Figure 1 - Brusca & Brusca 1990 [http://www.manandmollusc.net/cepheye.html]

Most image technologies focus on the human visual system, and engineers have become accustomed to the red-green-blue or cyan-magenta-yellow trichromatic mantra. The animal kingdom looks beyond the human visual range. While the evolution of animal vision can be interesting, it is too easy to get ensnared in the debate. Instead, the physiology and perception are less controversial and relate more to modern image systems and engineering.

Many living organisms can perceive light and react to changes in light stimulus. Simple bacteria and algae have light receptors that can harness light energy. Multicellular organisms like worms and plants also have light receptors. Yet, none of these organisms can perceive an image even though three groups of higher animals have their own flavors of vision organs. Mollusks, arthropods, and chordates are the classification phyla that have image forming eyes.

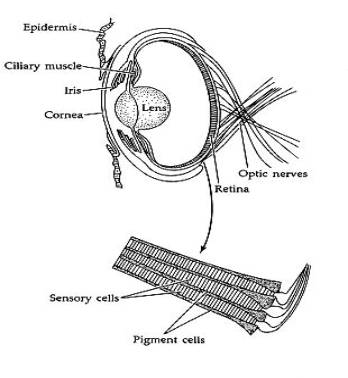

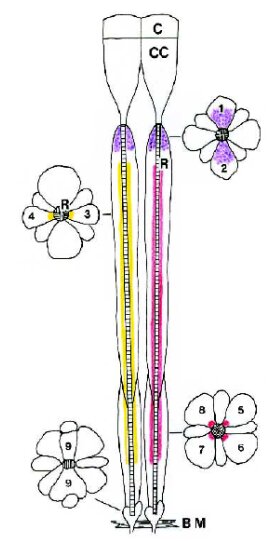

Compared to the two other phyla, mollusks are not well studied. Octopi, squid, slugs and snails are all members of this phylum. Squid and octopi are more specifically cephalopods. Their eyes are similar to human eyes, and they use a lens to focus images onto a retina. The image does not have to pass through nerve bundles between reaching the light sensitive sensitive cells. Light first hits the photoreceptors and is converted to nerve signals.

Figure 1 - Brusca & Brusca 1990

[http://www.manandmollusc.net/cepheye.html]

Arthropods include insects and spiders. These creatures use a compound eye composed of small units called ommatidia. These ommatidia have about 8 cells to detect various wavelengths of light. Of these, there are five types of receptor sensitivities. These receptors can perceive ultraviolet and polarized light, but they are quite short-sighted and are unable to focus on distant objects.

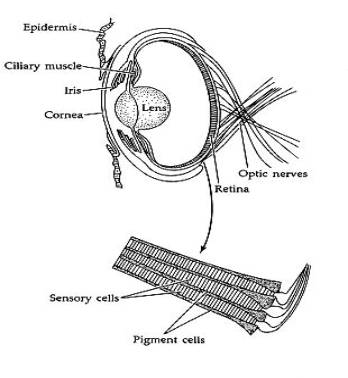

Figure 2 - A Tabanid Fly drawn in Hooke's

1665 Micrographia which shows the different densities of

ommatidia (Goldsmith, 1990). The higher densities will enable the fly

to see finer resolution and detail.

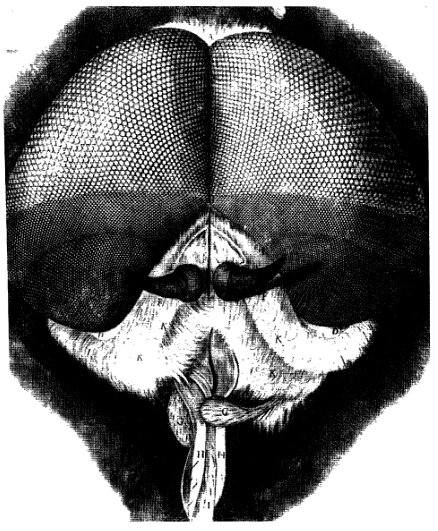

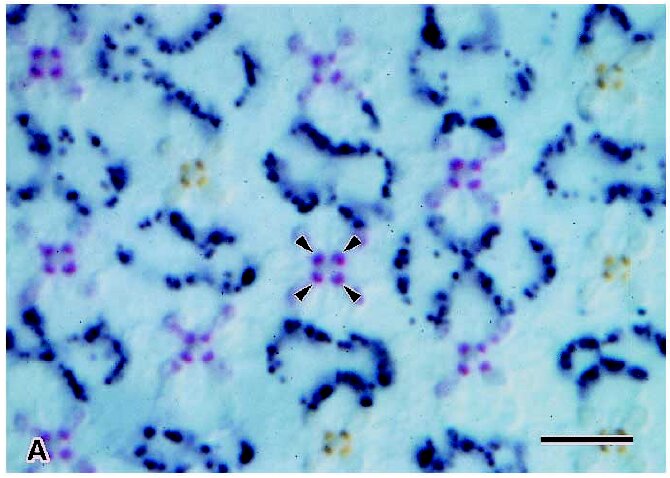

Figure 3 - Japanese Yellow

Swallowtail Butterfly (Papilio xuthus). Light is being

transmitted through the eye, showing the differing pigments of each

ommatidia (Arikawa, 1997). Horizontal distance from the rightmost

arrows to the next arrow is about 200 um.

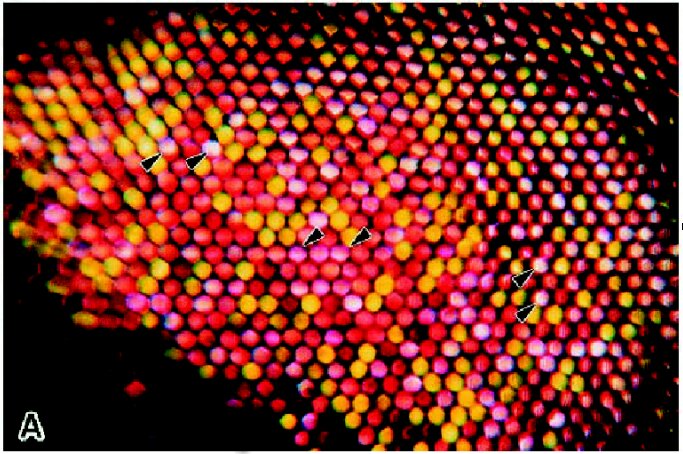

Figure 4 - An ommatidia from

P. xuthus. There are three visually distinguishable types of

ommatidia in the Hapanese Yellow Swallowtail Butterfly. They have

different sets of pigments, some of which can be better observed under

ultraviolet light. In the center of each ommatidia is an optical

waveguide which carries light to the eight receptor cells surrounding

the waveguide (Arikawa, 1997).

Figure 5 - A cross-section of a set

of ommatidia (P. xuthus). The arrows point to pigments found

in four cells of one ommatidia. The yellow-red ratio is 1:3. The

scale bar is 1 um (Arikawa 1997).

There are other methods to determine what an animal can see. So far, the micrographs have show what can be observed passively with ultraviolet and visible light microscopy. Electron microscopy reveals a bit more detail about the structure within each ommatidia cell. One technique is to isolate the photoreceptor, stimulate it with various wavelengths of light, and measure the electricial response. These techniques do not help if the animal's nervous system combines all the photoreceptor signals, masking all the color information.

More difficult behavior experiments reveal more about the internal perception of the image. One study on hooded rats uses classical conditioning techniques from psychology to study contrast sensitivity.

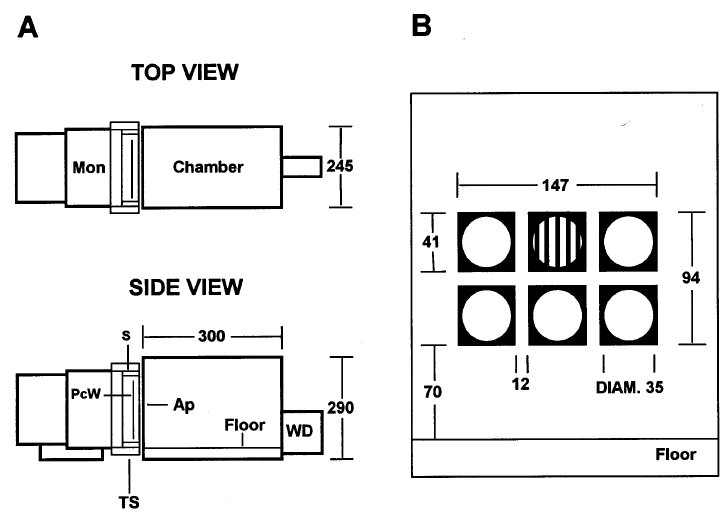

Figure 6 - Apparatus to condition and

test hooded rats (Keller, 2000). A 6-bit video display with a

infrared screen is used to allow the rats to pick the sinusoid from

five patches of grey. To train the rats, the experiment reduces the

amount of water available to the rats and uses operant conditioning

with water as a reward. Then the experimenters can vary the sinusoid

pattern and the grey patches to find the limits of the rat's visual

system.

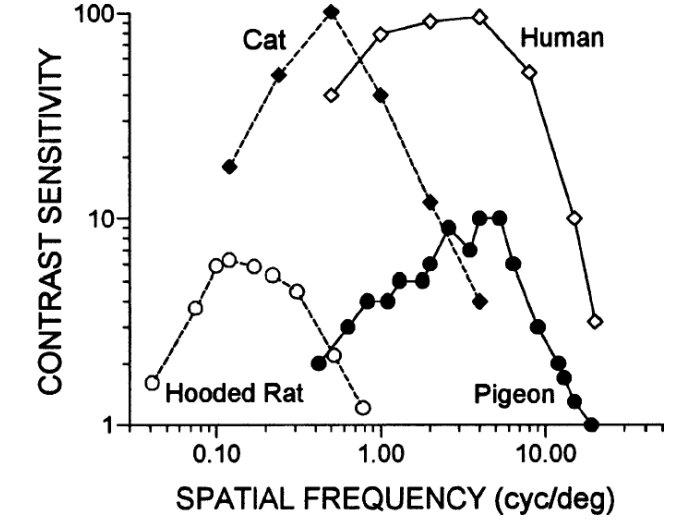

Figure 7 - The contrast sensitivity

function describes how poor the contrast can become and still be

perceptible. As the contrast sensitivity value rises, the lower the

contrast becomes. Combining the experimental data with data for cats,

pigeons, and humans, the hooded rat has comparatively poor eyesight

that may still be useful for medical studies.

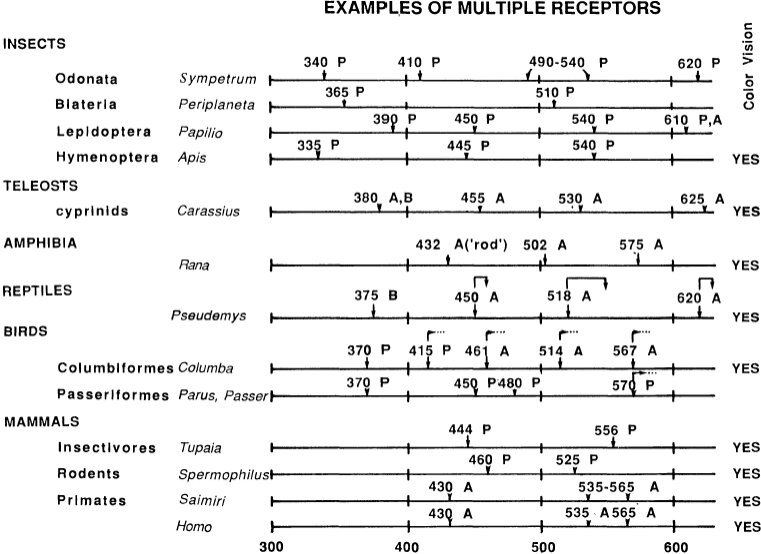

Figure 8 - Insects, fish, amphibians,

reptiles, birds, and mammals have varying numbers of photoreceptor

types (Goldsmith, 1990). Color vision requires at least two different

photoreceptors. Each receptor labeled with an A has been found by

examining absorbtion of the photopigment. The P labeled receptors

have been examined physiologically, and the B label denotes the

results from behavioral studies.

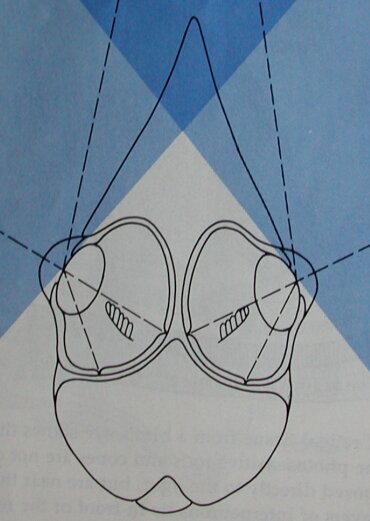

Figure 9 - Birds have eyes which are

quite different from those of primates. Some birds, like the barn

swallow shown here, have multiple foveas. Notice how the eyes are

quite large and are unable to move in their sockets. Thus, some birds

have wide peripheral vision to better detect predators. One example,

the American Woodcock, has a 360 degree field of view (Waldvogel, 1990).

In terms of the diversity of eyes and vision, birds are quite amazing. While birds have a structure within their eye called a pecten whose purpose is not clear, they are capable of seeing ultraviolet and polarized light with about four classes of cones. Their cone cells have oil droplets to help distinguish colors. Moreover, they have a higher flicker-fusion frequency, 100 Hz compared to 60 Hz for humans.

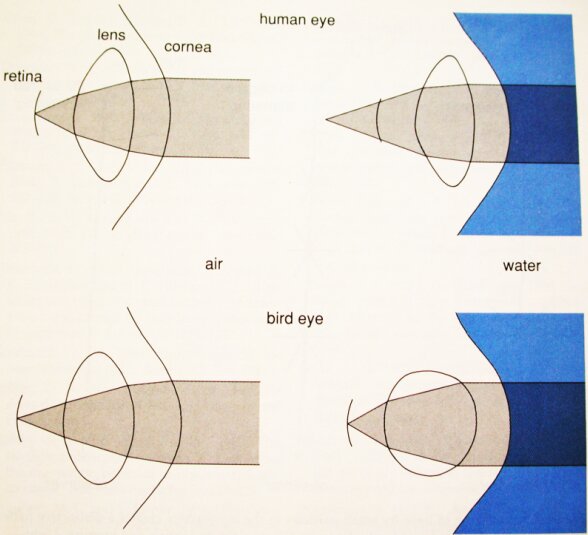

Figure 10 - Cormorant, ducks, and

pelicans need to be able to see underwater to find food. Since the

air-cornea transition provides most of the refractive power, entering

the water blurs the image at the retina since the water-cornea

refractive index is not as great. Water birds have specialized

muscles which alter the curvature of the eye to bring the image into

focus (Waldvogel, 1990).

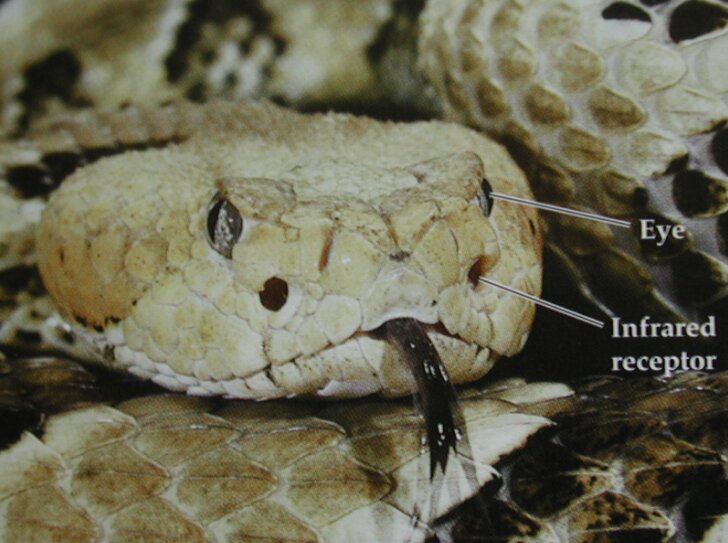

Figure 11 - Snakes have infrared heat

sensors which can perceive a mouse from one meter away.