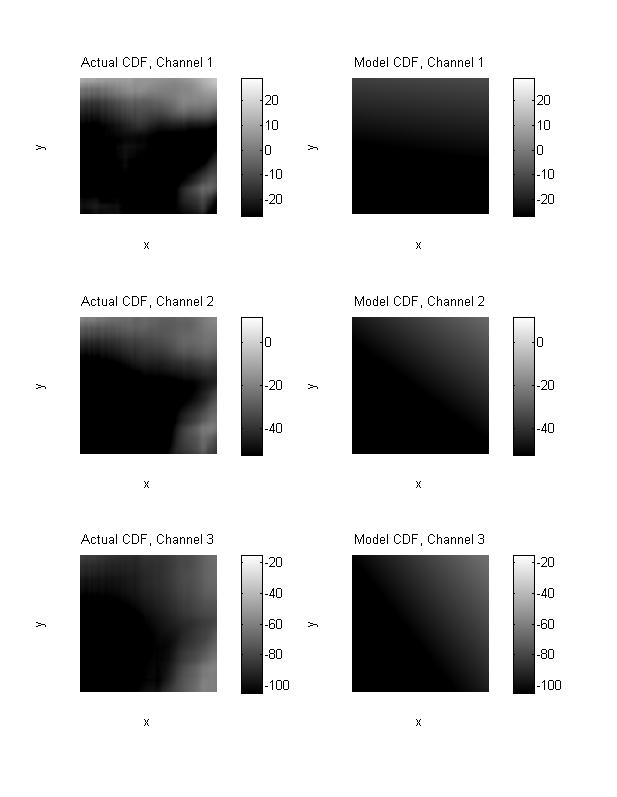

Table 1: Average (over 50 query images) normalized MSE in RGB and LAB spaces. From the plots in Fig. 11 and 12 and Table 1, we can clearly observe that both restoration models reduce the MSE on average. In particular, the linear RGB model consistently reduces the MSE, resulting in lower MSE in RGB space for 49 of 50 query images. The linear CIELAB model also works well but is less effective than the linear RGB model. Due to its low complexity and excellent performance, the linear RGB model is the preferred technique. We can also directly compare the actual CDF to the model CDF. Fig. 13, 14, and 15 plot the CDF's for the previously shown query images. In each case, the linear model accurately predicts the large-scale patterns in the actual CDF.

V. Conclusion Robust features like SIFT or SURF enable very accurate matching of a query CD cover, captured on a camera-phone, to a corresponding database CD cover stored on a remote server. Once the correct match is established, strong feature correspondences can be further used to sample the color difference function which characterizes the color differences between query and database CD covers. From the color samples, we can estimate the entire color difference function if we assume a linear model. This linear restoration technique works well in practice, giving significant subjective visual improvement and objective MSE reduction in the color-corrected query CD covers. The proposed method has low complexity and low transmission cost. Due to its efficient reuse of features originally intended for image matching, our method can be easily inserted into any feature-based recognition system. Color restoration then is another novel application in the growing field of MAR. I thank Prof Brian Wandell, Joyce Farrell, Manu Parmar, and Christopher Anderson for their helpful advice and enjoyable teaching. VI. Appendix Source Code initializeExperiment.m Sets the proper global variables. SURF/generateDatabaseFeatures.m Extracts SURF features from all database images. SURF/generateQueryFeatures.m Extracts SURF features from all query images. SURF/matchQuery.m Match query images to top database candidates. SURF/plotMatch.m Plots the results of SURF matching. SURF/ratioTest.m Finds the number of features between two feature sets which pass the ratio test. SURF/SURFPairwiseMatchFeatureSets.m Matches two feature sets by ratio test and RANSAC. SURF/createSURFFile.m Creates a SURF file from an input image. SURF/loadSURFFile.m Loads data of a SURF file into memory. SURF/showQuerySURFLines.m Shows the geometric SURF correspondence between query and database images. color/restoreQuery.m Restores all query CD covers using different models. color/restoreCD.m Restores a single CD using different models. color/projectQuery.m Projects query CD covers into rectified squares. color/projectCD.m Projects a single CD cover into a rectified square. color/measureRestore.m Measures restoration quality of color-corrected CD covers. color/rgb2xyz.m Converts from RGB to XYZ coordinates assuming some standard monitor phosphors. color/xyz2rgb.m Converts from XYZ to RGB coordinates assuming some standard monitor phosphors. helpers/listDir.m Lists the contents of a directory. helpers/printTitle.m Prints the given string within a header section. helpers/readGroundTruthData.m Reads ground truth data from a text file. SURF/showSURF.m Show SURF feature vectors laid on top of source image. ETH-SURF-Linux Linux C++ project for SURF from Herbert Bay, ETH Computer Vision Lab. ETH-SURF-Windows Windows C++ project for SURF from Herbert Bay, ETH Computer Vision Lab. SIFT Collection of SIFT scripts from Andrea Vedaldi, UCLA Vision Lab. RANSAC Collection of RANSAC scripts from Gabriel Takacs and Vijay Chandrasekhar, Stanford Information Sytems Lab. isetUtility Collection of imaging scripts from Psych 221 tutorials. VII. References [1] G. Takacs, V. Chandrasekhar, N. Gelfand, Y. Xiong, W.-C. Chen, T. Bismpigiannis, R. Grzeszczuk, K. Pulli, and B. Girod, “Outdoors Augmented Reality on Mobile Phone using Loxel-Based Visual Feature Organization,” submitted to IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. [2] D. Lowe, “Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints”, International Journal of Computer Vision, 60, 2, pp. 91-110, 2004. [3] H. Bay, T. Tuytelaars, and L. V. Gool, "SURF: Speeded Up Robust Features", Ninth European Conference on Computer Vision, Springer LNCS volume 3951, part 1, pp 404-417, 2006. [4] C. Harris and M. Stephens, "A combined corner and edge detector", Fourth Alvey Vision Conference, Manchester, UK, pp. 147-151, 1988. [5] M. A. Fischler and R. C. Bolles, "Random Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography", Communications of the ACM 24, pp. 381–395, June 1981. [6] B. Wandell, Foundations of Vision, Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 1995. [7] M. Chambah and B. Besserer, "Digital Color Restoration of Faded Motion Pictures", International Conference on Color in Graphics and Image Processing, Saint-Etienne, France, pp. 338-342, 2000. [8] X. Li, D. Lu, and Y. Pan, "Color Restoration and Image Retrieval for Dunhuang Fresco Preservation", IEEE Multimedia Magazine, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 38-42, June 2000. [9] M. Pappas and I. Pitas, "Digital Color Restoration of Old Paintings", IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 291-294, February 200. |

|

|

|