Localized Noise Power Spectrum Analysis

PSYCH 221: Applied Vision and

Image Engineering – class project

Adam Wang

20 March 2008

Table

of Contents

1.

Introduction

2.

Motivation

3.

NPS Review

4.

Methods

5.

Results

6.

Conclusion

7.

References

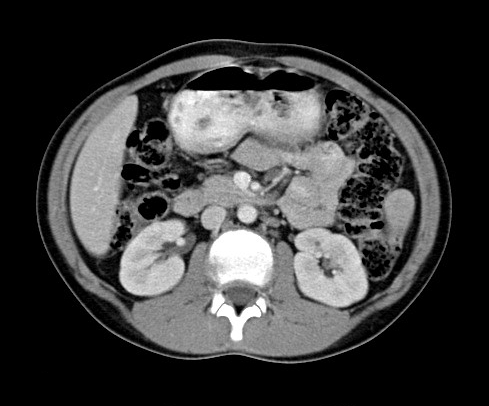

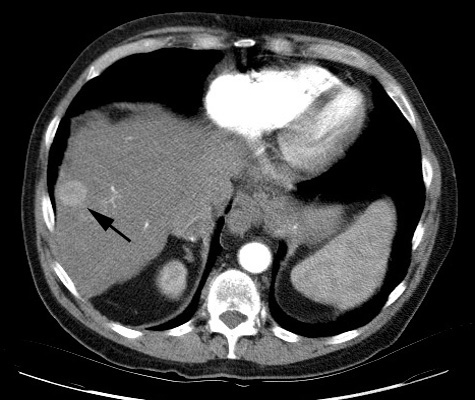

Since the 1970s, computed tomography (CT) has

revolutionized medical screening, diagnostics, and treatment with its ability

to non-invasively image the human body. Figure 1 shows a typical CT image of a

human abdomen [1] and clearly illustrates structures such as the liver,

kidneys, and spine.

Figure 1. Typical abdomen CT image.

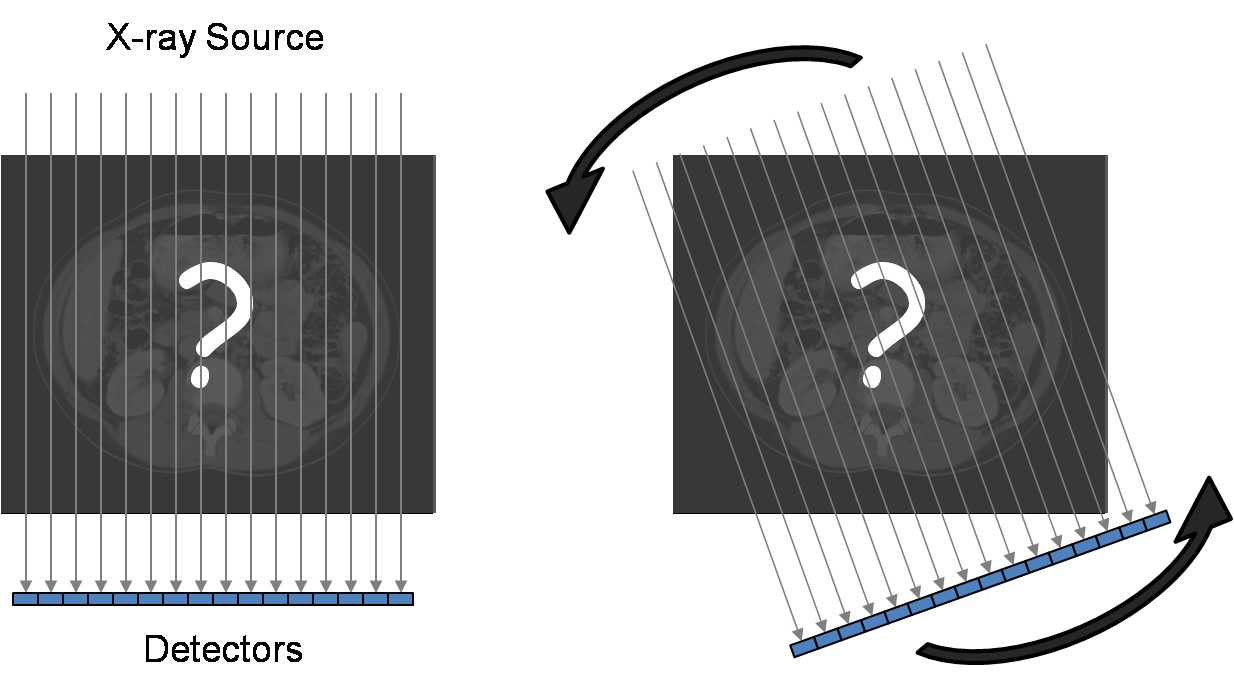

If we are given an unknown object, such an image

cannot be measured or produced directly; instead a series of x-ray measurements

are acquired. Assuming a parallel beam geometry for simplicity, Figure 2a

illustrates one set of measurements called a single view of the object. A

parallel set of x-rays pass through the object, and the x-ray intensities that

are transmitted through the object are measured by an array of detectors. This

is repeated for multiple views as the source and detectors rotate around the

object (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. CT data acquisition.

The resulting data is referred to as the raw data

and as the sinogram when displayed.

Figure 3. Reconstruction algorithms convert raw data

(sinogram) to an image of the object.

Each row of the sinogram is the detector

measurements from one view. We can clearly see sinusoidal patterns in the

sinogram (hence the name) because the source and detector are rotating about

the object. This raw data must be reconstructed using standard CT

reconstruction algorithms [2] to produce images of the unknown object.

Recent trends in CT such as faster and more

detectors and multiple sources are increasing the raw data size and rate during

an acquisition so much that current data transmission systems may become a

bottleneck. Furthermore, after a reconstruction engine forms a reconstructed

image from the raw data, it is soon discarded, and any additional information

contained within the raw data is lost. While lossy compression of the raw data

is a solution to both problems by reducing the data size so that data

transmission and storage is easier, it introduces errors into the raw data, and

thus the reconstructed image. This is important because errors or noise can

adversely affect the diagnostic value of CT images.

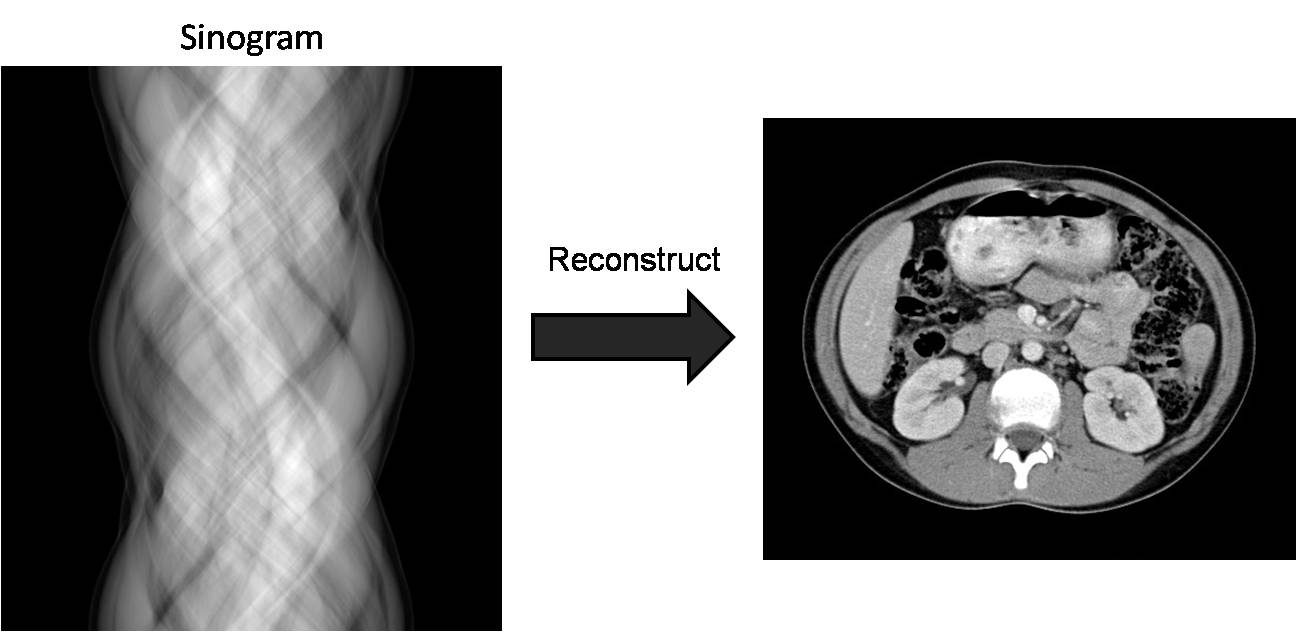

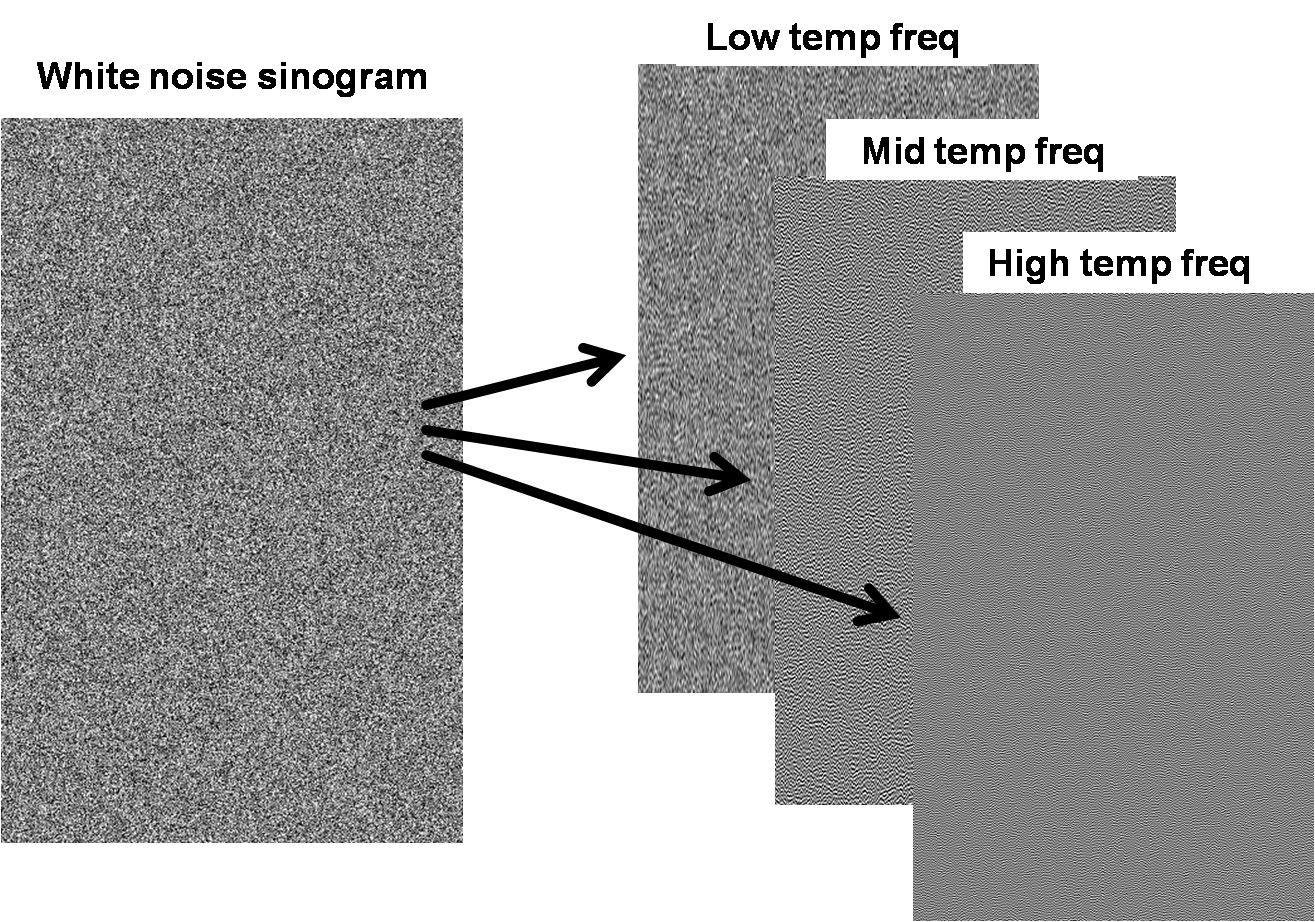

In general, it is appropriate to consider noise in

CT images as additive CT noise originating from additive white noise in the

sinogram. This is also an appropriate first-order model for errors introduced

by compression of the raw data, so we will use the terms “error” and “noise”

interchangeably. However, since we have the freedom to choose our compression

technique, we can target and control what types of errors we introduce into the

raw data. One such consideration is the temporal frequency (vertical direction

in the sinogram) of the errors we introduce. Without too much loss of

generality, we consider low, middle, and high frequencies in this direction,

while allowing for all frequencies in the horizontal direction (detector

spatial frequency).

Our previous work [3][4] has shown that this

consideration is significant because errors in the low temporal frequencies

reconstruct as errors in the center of the image (actually, field of view),

whereas errors in the high temporal frequencies reconstruct as errors in the

periphery of the image. We consider the latter case to be an improvement over

the former because most imaging tasks rely much more heavily on the center of

the image. Therefore, not all errors have the same impact, and although it can

be extremely difficult to quantify, we claim that some sinogram errors can be

thought of as better than others because of their effect on the reconstructed

image.

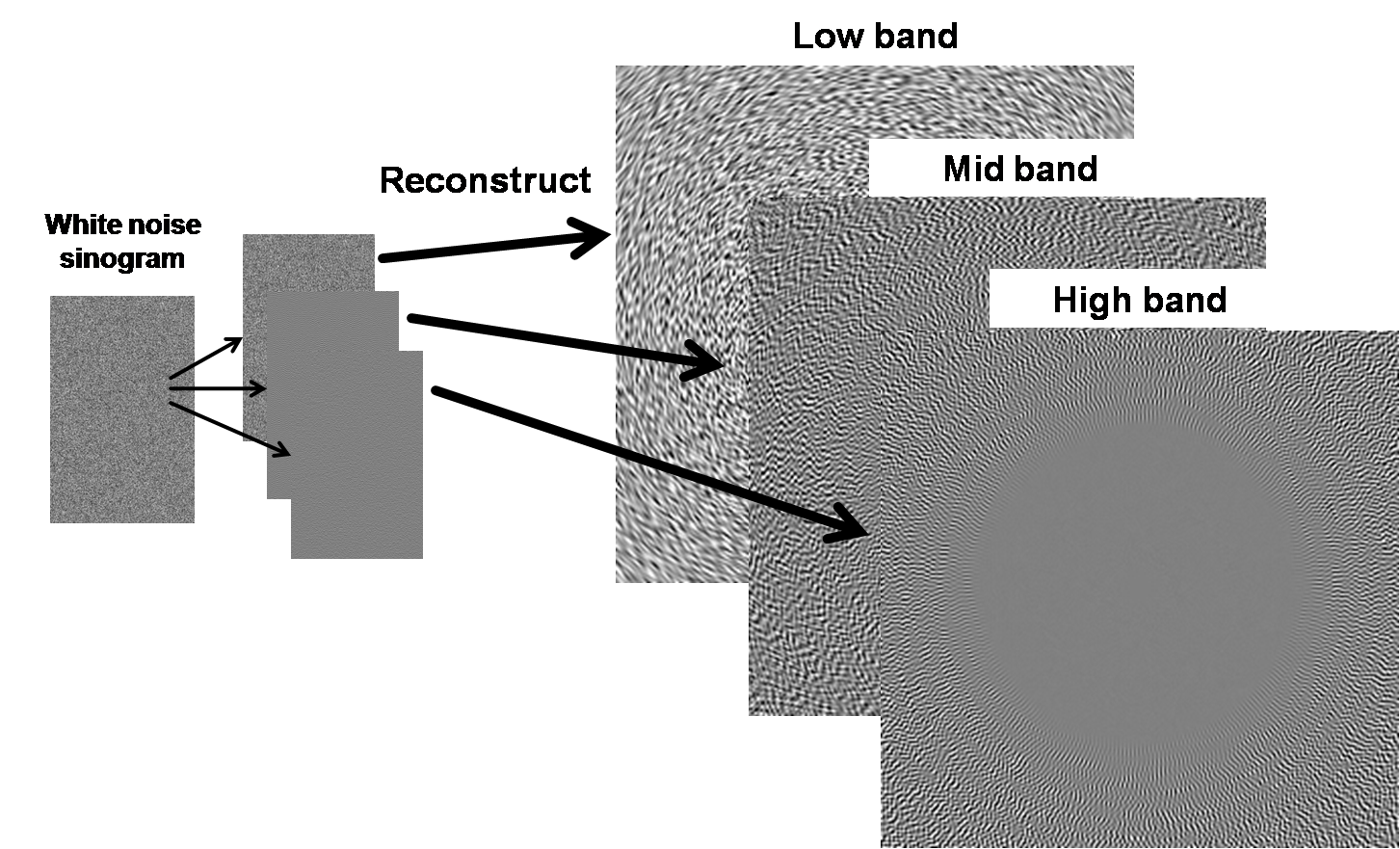

To prevent confusion with all the other frequencies

that will be discussed, we introduce some simplified terminology. A white noise

sinogram can be decomposed into a sum of its low, middle, and high temporal

frequencies (lowest 1/3, middle 1/3, and highest 1/3 of all frequencies up to

the Nyquist frequency, respectively).

Figure 4. Decomposing white noise into different bands of

vertical frequencies.

Each band can be reconstructed independently to form

what we will call low, middle, and high band images.

Figure 5. Reconstructing different bands.

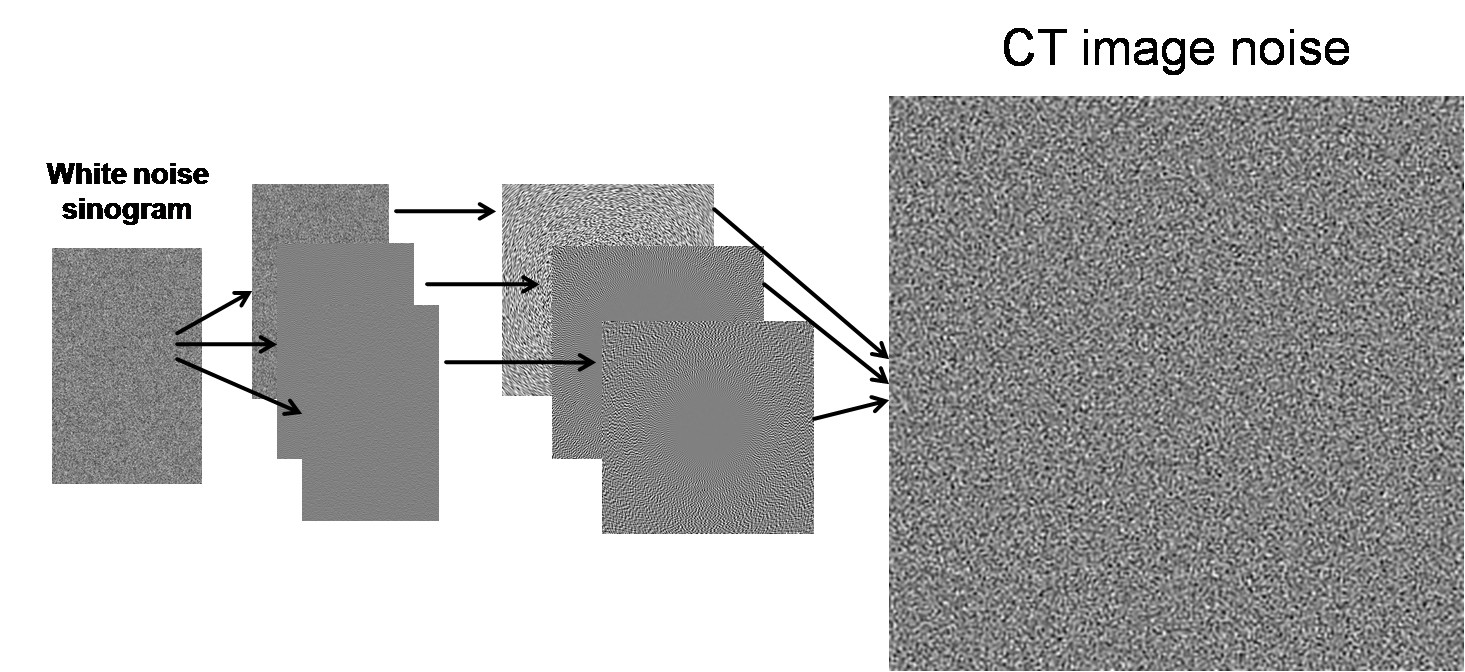

Since reconstruction is a linear process, the sum of

these images is equivalent to the reconstructed image of the original white

noise sinogram, and we can consider noise images independently of the object

being imaged because the noise is additive.

Figure 6. Overall diagram of breakdown of errors into low, middle,

and high bands.

While our previous work analyzed the spatial

dependence of the magnitude of these CT image errors for the low, mid, and high

bands, we have yet to analyze the spatial dependence of the frequency content of

the CT image errors for the various bands. We believe that this could also

determine what types of errors (low, mid, or high band) have the greatest

(negative) impact on the reconstructed image.

Consider a (real) signal g(t) and its Fourier

transform G(f). Then its power spectrum is defined as P(f) = |G(f)|2.

By Parseval’s theorem, the energy of the signal, ![]() , is equivalent to the area under the power spectrum curve,

, is equivalent to the area under the power spectrum curve, ![]() . If our signal is zero-mean noise, we can think of energy as

the mean-squared error (MSE). For a 2D signal or image, g(x, y), we simplify the power spectrum analysis by only considering P(ρ),

where

. If our signal is zero-mean noise, we can think of energy as

the mean-squared error (MSE). For a 2D signal or image, g(x, y), we simplify the power spectrum analysis by only considering P(ρ),

where ![]() and G(kx, ky) is the 2D Fourier transform of g(x, y).

and G(kx, ky) is the 2D Fourier transform of g(x, y).

If a signal gw(t) is white noise, then its values at

different time points are completely uncorrelated. In other words, in order to

generate a zero-mean white noise signal, we take independent realizations of

zero-mean identical distributions, such as a zero-mean normal distribution. The

power spectrum of white noise is constant: Pw(f) = c.

Since power spectrum is a function of (signal) frequency, its equivalent color

can be described as if P(f) were a light wavelength distribution

as a function of (light) frequency [5]. Therefore, if P(f) is flat, it has

power at all wavelengths and is thus called “white”.

Filtering gw(t) with h(t) produces a noise

signal with Fourier transform H(f)Gw(f), so its power spectrum is P(f)

= |H(f)|2|Gw(f)|2 = c |H(f)|2.

Therefore, |H(f)|2 determines the shape of the noise power spectrum

(NPS) and any desired NPS can be achieved by filtering white noise (createNoise.m).

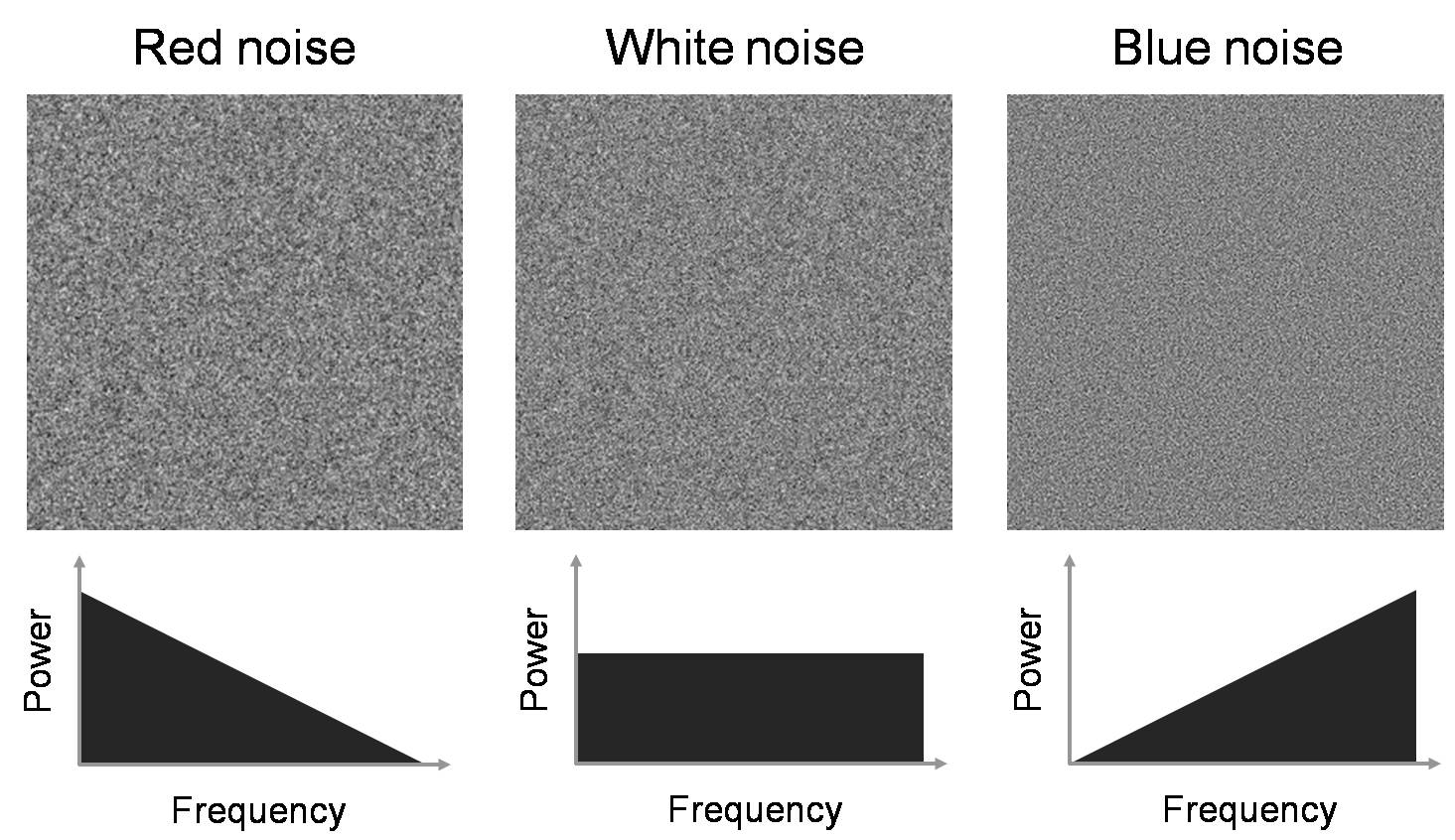

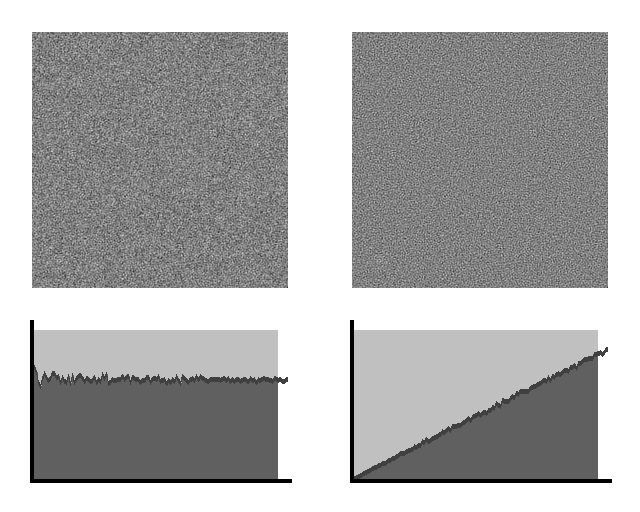

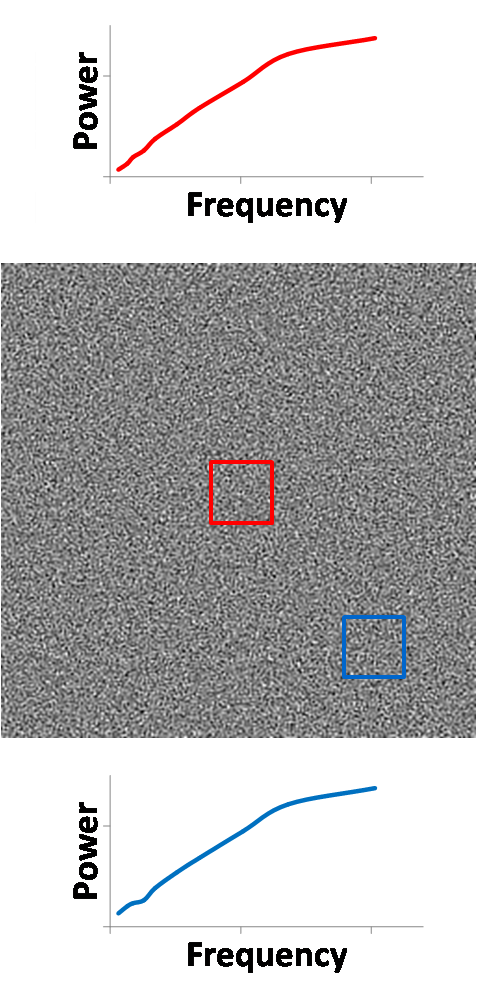

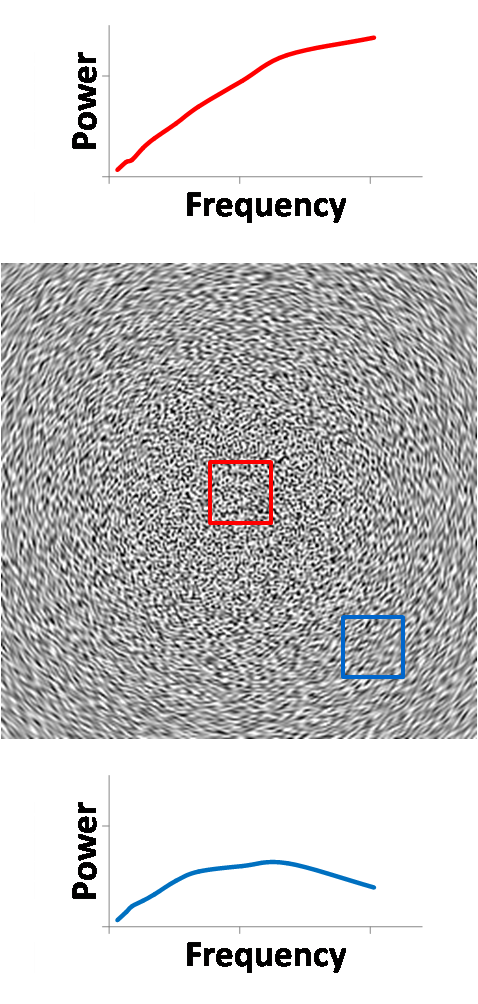

Figure 7 illustrates three types of common noise

colors and their noise power spectra. All three images have the same noise

energy, but have different NPS characteristics. Red noise is dominated by low

frequency noise (analogously, red light is dominated by long wavelength, or low

frequency, photons), and blue noise is dominated by high frequency noise (blue

light is dominated by short wavelength, or high frequency, photons). As we will

see later, noise in a CT image resembles blue noise.

Figure 7. Images of colored noise and their associated noise

power spectra.

We first confirm that the color of noise can impact

the detectability of objects in an image dominated by noise. One of the common

tasks of radiologists using CT is to identify tumors, such as the one in Figure

8, annotated by a black arrow [6]. The tumor is a small round object that is

slightly brighter than the background liver tissue. Because it is not texture

but a uniform increase in signal that defines the tumor, it consists of mostly

low frequencies. Therefore, filtering away high frequencies would not

significantly reduce the visibility of the tumor, but it could filter away

undesired noise. To test the difference this has on different colors of noise,

we “hide” a tumor-like object in a uniform background by injecting enough white

or blue noise so that the object is lost among the noise. A video was created

in Matlab to illustrate our ability to find this tumor as the image is

increasingly blurred by a low-pass filter (createNoiseMovie.m).

Figure 8. Subtle liver tumor.

Matlab’s Signal Processing Toolbox enables us to

simulate raw data acquisition and image reconstruction. However, Matlab’s

reconstruction algorithm uses interpolation methods (nearest-neighbor, linear,

etc) that limit the frequency response of the reconstructed image, so this has

been modified to perform ‘sinc’ interpolation (iradon2.m).

We examine several methods for evaluating localized

noise power spectra – the noise characteristics in a small region of interest

of an image. The simplest method to analyze frequency content as a function of

space is a Short-Term Fourier Transform (STFT), which performs a Fourier

transform of a small window around any spatial location. We also implement and

investigate the newly developed Stockwell Transform, which gives the

instantaneous frequency response for every single point in a signal. Finally,

we apply the Wavelet Transform, which enables us to nicely visualize any

spatially-dependent noise power spectrum.

The 2D Stockwell transform of image g(x,

y) is defined as ![]() [7]. Therefore, for

all points (x, y) in the image, we get the full instantaneous spectrum (kx, ky). The term

[7]. Therefore, for

all points (x, y) in the image, we get the full instantaneous spectrum (kx, ky). The term ![]() can be thought of as a

Gaussian window that changes position with spatial location (x, y)

and shape with spatial frequencies (kx,

ky), while the

can be thought of as a

Gaussian window that changes position with spatial location (x, y)

and shape with spatial frequencies (kx,

ky), while the ![]() term is just the normal 2D Fourier transform. One nice

property about the Stockwell transform is that its integral over all of space

yields the 2D Fourier transform:

term is just the normal 2D Fourier transform. One nice

property about the Stockwell transform is that its integral over all of space

yields the 2D Fourier transform: ![]() . The 1D and 2D discrete versions of the Stockwell transform

were implemented as described in [8] and [9], respectively (st1d.m, st2d.m).

. The 1D and 2D discrete versions of the Stockwell transform

were implemented as described in [8] and [9], respectively (st1d.m, st2d.m).

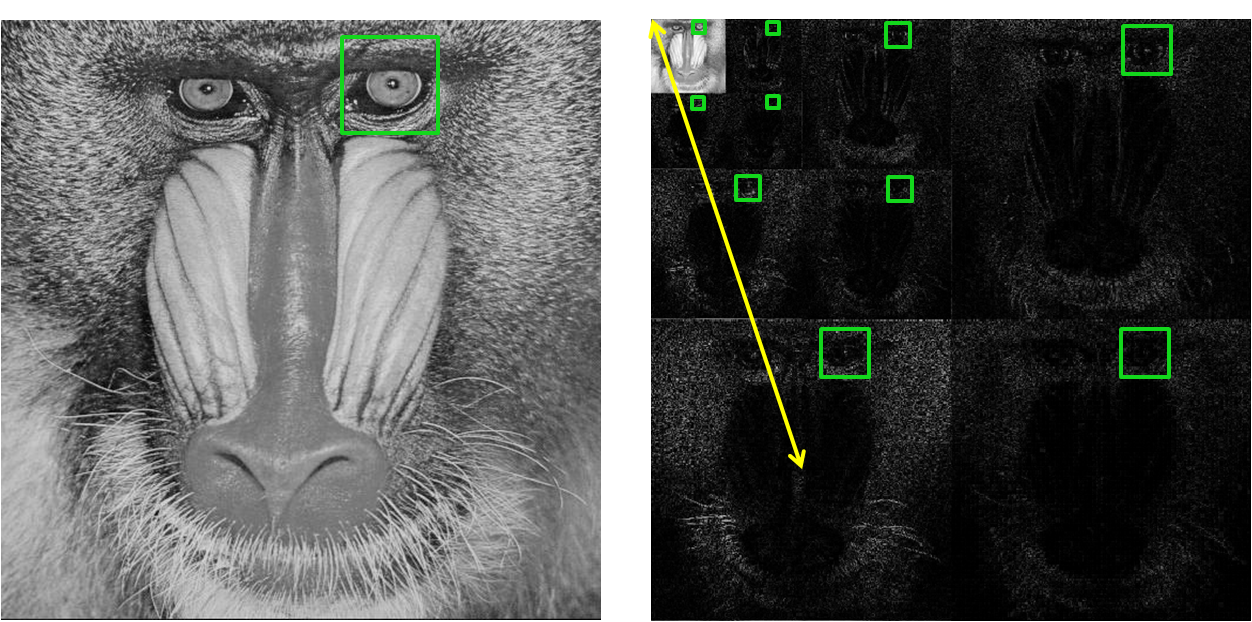

While the STFT and Stockwell Transform are useful

tools, neither directly enables the simultaneous visualization of both space

and frequency of a 2D image since they produce 4D data (2D frequency as a

function of 2D space). All data from a wavelet decomposition, on the other

hand, can be arranged to illustrate both space and frequency in an easy-to-read

fashion, as described by the mandrill example below. When the coefficients of

the wavelet transform are displayed in the manner, the subblocks in the top

left correspond to lower frequencies whereas the subblocks toward the bottom

correspond to higher vertical frequencies and those toward the right correspond

to higher horizontal frequencies.

Figure 9. Mandrill image (left) and its 3-level 2D wavelet

decomposition (right).

To perform localized NPS analysis with the

Daubechies wavelet transform, we first take the square of the wavelet

coefficients to get “wavelet power”. Since the sum of the wavelet power is

equivalent to the image energy [10], this is an appropriate equivalent to the

power spectrum in Fourier space. Each subblock of the wavelet power is a scaled

and filtered version of the image, so if we consider a region of interest in

the image with a square window of size Ws

= 2n, then we can do an n-level 2D wavelet decomposition where

each subblock has a corresponding window for the region of interest in the

image. This is illustrated in the above figure, where our region of interest is

the mandrill’s left eye. The window size of each subblock is Ws/2level # and is

centered on the mandrill’s left eye in each subblock. We consider the

representative frequency of each subblock to be proportional to the distance

from the top left corner to the center of the subblock, as shown by the yellow

line for the bottom left subblock. To create a local NPS profile, we plot the

average power in each scaled window against the representative frequency of the

window’s subblock. This was implemented in NPS_ROI.m.

To obtain a good representation of wavelet power, we

averaged the wavelet power of 200 realizations of CT noise, low band, mid band,

and high band reconstructed images. For each realization, a white noise

sinogram was generated and then reconstructed. Similarly, the white noise

sinogram was filtered by each of the low, mid, and high bands, and each was

reconstructed.

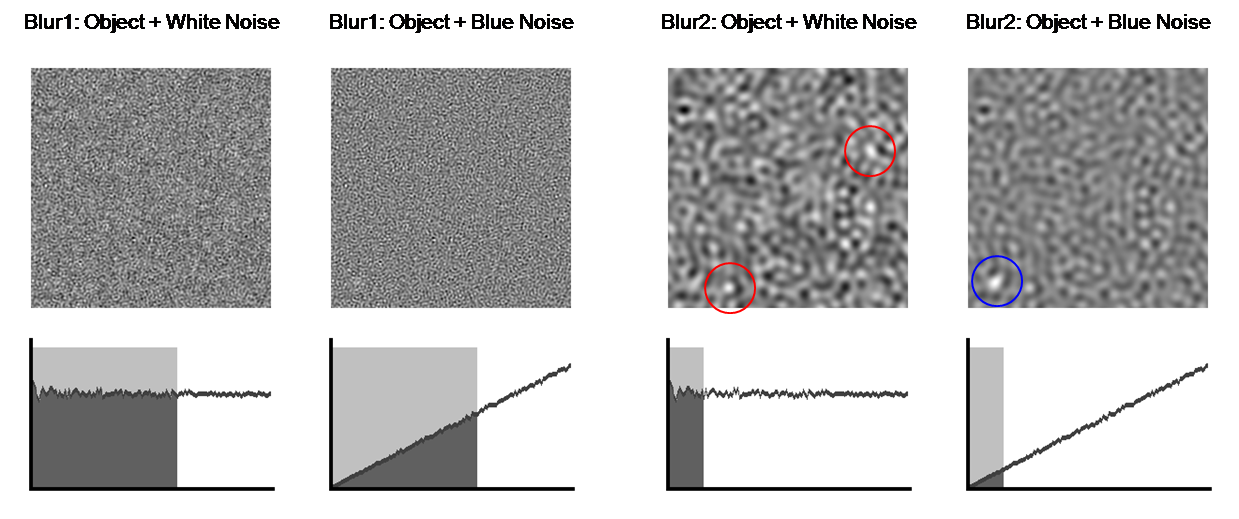

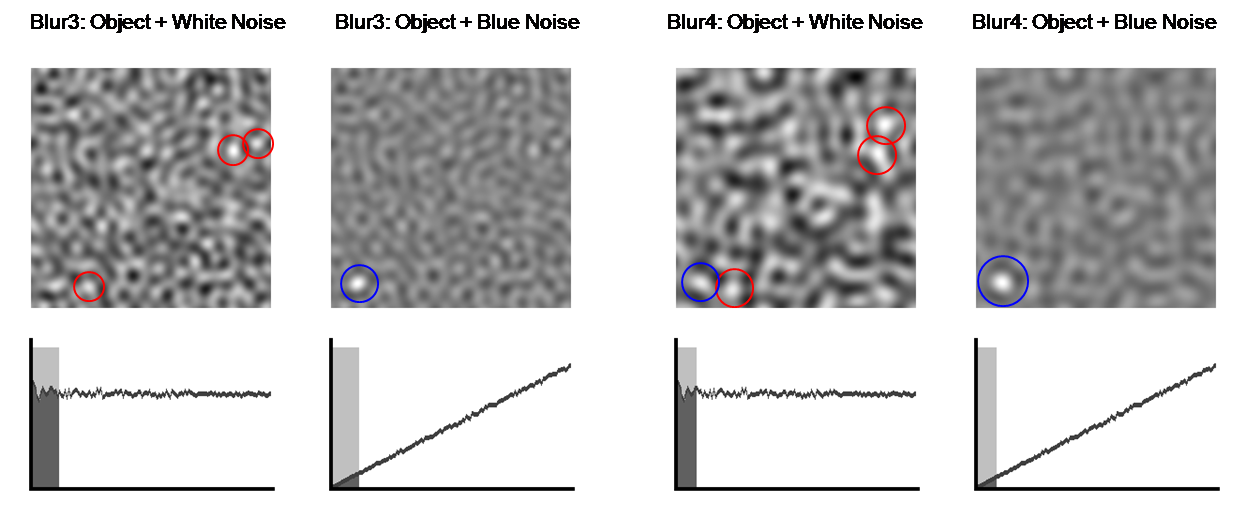

We start with a tumor-like object that is brighter

than a uniform background.

Figure 10. Simulated tumor.

Then we add either white noise or blue noise with

the same energy to the image.

Tumor +

White Noise Tumor

+ Blue Noise

Figure 11. Simulated tumor masked by white (left) and blue

(right) noise.

As we begin to blur the image with a low-pass

filter, we can see that the amount of noise decreases until the tumor hidden by

the blue noise becomes apparent. Because most of the tumor’s energy is in low

frequencies, it still remains in the image as we filter away noise. The plots

of NPS make it clear that low-pass filtering is much more advantageous for

removing blue noise than white noise. No amount of blurring can help us find

the object in white noise because the NPS is flat, whereas blurring enables us

to find the tumor in blue noise. While the tumor is present in all of the

filtered white noise images, numerous ambiguities exist in the tumor-detection

task. Therefore, for such tasks, having blue noise is better than having white

noise because most of the blue noise power is in the higher frequencies.

Figure 12. Blurring makes tumor detection easier. The blue

circles indicate the correctly identified tumor, whereas the red circles

indicate multiple ambiguities.

Despite its use by some groups analyzing medical

images [9], our results show that the Stockwell transform has some flaws when

applied to noise. For simplicity, we only consider the 1D Stockwell transform,

although the same results hold for the 2D Stockwell transform.

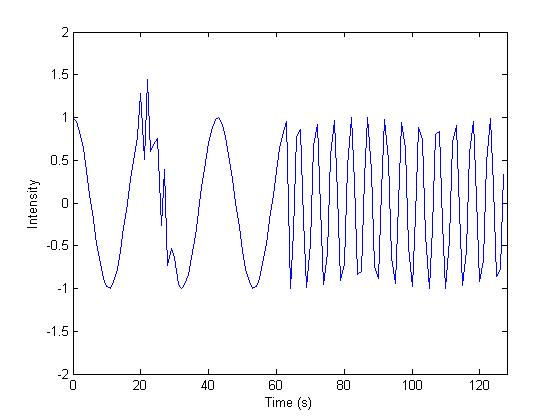

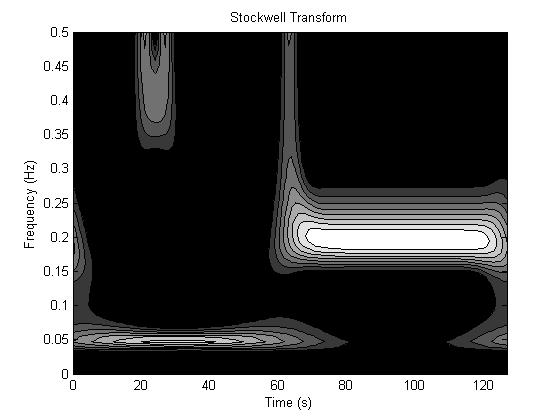

First, we demonstrate that the Stockwell transform

is a valid approach to general time-frequency analysis. Consider the signal

below on the left, which is characterized by a low frequency sinusoid (f = .05 Hz) in the first half and a high

frequency sinusoid (f = .2 Hz) in the

second half. There is also a burst of high frequency (f = .4 Hz) between time t

= 20s and t = 30s. The magnitude of

its (complex) Stockwell transform is on the right, clearly showing excellent

agreement with the description of the signal and a sharp differentiation of the

different frequency components.

Figure 13. Stockwell transform (right) of time signal (left).

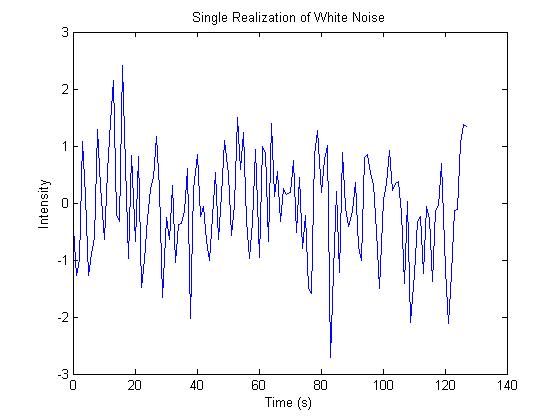

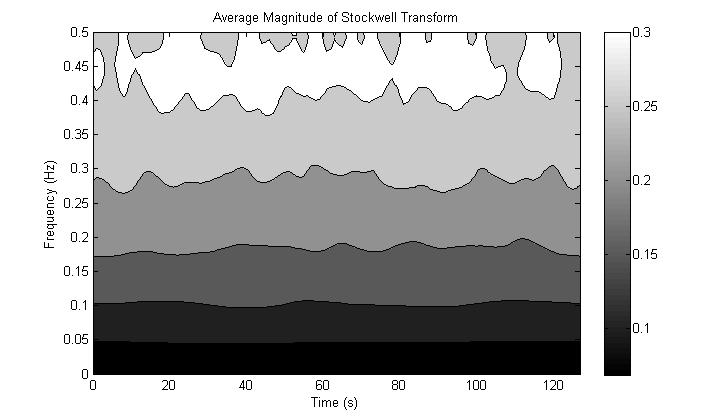

However, if we try to apply the Stockwell transform

to white noise, the result is not useful for our purposes. To illustrate this

we average the magnitude of the Stockwell transform of 1000 realizations of

white noise. We would like to see the frequency spectrum to be flat for each

time point, and thus constant for the entire image representation, but instead

we get a drop-off at lower frequencies. This drop-off is caused by the Gaussian

windowing term that can be better understood if we express the Stockwell

transform as ![]() . Here, G(kx, ky) is the Fourier transform of the image g(x,

y). The Gaussian term

. Here, G(kx, ky) is the Fourier transform of the image g(x,

y). The Gaussian term ![]() always has a maximum height of 1, but broadens with larger (kx, ky) and narrows to an impulse as (kx, ky)

ŕ 0. The

always has a maximum height of 1, but broadens with larger (kx, ky) and narrows to an impulse as (kx, ky)

ŕ 0. The ![]() term is the inverse Fourier transform of the

shifted Fourier transform. Therefore, for higher frequencies, the broad

Gaussian term has more area under its curve than for lower frequencies, so the

Stockwell transform will have higher signal at higher frequencies than lower

frequencies. This drop-off does not exist for the STFT or Wavelet transform

because the coefficients of white noise decomposed into orthonormal components

will also be white.

term is the inverse Fourier transform of the

shifted Fourier transform. Therefore, for higher frequencies, the broad

Gaussian term has more area under its curve than for lower frequencies, so the

Stockwell transform will have higher signal at higher frequencies than lower

frequencies. This drop-off does not exist for the STFT or Wavelet transform

because the coefficients of white noise decomposed into orthonormal components

will also be white.

Figure 14. Stockwell Transform of white noise does not produce

a flat spectrum.

Further difficulties were encountered with the 2D

Stockwell transform due to its immense memory and computational requirements.

Because the implementation requires O(N4) memory and O(N4logN) computation time for a NxN

image [9], images beyond size 100x100 could not be reasonably handled by normal

PCs. Even our sub-sampled implementation of the 2D Stockwell transform,

although cutting down on the memory requirements, still required the same

computation time. Therefore, it was decided that the Stockwell transform was

not a reasonable approach for our problem. Nonetheless, the 1D, 2D, and 2D

sub-sampled Stockwell transforms were implemented in Matlab, and their code is

included in the Appendix (st1d.m, st2d.m, st2d_sub.m, st_example.m).

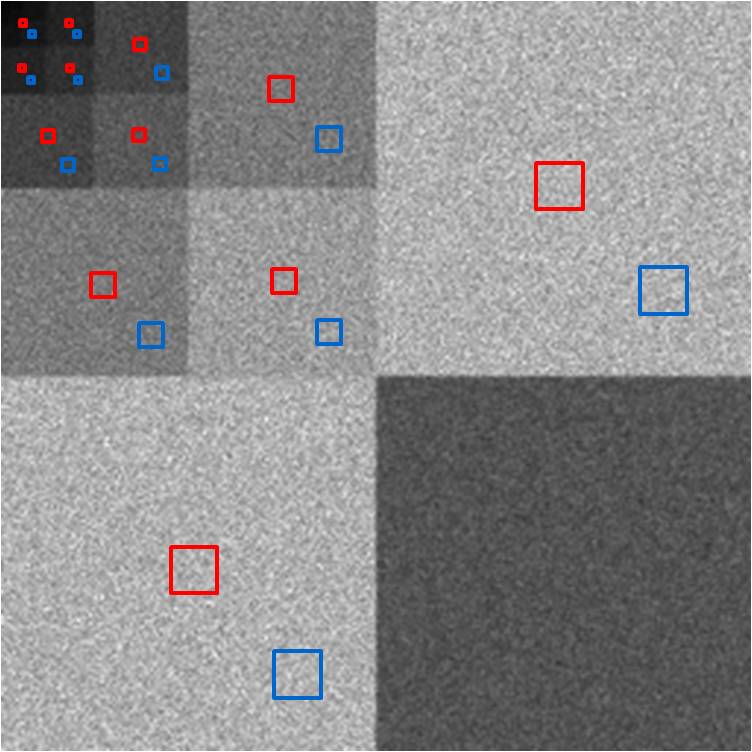

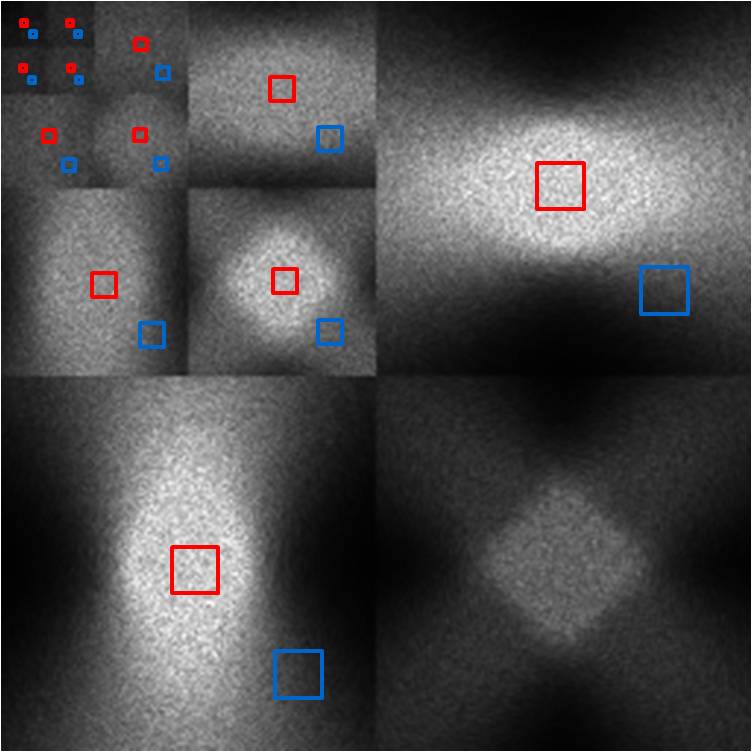

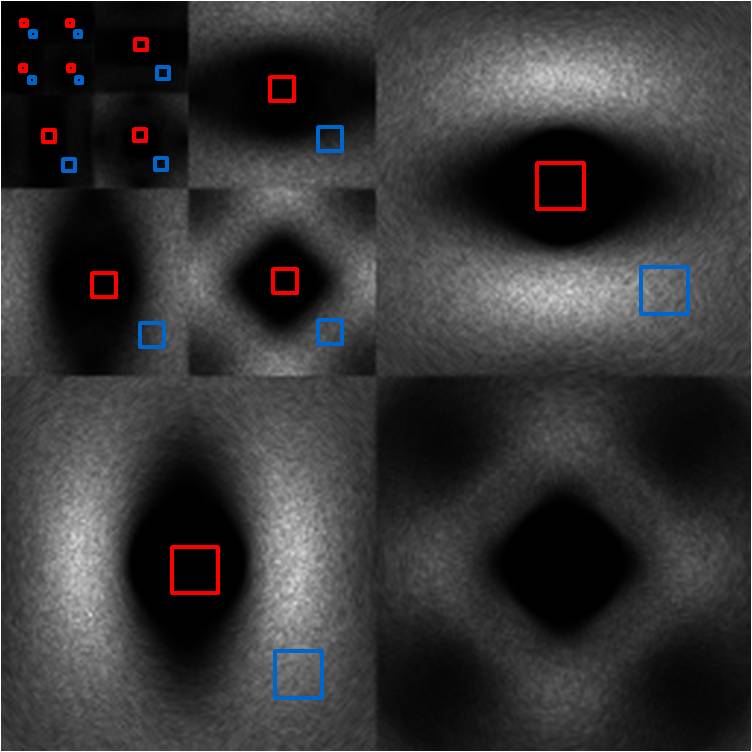

In the figure below, the left image is one realization

of CT noise. The right image is the average wavelet power over 200 realization

of CT noise. We ignore the highest frequency subband of the wavelet transform

(lower right block) because its frequencies are primarily outside the frequency

response of the CT reconstruction algorithm. The wavelet power very nicely

shows us that within each subblock, the frequency response is constant across

the image, and that decreasing frequencies (moving up and left) have less

wavelet power. If we take a region of interest (ROI) in the center denoted by

the red window, we see that the NPS in that region is as we expect, like blue

noise. An edge ROI denoted by the blue window produces a similar NPS, showing

that the NPS is stationary across the image. All NPS plots are shown on the

same scale, unless indicated otherwise.

CT Noise

Figure 15. Wavelet power (right) of CT noise (left) enables

localized NPS analysis.

Our results become more interesting when we examine

the three bands of noise. The wavelet power image demonstrates that the low

band’s noise energy is primarily in the center of the image. In fact, the red,

center ROI of the image shows that the NPS at the center of the low band image

is much like CT noise in shape and power levels. However, at the blue, edge

ROI, the local NPS has lost much of its high frequency content, while it still

has just as much low frequency noise. While less high frequency noise is good,

we still have the low frequency noise, which as shown before, is a bigger

problem for tumor-detection tasks. If we look at the periphery of the low band

noise image, we see blurring in the radial direction, and this is captured well

in the wavelet power. For instance, at the top center of the image, the

blurring is primarily in the horizontal direction, and we see this as a void of

energy at the top center of the top right subblock of the wavelet power image,

whereas there is still substantial energy in the vertical direction, as shown

at the top center of the bottom left subblock of the wavelet power image.

Low Band

Figure 16. Wavelet power (right) of low band image (left).

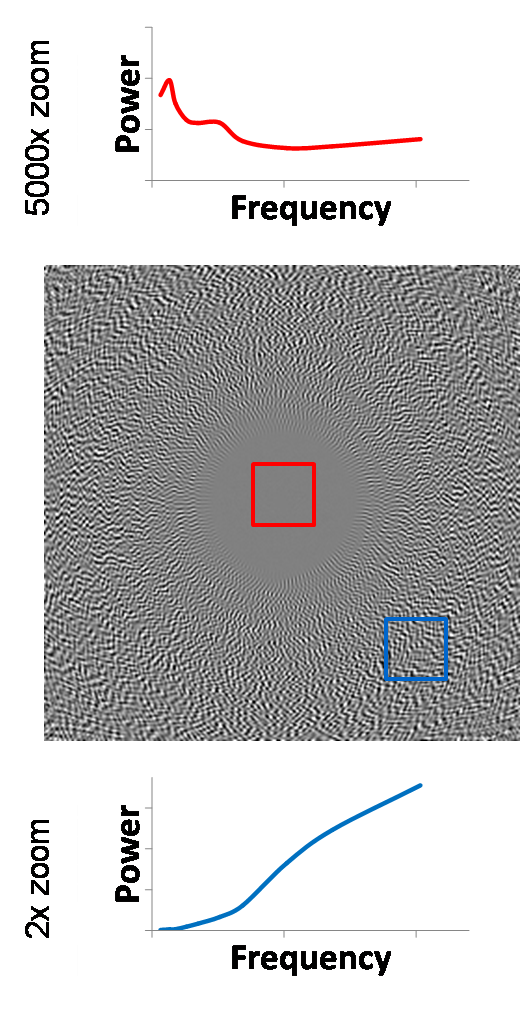

The reconstructed image of mid band noise has a characteristic

void of noise energy in the center region. This manifests itself very clearly

in the wavelet power image, as all subblocks demonstrate this void in the

center. Nonetheless, there is still some energy at the center, and after

magnifying the power scale by 5000x, we see that the shape of the spectrum is

far from blue noise. However, the sheer magnitude of suppression of noise

energy in this region mitigates any such concern. At the edge region, the local

NPS shows that overall noise power is scaled down by a factor of 2 and is more

“blue” than CT noise in the sense that its spectrum is more dominated by higher

frequencies.

Mid Band

Figure 17. Wavelet power (right) of mid band image (left).

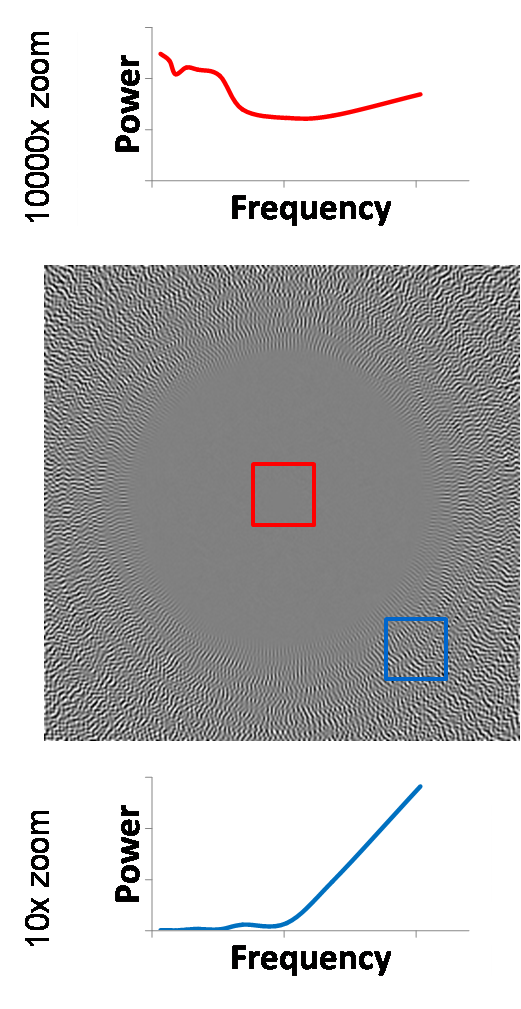

The high band noise is an even more extreme version

of the mid band noise. The central void is even larger, and the edge NPS is

even more highly concentrated in the high frequencies. This is very apparent in

the wavelet power image, which shows that the noise power cannot be seen after

the second-level decomposition. Thus, low frequency noise is not significant

throughout the entire image, and the only noise we have (if any at all) is high

frequency.

High Band

Figure 18. Wavelet power (right) of high band image (left).

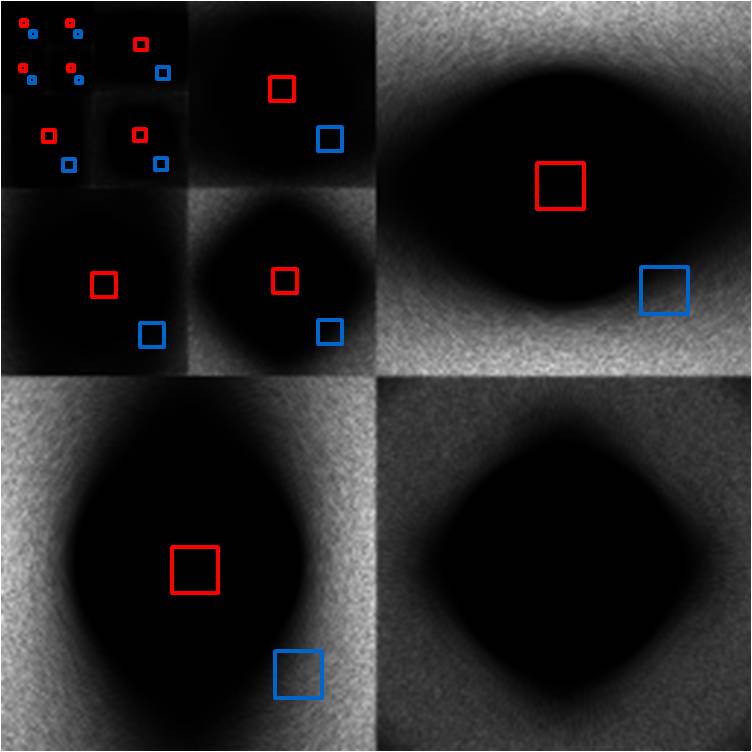

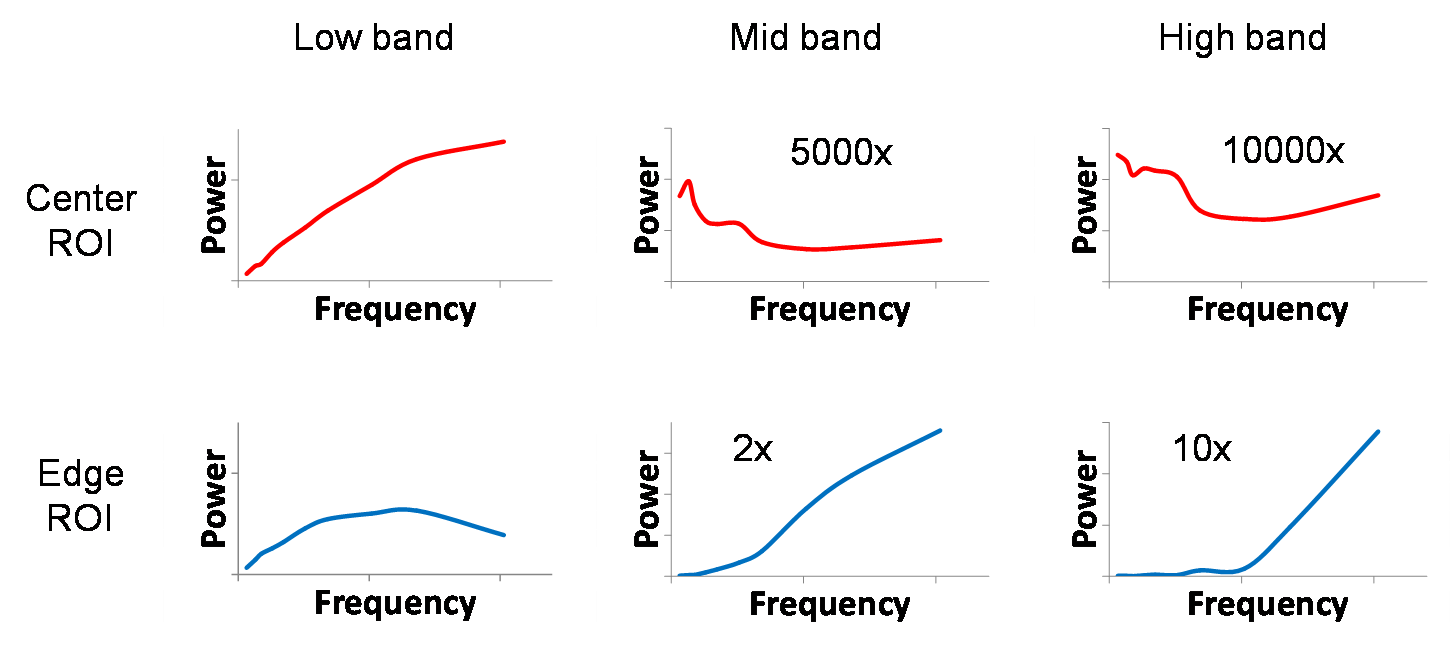

The final comparison of the images from the low,

mid, and high bands at a center ROI and an edge ROI is shown below. Our

previous work has already shown the increasing void in the center of the image as

we move to higher bands. Again, this is seen as beneficial because usually the

clinical region of interest is at the center of the image, not at the edge. But

we now see that even if we had to sacrifice a 5-fold increase in high band

noise power to sequester the low band noise, we would not be affected in the

center of the image (2000x reduction of noise power instead of 10000x), and

although now the NPS at the edge of the high band would be on the same scale as

that of the low band, we still have the additional benefit of it being

dominated by high frequency noise.

Figure 19. Side-by-side comparison of local NPS for low, mid,

and high band images.

Our results have shown that for certain tasks such

as tumor detection, image noise color affects an ideal-observer’s performance

(whether or not a human observer would actually do better is another matter).

When doing time-frequency analysis the Stockwell transform gives a wealth of

information, but is a poor choice for both analyzing noise power spectra and

analyzing large images. The wavelet transform is useful in both visualizing and

discerning localized frequency content of noise and has shown us that higher

temporal frequencies in the sinogram (high band) are a win-win situation due to

the void of errors in the center of the image and push of noise power to higher

frequencies where the errors are significant at the edge of the image.

[1] University

of Kansas Hospital – Nuclear Medicine. http://www.rad.kumc.edu/nucmed/images/pet/lymphoma_ct_abdomen2_0304.jpg.

Accessed 17 March 2008.

[2] A.

C. Kak and Malcolm Slaney, Principles of Computerized Tomographic Imaging, IEEE

Press, 1988.

[3] A.

S. Wang, Y. Xie, and N. J. Pelc, “Effect of the Frequency Content and Spatial

Location of Raw Data Errors on CT Images,” Vol. 6913 of Medical Imaging 2008: Physics of Medical Imaging. Proc. of SPIE,

2008, in press.

[4] Y.

Xie, A. S. Wang, and N.J. Pelc, “Lossy Raw Data Compression in Computed

Tomography with Noise Shaping to Control Image Effects,” Vol. 6913 of Medical Imaging 2008: Physics of Medical

Imaging. Proc. of SPIE, 2008, in

press.

[5] Wikipedia,

“Colors of Noise,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colors_of_noise.

Accessed 12 March 2008.

[6] Radiofrequency

Ablation, Massachusetts General Hospital, “Liver Tumor Before RF Ablation,” http://www.massgeneralimaging.org/RFA_Site/NewFiles/CaseStudies.html.

Accessed 17 March 2008.

[7] L.

Mansinha, R. G. Stockwell, R. P. Lowe, M. Eramian, R. A. Schincariol, “Local

S-spectrum Analysis of 1-D and 2-D Data,” Physics

of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 103 (1997) 329-336.

[8] R.

G. Stockwell, L. Mansinha, and R. P. Lowe, “Localization of the Complex

Spectrum: The S Transform,” IEEE

Transactions on Signal Processing, Vol. 44, No. 4, April 1996.

[9] R.

A. Brown, H. Zhu, J. R. Mitchell, “Distributed Vector Processing of a New Local

MultiScale Fourier Transform for Medical Imaging Applications,” IEEE Trans. on Medical Imaging, Vol. 24,

No. 5, May 2005.

[10] I.

Daubechies, Ten lectures on wavelets,

CBMS-NSF conference series in applied mathematics. SIAM Ed (1992).

8. Appendix – Code

and Files

The following code and files are everything you need

to reproduce the work here! Support .m files and images provide further

examples on CT and image processing. All code was written by me unless

otherwise noted.

createNoise.m Code

to create the colored noise and spectra of Fig. 7.

createNoiseMovie.m Code to create movies of blurring white and blue noise that

masks an object. Figures 10-12 come from here.

iradon2.m Modified

inverse radon transform (MATLAB) to reconstruct CT images. Adds ‘sinc’

interpolation for better reconstruction frequency response.

localNPS_CTnoise.m Produces ‘Wavelet NPS Analysis’ results by generating CT

noise, low band, mid band, and high band images and finding wavelet power.

NPS_ROI.m Finds

the NPS of an ROI based on wavelet decomposition, given an image and window.

st1d.m 1D

Stockwell transform implementation.

st2d.m 2D

Stockwell transform implementation.

st2d_sub.m Sub-sampled

2D Stockwell transform implementation to reduce memory requirements.

st_example.m Produces

‘Stockwell Transform’ results by generating test signals and their Stockwell

transforms.

Support .m files

and images (including Wavelet library written by Miki Lustig)